Free Comrades — Book Excerpt

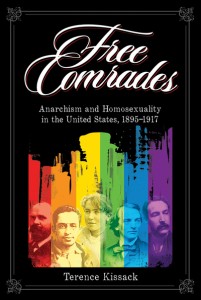

Revolution by the Book will periodically post excerpts from new (and older) AK Press books. This one consists of two, brief selections from Free Comrades: Anarchism and Homosexuality in the United States by Terence Kissack (AK Press, 2008). The first outlines Terence’s reasons for writing the book. The

second gives you a taste of how he went about doing so.

Enjoy!

* * *

Selection from pages 7–8:

While there has been some work done on the sexual politics of a number of European anarchists, historians of American anarchism have not fully appreciated the importance of the anarchists’ politics of homosexuality. This is not to say that  the phenomenon has gone completely unnoticed. Several studies of anarchism, in particular biographies of Emma Goldman, have noted that the anarchists spoke out against the unjust treatment of gay men and lesbians. For the most

the phenomenon has gone completely unnoticed. Several studies of anarchism, in particular biographies of Emma Goldman, have noted that the anarchists spoke out against the unjust treatment of gay men and lesbians. For the most part, however, these studies do not examine the homosexual politics of Goldman and her comrades in any depth. More often than not, the anarchist discussion of homosexuality is noted briefly, just another example of anarchists defending individual rights. Of course, any study of anarchist sexual politics must begin with this basic truth, but it cannot end there. This book gives greater texture and richness to the largely anecdotal evidence that currently constitutes our understanding of the relationship between American anarchism and the politics of homosexuality. In the pages that follow, I examine why the anarchists began to address the social, ethical, and cultural place of homosexuality; how they went about doing so; what discourses―including sexology and literature―shaped their thinking on the matter; and to the extent we can know, what effect these efforts had.

Historians and political scientists working in the field of American gay and lesbian studies have also overlooked the work of the anarchist sex radicals. This is largely because the anarchists do not fit into the models of gay and lesbian identity and politics that have come to dominate historical and political discourse in the post-World War II era. Anarchists and the politics of homosexuality they produced are not easily assimilated into current social, cultural, and political categories. They were not “gay activists,” nor did they operate within the bounds of liberal, civil rights discourse.

Those who study the history of the politics of homosexuality have tended to focus on those organizations and individuals who share the largely liberal, reformist outlook and tactics of post-World War II gay and lesbian politics. Hirschfeld, Ulrichs, and other European activists, for example, are easily assimilated into modern narratives of political progress and community-building, and their politics fit within the context of contemporary strategies for social change. Anarchists did not seek to reform legal codes, nor did they lobby politicians in order to get the police to stop raiding the clubs and bars frequented by homosexuals. Their vision for change was something more fundamental―a radical alternative to the principles of the established rules of the American social order. The sexual politics of anarchist sex radicals was embedded in the larger political discourse of anarchism―they wrote as anarchists, not as homosexual rights activists. This is not a study of gay and lesbian anarchists, rather it is an examination of what anarchist sex radicals had to say about the legal, cultural, and social status of same-sex love.

That historians have not fully documented the work of anarchists in relation to this issue is also due to the way that the Left developed in the United States. From the late-nineteenth century through the early decades of the twentieth century, anarchism was a vital force in the United States. Thousands were active in organizations that ranged from experimental schools to labor unions; anarchist journals, including Liberty and Mother Earth, enjoyed considerable readership; and thousands attended lectures by noted anarchists. But the anarchist movement in the United States never recovered from the suppression it endured during and immediately after World War I, when most of its journals were shut down and several of its most important activists were imprisoned and deported under the Sedition Act of 1918. In the 1920s and 1930s, what remained of the movement was overshadowed and dogged by the ascendant Communist Party (CP). The CP came to dominate the Left in a way that excluded and marginalized the ideas and perspectives of the anarchists. For many Americans the history of the Left is synonymous with the history of the CP or its various Marxist-Leninist critics. There is little room in the American historical imagination for libertarian socialism.

Selection from pages 143–144

Goldman delivered her lectures on the topic of same-sex eroticism to a broad audience. Unlike most presentations by physicians and other professionals, Goldman’s talks were open to the public and held in accessible venues. Occasionally, there were other public lectures on homosexuality, such as those given by Edith Ellis, the wife of Havelock Ellis, who visited Chicago in 1915, but they were rare. Lecturers like Ellis usually spoke only in major cities, and their tours were limited in scope and reach. Goldman’s lectures were advertised in Mother Earth and the non-anarchist press, and she spoke in large and small cities across the nation, addressing audiences in New York; Chicago; St. Louis, Washington, D.C.; Portland; Denver; Lincoln, Nebraska; Butte, Montana; San Francisco; San Diego; and others. She spoke in a wide variety of venues: from local labor halls to Carnegie Hall. Goldman estimated that 50,000 to 75,000 people a year heard her speak. Though not every listener came to her presentations on homosexuality, the numbers of people who heard Goldman speak on the topic of same-sex love were significantly higher than any other of her contemporaries.

Goldman’s lectures on homosexuality drew large and responsive crowds. On the night of a presentation in Chicago in 1915, Goldman feared the worst as the evening “was visited by a perfect cloudburst,” an event known to ruin many a public gathering. Nonetheless, she has happy to report that “a large and representative audience braved the storm” to hear her speak. In that same year, “Anna W.” reported in Mother Earth on one of the Goldman’s lectures on “homo-sexuality” that she gave in Washington, D.C. Goldman, writes Anna W., is a “sympathizer and true friend of the socially outcast,” who “in the face of strenuous general opposition to the discussion of a subject long enshrouded in mystery and persistently tabooed by all other public speakers…delivered a most illuminating lecture on homo-sexuality.” According to Anna W. a “dignified, tense, and eager audience crowded the hall to its fullest capacity.” Consumed by curiosity audience members actively sought information from Goldman. “The frankness and celerity with which they questioned and discussed were evidences of the genuine and deep interest her treatment of the subject had aroused.” Goldman was clearly responding to a thirst for public discourse on the topic.

Goldman was more forceful than other speakers in her exploration of the social, ethical, and cultural place of same-sex desire. Margaret Anderson, for example, thought Edith Ellis paled as a speaker in comparison to Goldman. Ellis’ speech did not go “quite the whole distance” and, comparing Ellis to Goldman, Anderson argued that Ellis’ stage presence did not “loom as large as some of her more ‘destructive’ contemporaries.” The reference to Goldman’s “destructive” power is a playful jab at her unmerited reputation as a bomber, and her well merited reputation as an “explosive” speaker. Ellis, on the other hand, failed to grasp the nettle. Though she cited Carpenter’s work, Ellis did not discuss “Carpenter’s social efforts in behalf of the homosexualist.” Instead of engaging in a direct political confrontation, Ellis merely pointed to the fact that not all homosexuals were to be found in insane asylums; some occupied thrones or were famous artists. But Anderson was unimpressed, “It is not enough,” she insisted, “to repeat that Shakespeare and Michael Angelo and Alexander the Great and Rosa Bonheur and Sappho were intermediaries.” Ellis, unlike Goldman did not ask the key question: “how is the science of the future to meet this issue?” According to Anderson, Ellis underestimated her audience and failed to “talk plainly.” Having heard Goldman speak on the subject, Anderson lamented that Ellis could not have emulated her more “destructive” contemporary. “I can’t help comparing [Ellis],” Anderson wrote, “with another woman whose lecture on such a subject would be big, brave, beautiful…Emma Goldman could never fail in this way.” Goldman’s political passions and her engagement with the “science of the future” led her to be more direct and confrontational in her discussion of matters others treated with kid gloves.