Signs of Change reviewed in Afterimage

A full report on this weekend’s tabling insanity is forthcoming, but one nice thing that happened for me in NYC is that I got to see (briefly) my friend Daniel Tucker (co-editor of Chronicle Books’s Farm Together Now) who passed along the text of a review he just wrote of Signs of Change for Afterimage. Thanks Daniel!

Originally Published in Afterimage Vol.38 #5, reposted from Daniel Tucker’s MiscProjects Blog

“We’re Still Here” read the large script on a mid-sized street-level billboard below a black-and-white photograph of a family staring confidently at the camera. The image was tiled and wheat-pasted in four pieces to cover a paid advertisement. This poster was not a paid ad, but an illegal public service announcement produced by the anti-gentrification activists in San Francisco’s Mission District. It signaled to all who viewed it that working-class immigrant families being priced out and evicted from the neighborhood were not leaving without a fight.

“We’re Still Here” read the large script on a mid-sized street-level billboard below a black-and-white photograph of a family staring confidently at the camera. The image was tiled and wheat-pasted in four pieces to cover a paid advertisement. This poster was not a paid ad, but an illegal public service announcement produced by the anti-gentrification activists in San Francisco’s Mission District. It signaled to all who viewed it that working-class immigrant families being priced out and evicted from the neighborhood were not leaving without a fight.

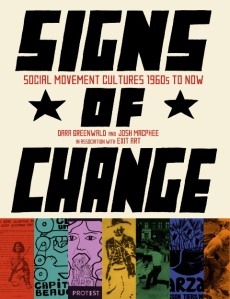

Graphics like “We’re Still Here” make up a small fraction of the catalog and recent exhibition “Signs of Change: Social Movement Cultures 1960s to Now” by Dara Greenwald and Josh MacPhee. Other movements profiled in the catalog include the Zapatistas, the United Farm Workers, the Attica Prison Rebellions, the Anti-Apartheid movement, squatters from Amsterdam to New York City, and, more recently, activism around climate change. The project is organized into seven broad thematic categories ranging from the relatively straightforward “Struggle for the Land,” which includes American Indian, Northern Irish, and Palestinian struggles, to the more abstract “Let It All Hang Out,” which encompasses 1960s and 70s countercultures like Provo, the Yippies, and more recent punk-inspired subcultures experimenting with ways to circumvent the commodification of everyday life.

“Signs of Change” was initially developed as part of the “curatorial incubation” program hosted by Exit Art, which hosted the first incarnation of the exhibit. It has since traveled to the Miller Gallery in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; the Arts Center of the Capital Region in Troy, New York; and the Feldman Gallery at the Pacific Northwest College of Art in Portland, Oregon. Viewing the materials in person was like taking a walk through the art studios and community centers of some of the twentieth century’s most inspiring “people power” moments. The beautifully designed book will bring that experience to even more people, and is much more generous with full-color reproductions, original writing, and research than most exhibition catalogs produced outside of major museums. Greenwald and MacPhee have significant experience in producing the type of culture documented in “Signs of Change.” Many of the prints, photos, and videos featured in the show were obtained through personal relationships between the curators and other artists and activists. Much of the rest of the work was borrowed from the collections of the International Institute of Social History in Amsterdam and The Center for the Study of Political Graphics in Los Angeles, which the organizers point out have been able to amass sixty-thousand postwar political posters “with minimal institutional funding . . . [and no affiliation] with any major educational or art institutions.” This independence has allowed for a more integrated relationship between the archival work and the cultural and political work being documented. Many of the pieces included in the show and book are now being collected in the new, permanent Interference Archive in Brooklyn that is administered and will be made public by Greenwald and MacPhee in the near future.

“Signs of Change” allows the reader to interpret grassroots social movements through the lens of the visual culture they produced, helping us to move beyond a focus on the spoken and written words of leaders and historians, which tend to dominate our understanding of these histories. Greenwald and MacPhee bring together images as diverse as reproductions of the three-dimensional arpillera textiles produced by Chilean women to increase awareness of repression under the Pinochet regime in the 1970s; photos of the 1978 Democracy Wall in China, adorned with posters and poems criticizing the anti-democratic policies of the Chinese Communist Party; and screen-printed posters from the Larzac community of farmers and activists in France who banded together throughout the 1970s to resist the construction of a military base. These three examples, among many others in “Signs of Change,” present a powerful—albeit fragmented—alternative narrative about the world in the 1970s. As the authors acknowledge in the catalog’s conclusion, their goal is to shine a spotlight on social movement culture; now the work of interpretation and analysis can begin to read the contradictions and connections through the merging of disparate histories.

As a contribution to art history, “Signs of Change” opens a critical dialogue about the distinction between art that is “about” politics, and art that is created within the context of political struggle and action. As a contribution to leftist history, the exhibition and book reveal the array of aesthetic and artistic strategies produced by social movements themselves, and how they can help us better assess the importance of art within politics. As a contribution to our collective human history, “Signs of Change” uses images to tell a different story about the past half-century of life, with the rise of informational capitalism, economic and cultural globalization, and constant war.