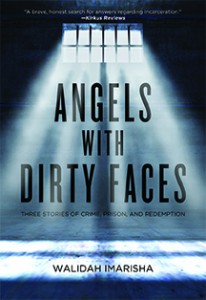

An excerpt from Walidah Imarisha’s ANGELS WITH DIRTY FACES

Here is a taste of Walidah Imarisha’s powerful new book Angels with Dirty Faces: Three Stories of Crime, Prison, and Redemption. You can read blurbs and a description, and order it, here

THROUGH THE GATES

“Ma’am, you’re going to have to check the underwire from your bra, or I’m not letting you in.”

She was a squat woman, bleached blonde wisps leaking out from her California Department of Corrections baseball hat. The mud brown uniform drew color from her face. In the unforgiving fluorescent lighting of the prison processing center, her features bled away, leaving only razor-edged eyes that bored into me, a mouth twisted with impatience.

The people waiting behind me in line, shoes and belts in hand, shifted irritably. I understood. We had all been on our feet for an hour and a half, up early enough to see the sun crack dawn over the lonely highway that, for us, dead-ended at a wall wrapped in concertina wire.

The people waiting behind me in line, shoes and belts in hand, shifted irritably. I understood. We had all been on our feet for an hour and a half, up early enough to see the sun crack dawn over the lonely highway that, for us, dead-ended at a wall wrapped in concertina wire.

In the bathroom ten minutes earlier as I hurried into a stall, I passed two women who had the movements of birds, faces heavy with makeup too hastily applied. Using the box cutter with the chipped orange handle given to me by the dour-faced guard, I ripped the seams out of my new black bra, the metal skeleton underneath as exposed as I felt. Meanwhile, the women preened in front of the warped bathroom mirror, one reapplying the dark stain of lipstick every few minutes. The other spoke of her man’s sentence as though it was a communal one they shared: “Girl, we only have 148 days left!” One woman, red-faced from her obvious hangover, laughed too loudly as her friend pointed to the hickie on the side of her neck. She murmured an embarrassed “thank you” and re-adjusted her collar to cover it.

I took in the processing room that never had enough chairs as I walked back towards the counter after the dissection of my bra. White faces dotted the institutional green. Even when it wasn’t their first visit, they always looked like it was. Most faces, however, reflected me back as I met eyes briefly: Black and brown, female. Tired. No men by themselves; only women alone, shifting on swollen ankles they had spent all week on. Many were mothers of the men warehoused here. On their faces was stamped the dogged resignation that comes from going to see your child week in and week out in a place surrounded by razor wire.

Some waiting were like the young woman in line next to me. Her carefully ironed shirt, laid out lovingly the night before, was now creased like the frown on her face as she tried to manage three wildas- weeds children, who shot questions about seeing daddy in rapid fire succession. The wide-faced baby in her arms shifted fitfully as the mother separated out the six diapers and two clear baby bottles allowed in.

Two bright-faced and dark-skinned boys tumbled past me, giggles streaming in their wake. Before their mothers had a chance to rope them back under control, one of the guards behind the processing desk boomed out, “No running in the waiting area!” The boys’ faces froze more than their bodies—eight-year-old bodies that would soon grow into young Black men bodies: dangerous property, to be handled only by professionals.

As an anti-prison organizer, my work takes me behind the walls, into cages where dignity is stripped and humanity denied, where rehabilitation is nonexistent and abuse is a daily practice. I have spent years visiting political prisoners, which this country denies having. Most of them are from the hopeful, chaotic, and turbulent 1960s and 1970s, when they believed revolution was a single breath away. Now they strain to draw each lungful in the stifling atmosphere of incarceration. Many of them have spent more years in prison than I have on this planet. I have been to the white-hot hell of Texas’s death row, and to the stainless steel brutality of Pennsylvania’s most infamous restricted housing unit. I have gone behind the walls, and I have the heartbreaking privilege to walk out of them every time.

That day’s prison in California looked like so many of the newer institutions: sprawling three-story concrete buildings, windows like slitted eyes squinting in the harsh sunlight. All new prisons look the same from the outside. And thanks to the prison-building boom in the 1980s and 1990s, almost all prisons are relatively new.

California prisons spread faster than a forest fire during a drought and became a symbol for prison growth across the country. 1852 marked the first California state prison, San Quentin. In the first hundred years of California penal institutions, nine new prisons were constructed. That state now operates thirty-three major adult prisons, eight juvenile facilities, and fifty-seven smaller prisons and camps, the majority of which have been built since 1984. The prison-building brushfire of the 1980s often relied on the same corporations and the same plans to build institutions quickly, quietly, and profitably. The corporations profited in dollars, and the state profited from the control of potentially rebellious bodies. There wasn’t time for creativity to grow in the shadow of gun turrets.

Now over 2.3 million are incarcerated across this country. One in one hundred adults are living behind bars, according to the Pew Charitable Trusts, and over seven million are in prison or on parole. This means one in thirty-one adults is under some form of state control or supervision, by far the highest rate in the world. American prisons account fully for one-quarter of the entire world prison population. Is this the “number one” people are always shouting about?

At the California prison where I was, there had been an attempt at beautification. Art pieces decorated the sterile visiting room, including a piece from my adopted brother, all flames and burnt black tree limbs. A garden was planted along the walkway to the visiting building. The inmates tended it. It was, my adopted brother told me, a coveted job, because you got to be outside, working with your hands, instead of washing someone’s dirty underwear or scraping meatloaf off 3,769 plates each dinner service. The prison’s designed capacity was seventeen hundred, but three times as many people are crammed in: 7,538 feet in shoes three sizes too small. This meant triple bunking: three prisoners lived in a cell designed for one. The gym was no longer used to release frustration; it was used as dormitory-style sleeping, where two hundred people lived on top of each other. Fifty-four people shared one toilet.

This is not unique to this prison. The majority of prisons across the country are filled until the seams are bursting, but California is an extreme case. The entire system warehouses almost double the number of people it was designed to hold, and the federal government has been forced to intervene. In May 2011, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld a lower court’s ruling: California’s prison system violated the Eighth Amendment, the prohibition of cruel and unusual punishment, though not so unusual in this nation. The Supreme Court ruled the state must parole or transfer thirty thousand prisoners in the next two years.

Thirty thousand: everyone with a loved one in California began dreaming it would be them. One in five: much better odds than the lottery. We were so busy whooping with cries of celebration, the second word of the ruling was drowned out: transfer. California argued the whole time that it could solve the overcrowding issue by new construction (during an economic collapse) or by transferring prisoners to be held in other states’ prisons. Ultimately they only had the second option. They brokered deals; they sent prisoners to Texas, Arkansas, Missouri. The State of California will still continue to pay for these prisoners, but technically the California prisoner population will be reduced—for now. Yet this is only a stopgap measure.

This is not how we stop the hemorrhaging.

.

.