Arm the Spirit! An interview with Diana Block

It’s a busy month for AK’s intrepid publicist (um, me)—March marks the release of four amazing new titles, all of them fantastic reads, all of which you should go out and buy or ask your local library to stock! It never ceases to amaze me how different the titles we publish are … and at the same time, each one has a relevance and significance for anarchist and anti-authoritarian politics in its own way. David Berry’s History of the French Anarchist Movement is a solid, scholarly investigation of the compromises we make in the name of dismantling capitalism, viewed through the lens of early twentieth-century anarchist praxis in France. Michael Schmidt and Lucien van der Walt’s Black Flame is a remarkable contribution to the debates surrounding the class politics of the anarchist tradition, both as a historical movement and as a living, breathing, acting praxis in our daily lives. Tennessee Reed’s memoir, Spell Albuquerque, is a stunning indictment of racism and prejudice in the public school system, and a testament to the great lengths that spirit and perseverance can carry us in the face of adversity. But the one that stands out for me the most right now is Diana Block’s memoir Arm the Spirit.

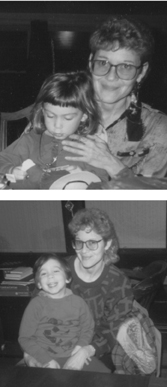

Diana’s book details the years she spent underground, having been forced to flee Los Angeles in the late 1970s as a result of her activities on behalf of the fight for Puerto Rican and Black liberation. Reading it for the first time right before its release, I think I was expecting a sort of political treatise, an indictment of the system that forced Diana and her companions underground fearing for their safety and their liberty, and not a lot else. What I found was much, much more than that—Diana’s book is truly a blending of the personal and the political. Her account of raising two children who didn’t know their mother’s real name, of having to tell her kids that their grandparents were dead or risk giving away her hidden identity, of the toll that life underground took on her relationship with her partner, and of the choice to marry that partner right before resurfacing, despite her lifelong commitment to resisting social institutions and the strictures of church and state, is nothing short of captivating. I’m recommending it to all of the women (and men) I know who are constantly engaged in the struggle between their lifelong commitment to activism and the societal pressure to settle down and raise a family. And sending a copy to my mom!

In the meantime, while you’re waiting for your very own copy to arrive, check out the brief interview I conducted with Diana about the book, and about her experiences. And be sure to check out her website (http://www.armthespirit.com) for her tour schedule—she’ll be all over the Bay Area and along the East Coast in the coming months to promote the book!

* * *

AK: Hey Diana, thanks for taking the time to answer a few questions for Revolution By the Book! Your new memoir, Arm the Spirit: A Woman’s Journey Underground and Back appears this month from AK Press, and so far the response has been fantastic! Can you tell our readers a little bit about the book?

DB: The book is the story of the thirteen years I spent underground in the eighties and nineties as part of a collective doing solidarity work with the Puerto Rican independence and Black liberation movements. The book also examines my history during the seventies, with glimpses back to my childhood, to explain why I decided to take the huge step to go underground. The book comes full circle when I return to public life in 1994 and resume political activity in the Bay Area. Of course, there is a lot of personal story in there too—my coming out as a lesbian in 1973, my decision nine years later to become involved with my life partner Claude, and our parenting of two children while underground. I won’t give away anything more.

AK: It must be difficult to reflect back on a decade spent hiding your real identity and constantly fearing that people would find out who you really were—can you talk a little about what motivated you to write the memoir, and about your experience of going back and revisiting those painful times?

DB: I needed to write the memoir. For me it was an essential part of processing the experience and reflecting on my political history and its meaning. I also hoped that sharing my story would be helpful to future generations of activists. I started to think about writing a memoir as soon as I returned in 1994, but there was just too much going on in my life for me to have the time and energy to write a book at that point. When I finally was able to carve out the space to write, the process of delving into my past and figuring out how to express it on paper enabled me to understand my history in new ways.

DB: I needed to write the memoir. For me it was an essential part of processing the experience and reflecting on my political history and its meaning. I also hoped that sharing my story would be helpful to future generations of activists. I started to think about writing a memoir as soon as I returned in 1994, but there was just too much going on in my life for me to have the time and energy to write a book at that point. When I finally was able to carve out the space to write, the process of delving into my past and figuring out how to express it on paper enabled me to understand my history in new ways.

AK: Tell me specifically about the process of reintegrating back into everyday society after resurfacing from your time underground. That must be a uniquely moving and, at the same time, disorienting experience. How did that happen?

DB: This is a big question and I take several chapters to describe what this was like. Of course, it was an amazing relief to be able to reconnect with friends, family and political associates again and to no longer worry about being caught by the FBI. But the most liberating thing for me was that I could stop hiding my core identity—my political beliefs and my commitment to fundamental social change—and begin to figure out what type of political work I could take up in this era of my life.

AK: Is there any special wisdom you’re trying to impart with this book? Or, maybe a better way to put it: what are the lessons that a new generation of revolutionaries stand to learn from hearing your story?

DB: I don’t see the book as offering easy answers or recipes. My hope is that activists/revolutionaries who read it will think about, discuss, and analyze the different things we went through and figure out what is relevant in all of this for them. And that will certainly mean different things for different people. Our political history was rooted in our commitment as white people to solidarity with Third World struggles around the world and inside this country. That commitment will take different forms today but I think solidarity is still critical for white people who want to make social change. Also, for people who live in America, we definitely need to situate our work in relationship to the efforts of people around the globe who are fighting imperialism or we cannot expect to achieve very much. The title of the book also encapsulates something of what I want to impart—people dedicated to making change need to arm their spirits—creatively, theoretically, imaginatively—in order to build and sustain a movement that is capable of transforming the imperialist system that currently deforms the world.

AK: Has your family read the book? How have they reacted to your decision to tell the story of your life underground?

DB: Yes, my family and the collective that I was part of underground have all read the book. They have been supportive of my decision and helped with the book in many different ways. Yet, I know that each of them has their own, distinct perspective on our shared history and I tried not to speak for them in the memoir or misrepresent their experiences.

AK: You and I have talked a lot about how to best present the book to the reading public, and you’ve stressed the fact that your story is written from a specifically feminine perspective, and you’ve even suggested that what you’re doing in this book is bringing a very female dimension to a field of discourse normally dominated by very heroic, very male voices. Can you talk a little bit about that?

DB: My story is told from a feminist perspective, because that is my standpoint in life. Without getting into a complicated definition of feminism, I would say that the subject of clandestine activity and armed resistance has primarily been defined and interpreted by men. This leads, in many cases, to a narration that emphasizes the macho, military and heroic aspects and downplays not only the personal and emotional aspects of the experience but also the many contradictions and challenges of work in this arena. It was important to me, throughout the book, to offer not only my perspective as a woman but to also reflect on the experiences of women around the world who have taken up armed resistance as part of their peoples struggles for liberation. In far too many cases, after a military victory was won women as a whole were stripped of all the power they had achieved during the armed struggle which raises many difficult questions about how to insure women’s true empowerment through all stages of social transformation.

AK: Anything else you want to add?

DB: I am really looking forward to engagement from readers with the ideas presented in the book. The events and readings in the next period are an important part of the book process for me and I really hope that people will take the time to give me feedback in person or by emailing me at Diana@armthespirit.com.