Italian Anarchism, 1864–1892 — Book Excerpt

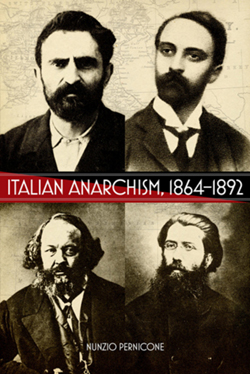

AK Press is proud to announce its new edition of Nunzio Pernicone’s Italian Anarchism, 1864–1892. The late, great Paul Avrich said of the book “Pernicone writes with an eye for the apt quotation and telling detail, and has organized a complex subject into a coherent and effective narrative.” Pernicone’s “effective narrative” indeed drives this book, taking the reader from Bakunin’s arrival in Italy in1864, to the rise of the First International, from anarchist insurrection and State repression, to crisis, defection, infighting, and―with the help of Errico Malatesta―gradual regrowth. Errico Malatesta plays a prominent role throughout, but is in good company with such heroic figures as Michael Bakunin, Carlo Cafiero, Luigi Galeani, Saverio Merlino, and Andrea Costa.

AK Press is proud to announce its new edition of Nunzio Pernicone’s Italian Anarchism, 1864–1892. The late, great Paul Avrich said of the book “Pernicone writes with an eye for the apt quotation and telling detail, and has organized a complex subject into a coherent and effective narrative.” Pernicone’s “effective narrative” indeed drives this book, taking the reader from Bakunin’s arrival in Italy in1864, to the rise of the First International, from anarchist insurrection and State repression, to crisis, defection, infighting, and―with the help of Errico Malatesta―gradual regrowth. Errico Malatesta plays a prominent role throughout, but is in good company with such heroic figures as Michael Bakunin, Carlo Cafiero, Luigi Galeani, Saverio Merlino, and Andrea Costa.

The following excerpt, taken from Chapter Twelve, covers the state of the movement from 1889 to 1891. It illustrates the tensions within anarchist camps that have, sadly, always existed, but shows the strong desire, advocated here by Malatesta, to return to the masses and a pragmatic revolutionary politics. Contemporary followers of the anarchist movement will find Malatesta’s concerns with marginalization all too familiar. Read the rest of the book for a full picture of a movement as it grapples with the complexities of anarchist thought and action.

—–

The principle of association was central to Malatesta’s revolutionary ideology. He realized that advocating association would alarm the anti-organizationists and individualists, but he knew that the movement’s decline could not be reversed if it remained atomized and isolated. He rejected the anti-organizationists’ belief that only a completely amorphous movement could guarantee the liberty and free initiative of the individual. Such notions negated the anarchist program. Association was the natural form of society; it did not threaten the individual, rather it provided the best guarantee of freedom, justice, and equality. Association was the sine qua non of anarchy itself.

Before anarchists could associate, however, they would have to cease squabbling over ideology. Already apparent in his writings of 1884, Malatesta’s relativism in matters of speculative theory had become stronger after his stay in Argentina and his experience mediating between rival anarchist tendencies. Utopian blueprints, a priori assumptions, abstract and rigid formulas—Malatesta eschewed them all. He believed it a waste of time to battle over whether postrevolutionary society would be collectivist, communist, or some other preconceived system. Unanimity in matters of theory was not necessary before acting. Theoretical differences should be subordinated to the immediate demands of the common struggle against the state and bourgeois society, and in his program of 1889 Malatesta appealed to anarchists of every tendency to abandon their ideological exclusivism.

As a relativist, Malatesta stood apart from the great majority of his Italian comrades in 1889–1890, for whom anarchist communism had become dogma. Although convinced that anarchist communism was the form of societal organization that would best assure equality and social justice, Malatesta—until 1900 at least—preferred to use the generic term anarchist socialist to describe himself. Communism was not an object of blind faith for Malatesta, and he rejected the fatalistic assumptions about communism that most Italian and French anarchists derived from Kropotkin. Positing free will (volontà) as the driving force in human development, Malatesta maintained that “the modes and the particulars of associations and agreements, of the organizations of work and social life, will not be uniform, nor can they as yet be foreseen or determined.” The nature of society after the revolution would be determined spontaneously and harmoniously over time by the “free wills of all.” Urging his comrades to stop arguing over hypotheses, Malatesta recommended a conciliatory alternative: “Let us hold to basic principles and strive to teach these to the masses so that they, too, when the hour comes, will not quarrel over a phrase or a detail.”

The association principle in matters of social organization, and relativism in questions of speculative theory, Malatesta hoped, would cure the internal dissension that kept the anarchist movement divided and weak. Equally important to the task Malatesta envisaged was bridging the gap between the anarchists and the masses. Anarchists could not hope to convert the masses to their creed if they remained aloof from them. One of the few anarchists to acknowledge the serious extent to which the movement had lost contact with the day-to-day struggles of the working class, Malatesta attributed the problem to the sectarian and isolationist tendencies that had developed during and after the First International. To remedy the situation, Malatesta called upon the anarchists to “return among the people,” utilizing propaganda of the word and deed to arouse the spirit of revolt against property, government, and religion.

Malatesta’s program of 1889 called for almost every means of direct action except terrorism. Aware that Europe had entered a new era, Malatesta concluded that the anarchists should abandon some of their old tactics and adopt some new ones. The classic armed band, he now believed, was ill suited for contemporary conditions because the many requirements needed for guerrilla action were too difficult to fulfill. He urged, therefore, that the anarchists substitute “the free, spontaneous, incessant action of individuals and groups” for the “classic band.” One form of group action that Malatesta strongly endorsed was the strike. The critical attitude toward strikes he had expressed in the 1870s had already changed to favor by 1884, and did so even more after his Argentine experience. But it was the wave of worker agitation sweeping Europe and America in the late 1880s, above all, that caused Malatesta to substantially rethink his position regarding strikes. Anarchists in the past, he now acknowledged, had been mistaken when they rejected the strike as an economic weapon and ignored its importance as a vehicle for moral revolt. They should, therefore, seize every occasion to stimulate and participate in strikes, as a means to resume contact with the masses and orient them toward revolution. He declared in L’Associazione:

The masses arrive at great vindications by means of small protests and small revolts. Let us join them and spur them forward. Spirited men throughout Europe are at this moment disposed toward great strikes of agricultural or industrial workers that encompass vast regions and numerous associations. Therefore, let us provoke and organize as many strikes as possible; let us ensure that strikes become contagious, that when one explodes it extends quickly to ten or a hundred different trades, in ten or a hundred towns.

Indeed, every strike has its revolutionary characteristic; every strike finds energetic men to punish the bosses and, above all, to attack property and to show the strikers that it is easier to take than to ask.

Malatesta had been particularly impressed with the London dockworkers’ strike of September 1889. He believed that, had labor leaders encouraged the workers to expand their stoppage into a general strike, conditions in London would have become critical for the bourgeoisie—at which point the people, realizing their opportunity, might have rebelled and the revolution ensued. Malatesta was careful, however, to distinguish between a general strike and a general uprising. Unlike the syndicalists who soon became prominent in the French anarchist movement, Malatesta never considered the general strike synonymous with the revolution. “The strike,” he cautioned, “must not be a war of folded arms”—an allusion to the syndicalists’ notion that capitalism could be brought down if all the workers simply halted production. The general strike, according to Malatesta, was merely an excellent opportunity to initiate the revolution by leading the workers in armed attack against the state and in expropriation of the bourgeoisie.

The breadth and intensity of workers’ agitation in 1889 convinced Malatesta that “a great revolution is approaching, perhaps it is imminent.” He firmly disavowed, however, the notion that “the revolution will come by itself, like manna from heaven, and that we have only to fold our arms to assist impassively in the collapse of the old society.” Still much closer to Bakunin than Kropotkin in his conception of revolutionary strategy, Malatesta believed that although only the masses could make the revolution, they needed the guidance of a vanguard anarchist party. For only the anarchists, who harbored no secret desire for power, could arouse the masses to full consciousness of their might and spur them to destroy the state and every other obstacle blocking emancipation. And only the anarchists could be relied upon to resist the formation of new governments that would impose their will upon the masses, arrest and divert the course of the revolution, and prevent the evolution of a libertarian society.

In order to fulfill the movement’s “great mission,” Malatesta recommended the formation of an international revolutionary-anarchist-socialist party. By party he meant “the totality of all who embrace the program, who advocate its triumph and who consider themselves bound not to do anything opposed to it.” This party would reconcile the free initiative of individuals and groups, and the free development of all faculties and wills, with the unity of action and the discipline required for action. The modes by which cooperation and solidarity were to be achieved would vary considerably, depending upon local conditions and the needs of the struggle. Groups devoted to action might have to operate on a clandestine basis, divulging their identity only to trusted comrades or perhaps retaining complete secrecy. Others capable of operating openly might organize themselves into federations. Ultimately, the anarchists of different regions and countries would establish close relations with one another so that agreement could be reached over common goals.

Malatesta’s program of 1889–1890 represented a radical alternative to the modes of thinking and behavior that had come to predominate in anarchist circles by the late 1880s. Nothing less than a total transformation of the movement could realize his vision of the anarchists as a vanguard party devoted to revolutionary activity. Malatesta did not believe he was asking the impossible. Whether anarchism would meet Malatesta’s challenge and develop into a serious party of action on the Italian left or continue gravitating toward marginalization was the central issue confronting the movement over the next three years.