Defining Anarchist Art: Gleanings from a Roundtable on Realizing the Impossible

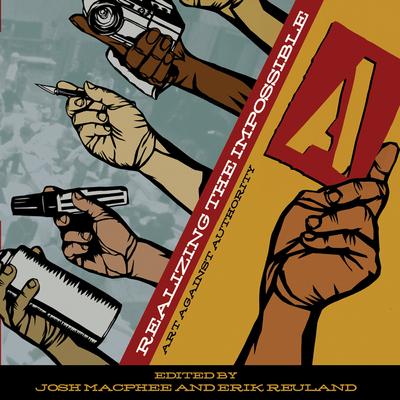

The Institute for Anarchist Studies has posted more material from their ongoing, online 2009 issue of Perspectives on Anarchist Theory. It includes two pieces about Josh Macphee and Erik Reuland’s Realizing the Impossible: Art against Authority (which AK Press published back in 2007). There’s a detailed review by Alan Moore, and a very interesting roundtable discussion about the broader questions of “anarchist art.” You can check out the entire issue here. Below is the statement Josh Macphee used to open the roundtable discussion. Highly recommended reading!

The Institute for Anarchist Studies has posted more material from their ongoing, online 2009 issue of Perspectives on Anarchist Theory. It includes two pieces about Josh Macphee and Erik Reuland’s Realizing the Impossible: Art against Authority (which AK Press published back in 2007). There’s a detailed review by Alan Moore, and a very interesting roundtable discussion about the broader questions of “anarchist art.” You can check out the entire issue here. Below is the statement Josh Macphee used to open the roundtable discussion. Highly recommended reading!

******

Josh MacPhee: We put together Realizing the Impossible because we wanted to read a book that explored the relationships between art and anarchism in a myriad of diverse ways, but it just didn’t exist. That’s often the reason people put out books, because they want to read something and they can’t find it, so they try to bridge the gap. Relationships between art and anarchism are an under-explored subject. While there are a lot of anti-authoritarians producing artwork, there’s not a lot of intellectual work theorizing how that art exists in the world, and how it’s different from what other political cultures have produced.

As with all left social movements, in anarchist activism there is an antagonism towards art as a result of the idea that social transformation comes from the difficult and tireless work of organizing and activism, and art is something that needs to be pushed to the side when “real work” needs to get done. Realizing the Impossible is a collection of writings, art, and interviews that argue against that idea, and demonstrate that cultural work is not a side show, but a main event. A look at history will show that most dramatic social transformations have had strong cultural components.

When creating art, one of the things I have always tried to ask myself is, “is this effective?” I believe it’s valuable to express myself and I think that’s why most artists create art, but if we want to claim our art and culture as somehow leaving the realm of simple self-expression and intervening into the political landscape, then we need to ask deeper questions about what our art does, who it effects, why and how.

I want to quickly bring up a couple of examples in the book that raise these questions. First, in his essay on Danish anti-authoritarian art practice, Brett Bloom introduces us to Christiania, a squatted free city on the edge of Copenhagen that has been in existence for almost 40 years. Christiania largely came into being as a result of conversations started at an art show: its actual beginnings look and seem more like an art gesture than traditional activism or organizing, and its existence has always had an extremely aesthetic component.

Another essay in the book is a critique of contemporary adbusting techniques written by Anne Elizabeth Moore. In the essay she demands that people attempting to critique corporations semiotically need to do more than create self-serving parodies of corporate logos, but dig much deeper. We need to really study and understand how corporate semiotics and branding works, and we need to build a resistance practice that we can assess is having an effect on corporations, not inadvertently supporting their world view. I think these are both good places to start a conversation about art and politics.