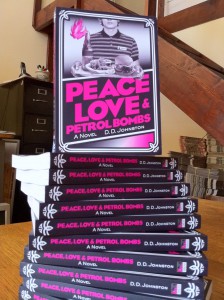

Peace, Love & Petrol Bombs has arrived in Baltimore!

Peace, Love & Petrol Bombs, D.D. Johnston’s first novel, and the second title in our new fiction series, has arrived in Baltimore! It should arrive in Oakland any day now, so capital F Friends and those of you who have preordered should be receiving it very soon! If you haven’t yet placed an order for it, don’t worry there’s still time to get it at 25% off the list price of $14.95. Just scoot on over to akpress.org and click the “Buy it now!” button!

Peace, Love & Petrol Bombs, D.D. Johnston’s first novel, and the second title in our new fiction series, has arrived in Baltimore! It should arrive in Oakland any day now, so capital F Friends and those of you who have preordered should be receiving it very soon! If you haven’t yet placed an order for it, don’t worry there’s still time to get it at 25% off the list price of $14.95. Just scoot on over to akpress.org and click the “Buy it now!” button!

In the meantime, whet your appetite with this excerpt in which our protagonist, Wayne finds himself preparing to hit the Greek streets in Black Bloc style with French anarchist, Manette.

In June 2003, Manette and I travelled from London to Thessaloniki. We arrived on a train from Belgrade, which creaked and hissed, straining to stop at the platform. Doors swung open and from different carriages a dozen people emerged into the morning heat. Two men jumped from the first carriage, laughing as they ran down the steps free of luggage. A family passed laundry bags from the train and cursed the broken handles, holding them underarm where the checked canvas had split and pots and children’s toys nosed into the sunshine.

It was cool in the station building—fans motored; a man in a long winter coat picked cigarette butts from the dark slabbed floor—but outside, Thessaloniki sweltered in the morning sunshine. Bus drivers in big sunglasses leant against their vehicles, and nine policemen loitered by a small office. The police looked up as Manette threw her rucksack into the shade, but they slumped back into conversation as she unzipped the top pocket and tugged out her guidebook.

I sighed and leant my rucksack against the wall.

“What,” she said, lifting her sunglasses onto her hairline, “you know the way?” We had slept on trains the previous two nights, and dots of stubble had reclaimed her armpits. “Fuckeeng shut up then.” Beyond the buses, through the haze, cars paused at traffic lights. Engines revved. Now and then a horn sounded. Manette folded the book, trapping the page with her finger, and then she lifted her rucksack and walked into sunshine that hurt my eyes.

“You sure?”

“You want to study the map?” She must have been exhausted; during the night, I had slept on her lap, and so I wouldn’t wake, she had cupped her hands over my ears whenever the train had roared through a tunnel.

In Platía Yardhari, the leaves of trees looked lush above the scorched yellow grass, and the smell of roasting vegetables mixed with the background pong of stalled sewage. There were posters, pasted to walls and stuck on electricity boxes, with pictures of masked figures throwing petrol bombs, and a caption in English: “We promise a warm welcome for the leaders of Europe.”

Flanked by tall pastel-coloured buildings with balconies at every floor, Odhós Egnatías is a wide road with three lanes on either side of the central reservation. We crossed to the shady side, where a waitress struggled with a parasol, and her colleague dragged metal chairs scratching across the pavement. Manette stopped to read the menu, but it was all in Greek. “Are you hungry?”

I shook my head. “Need some water but.”

“We should eat also.”

We walked in silence for a few minutes before Manette pointed ahead. “Look, Petit Fantôme, up there, that must be the…” She turned the page in her guidebook. “The Arch of Galerius.”

“Oh aye?” I dropped my rucksack in the shade and my Tshirt stuck to my skin. Around the arch’s abutments, bikes rested against green railings, and English tourists walked this way then back again, studying carvings that had softened with time. When we pulled our rucksacks on, we both laughed and grimaced as cold sweat licked the length of our backs.

We walked another fifty yards until Manette stopped at a street kiosk. She checked her guidebook and mouthed the words to herself as she stepped to the counter.

“Oríste?”

“Dhío neró parakaló,” she said, pointing.

“Dhío? You want two?” said the man, holding up two fingers.

Manette nodded and passed a note as the seller looked in his money belt for change.

On the far side of the road, audible between cars, Avril Lavigne sang on a crackly radio, as workmen fixed corrugated aluminium across the windows of Benny’s Burgers.

“Look, Benny’s,” I said.

“They fuckeeng expect us then.” When the sun hit the unpainted shutters, the metal glowed as if on fire.

From the third floor of Aristotle University there hung a black banner as big a penalty box, on which was painted “SMASH CAPITALISM” in giant white letters. Loudspeakers played “A Las Barricadas” through an open window and out into the noise of the street. But once we were on the campus, behind the Theology Department, it was all soft-paced and calm. In a square of grass criss-crossed by concrete paths, topless men finished constructing a stage, while others stretched on the yellow turf, or sipped water in the shade beneath trees, holding their arms out when ever they felt some breeze. Manette fixed on a man in a white vest, who was smoking a roll up at the entrance to the refectory. She crept up behind him, placing her hands over his eyes. “Arrette, Police!”

He kicked his chair back and spun round. “Manette, Salut! Tu va bien?”

“Ça va malaka?”

He put his arms around her waist, swinging her feet off the ground as he kissed her cheeks.

“Comment va Paris?”

“Plus de la même chose: grève à la SNCF; grève dans les écoles.”

“Sounds about right. I fuckeeng miss it, you know?”

His hands still held her shoulders with an easy intimacy that made me think that at one time they had been lovers. Eventually, Manette introduced me and Alex clasped my hand as though we were about to arm wrestle. “Come inside, please. You can leave the bags here.”

The room was empty except for a scatter of chairs and a giant drum of water. Alex pulled a can of Amstel from the drum and the water lapped the sides and the cans bobbed like rowing boats. “You want beer? They take all the refrigerators so we keep them cold like this. They take everything from this building, all the computers, everything. But in the Law Building, across there, we have Indymedia Centre, and this is also the base for the medics.”

“Wow.”

“Yes.” We sat with our beers: Manette and Alex sat on plastic chairs; I sat cross-legged on the cool tiled floor. Alex was in his mid-twenties with dark hair almost as short as his stubble. He had the build of a medium-weight boxer, but there was something quiet about the way he sat. “They learn that we will squat this building and they plan to build gates and hire private security. So we go to the Dean of Theology and we say: One way or another we occupy this building. Either you give us the keys and we stay here, look after it, and next term you still have the building; or, we fight your security, we smash our way in, we break everything, and we burn it before we leave. After this, he give us the keys. Anyway, welcome. Stinyássas. To a hot summer.” We tapped our cans together and drank. “So, how you come, by plane?”

“Nah, train. We met some comrades in Belgrade yesterday, then came down overnight.”

“Is good this way, I think. No problems at the border?”

“Nah, no search or anything.”

“And the Serbian comrades, they come also for the manifestation?”

“They cannae get visas, can they?”

“Po-po-po. This is very important. Tomorrow night—tonight is big party, we have bands playing, we drink, we have fun—but tomorrow night we make manifestation for solidarity with the sans-papier, you know?”

“That’s tomorrow night?”

“Yes, yes. Is not us who organise this, but is our friends from Athens. We make the manifestation in the suburbs, where is the homes of many Albanians and other immigrants, so is very important that we do not make the fight then. Not because we are pacifist, but because we do not want to damage the neighbourhood of our Albanian brothers and sisters, you see? Then next day we make the main manifestation, and where we find the police in the most number, there we attack. With the sticks, with the stones, and with the fire.”

In the afternoon, we explored the university and the streets outside. It was summer vacation; bushes grew unpruned and weeds squeezed between paving stones. Political slogans and posters advertising long-passed demonstrations covered the walls. The university buildings were concrete with big windows that reflected the sun, and in-between these modern blocks there were half-excavated Roman remains: the base of a column, an engraved flagstone, a knee-high wall. Near the Law Department, beneath a sunshade suspended between two trees, a man in shorts cooked stew in a big pot, and behind him two women descended a grassy slope, weaving between tents, clambering over guy ropes.

In the evening, we bought red wine and plastic cups, and we sat on the grass with Alex. On the stage, a punk band hacked through a sound check. Then they shrugged and jumped onto the grass, leaving their instruments leaning in the sunshine and the square quiet except for the hum of a Vespa. I watched the riders approach, their shirts billowing as the girl held the boy round the waist. They stopped outside the Theology Building, and everyone looked as they removed their helmets.

“Hey Stavros!”

“Alex, malaka!”

As those around me returned to their conversations, I lay on my back and let the sun shine orange through my eyelids.

I fell asleep like that, and when I woke the sun had gone and people were standing up, pointing and shouting, as a crowd—maybe fifty people—rushed past the Theology Building. They had a road sign on a metal pole, and they were whooping with wild energy.

“You are awake,” said Alex, slapping me on the back.

“Look,” said Manette. “Hristos!”

“You know these malakas?” asked Alex, rolling a cigarette.

People ran from the tents, chanting “No justice, no peace! Fight the police!” They swarmed around the steps of the Philosophy Building, and Manette held my hand as we ran towards them. She called out to Hristos, but the crowd was too loud. There was something of the medieval siege about it; the metal pole, still with the no-left-turn sign attached, was being used as a batter ing ram. It swung backwards and forwards, held by more hands than there was room for. Then the door crashed open and the crowd cheered and surged forward. I could hear smashing before we were all inside. As we ran through the corridors, a punk hit light bulbs with a stick. Someone let off a fire extinguisher. Near the front door, where a noticeboard had been ripped off the wall, a man in a black vest sprayed big letters: “We don’t forget. We don’t forgive. Carlo vive.”

We didn’t realise how many people were in the university until the immigration demo. Then they streamed from every building. There were thousands of us—four, five-thousand of us—squeezing through the university gates, hoisting flags. Some wore bandannas but most didn’t. Some had cameras swinging from their necks and others held cans of beer. Some were running at the side of the march, spray painting the wall of a church. You wanted to scramble to the highest point so you could see it all.

Then, at the crossroads, we saw riot police in the side streets. They were dressed in green uniforms and white helmets, and they held their shields to their chins. Young anarchists ran forward to throw bottles. They stood in the road, swearing and taunting, until their friends put arms round their necks and pulled them back. Sometimes, the police ran forward, shouting and gesticulating, until they were restrained by their colleagues. It was getting hotter and hotter. When the march roared as one, the noise left you feeling winded. “BATSI! GOUROUNEA! DO-LO-FONÉ! BATSI! GOUROUNEA! DO-LO-FONÉ!” Cops, Pigs, Murderers! Cops, Pigs, Murderers! Louder and louder, until you heard it with your whole body and your insides shook.

In the evening, the sun slipped behind the Theology Building, and the darkness seemed to grow out of the shadows. A smell of petrol settled over the university, and we talked so quietly you could hear the chink of empty bottles and the lawnmower buzz of cicadas. “I have heard,” said the American guy, pausing and looking behind him, “that there was a meeting in the Philosophy Building, a meeting of insurrectionists, who say they plan to kill a cop in revenge for Carlo.”

“Fuck,” said the English guy.

“This is the shit I’m talking about, man!” Welsh Rob stretched his legs out on the Labrador-coloured grass. “This is what I’m saying to you; half the people here are fucking crazy. Look,” he said, whispering now, bird-like the way he pecked around for danger, “there are guys staying here who have outstanding warrants for fucking serious shit. I mean, straight to jail shit. Do not pass go, do not collect two hundred pounds shit. Membership of banned organisations, kidnapping, explosives, arson. Decades in jail shit, right?” A Vespa tore through the quiet, and the engine grabbed a breath as the driver changed gears. “And these guys are going outtomorrow, carrying hand guns—”

“You are fuckeeng scared, Rob.”

“Yeah, I’m fucking scared. These guys are carrying pistols because they don’t plan on being taken alive. That’s too much heat, man.”

“You sound like a fuckeeng scared hippy.”

“If someone shoots a cop, they’ll gun us down. Forget rubber bullets, they’re gonna—”

“Nobody shoot a fuckeeng cop. No wonder you so scared; you believe every rumour you hear. Listen, the last time I am at Hyde Park, an old man tell me that the fuckeeng world end on Friday.”

“So?”

“So you believe every rumour you never leave the house, eenit?”

“Look,” said the English guy, pointing at a stripy gecko on the wall of the Theology Building.

“I’m not a pacifist,” said Rob. “I was with the black bloc in Genoa, but I’m staying away from that shit tomorrow.”

Manette stood up, kicking the pins and needles out of her legs. “As long as you have my fuckeeng dinner ready when I get back. I go to find Hristos.” She threw her cigarette away and walked towards the Philosophy Building.

“And you?” asked the English guy. I shrugged and ran after Manette.

“Fuckeeng hippy wanker. As long as I know him he is crying about police brutality, but as soon as anyone start fighting back, he fuckeeng run away.” The Philosophy Building was guarded by a man in an unbuttoned sleeveless shirt, who sat on a broken wooden chair, chewing gum and tapping his palm with a short club. Inside, our feet crunched on broken glass. The paint fumes made you feel drunk, and the slogans were hard to read because so many lights were broken. “By any means necessary.” “The Future is Unwritten.” “Ultras AEK.” “No War Between Nations, No Peace Between Classes.” The shadows, and the people in the shadows, and the closed doors, carried the suggestion of an ambush, so I found myself looking left and right, as if crossing a road.

Climbing the stairs, I stopped on the landing, and through the window I watched the square below: the intense conversations, Alex’s comrades wielding sticks beneath the lights of the Theology Building, the rest of the campus black and quiet, and, beyond that, the city. You could hear the noise of a dog barking in the distance.

At the top of the stairs, at the end of a corridor where the air was thick with petrol, a man stood in boot-cut jeans, wearing his Ray-Bans folded over the V of his polo shirt. “What?” said Manette.

“Is nobody can come in here.”

“We are friends of Hristos.”

“Sorry, is nobody can come in here.”

“Well, fuckeeng tell Hristos Manette come here to see him.”

A female voice said, “Nikos, ti néa?”

“Eva, you know where is Hristos?”

“Ékso, méh Yiorgos.”

“Hristos go out, sorry. Maybe after he come here.” Fumes tumbled through the doorway, intoxicating, like the runaway train smell of diesel.

Thessaloniki, 20th June 2003. I choked through a cigarette, and then I stretched and joggled my arms, like a sprinter waiting for starter’s orders. When you sleep on concrete, your body is so many hard bits: elbows and wrists, hips and knees. Manette spat toothpaste into the dusty ground, and, all around us, people rolled their shoulders and pressed their backs. A man washed his shaved head under a bottle of water and then hooted and shook himself like a dog. Meanwhile, the sun climbed over the Law Building, shooting up the morning.

When they had finished their coffee, Alex and his comrades tried on gasmasks: police-issue modern respirators with full face visors, or World War II relics with round eye holes and long snouts. They fitted motorcycle helmets and hit themselves, shaking their heads like boxers. They strapped shin-pads to their forearms and distributed red and black flags tacked onto sticks shaped like baseball bats. Manette accepted a flag, swung at a rose bush, and then rested it against the wall. She tied a bandanna tight over the bridge of her nose, laughed, and punched my arm. “You ready for some sport, Petit Fantôme?” A girl with ski goggles round her neck tugged a brush through her hair. A Spanish boy, talking through a decorating mask (the sort of thing you’d wear to sand a floor), asked if I knew where he could get ball bearings for his slingshot. Two guys fought a sword fight with sticks. There were girls with T-shirts wrapped round their faces jihad-style. Guys who’d got too hot in their balaclavas had rolled them up so they sat on top of their heads. There was a Greek girl, in low cut jeans, bikini top and a bandanna, leaning in the shade, holding a petrol bomb.

Midmorning, a rucksack went on fire, and a toxic smelling smoke rose in front of the Philosophy Building. The rucksack’s owner beat the flames with a long stick, looking somewhere between guilty and amused, while all the time the sun climbed higher, and I waited, just wanting it over now.

There were five hundred people in our bloc, formed into a tight rectangle and enclosed by flagpoles. We left the University when the sun was directly overhead, burning up Odhós Egnatías, blistering the tarmac, swelling cracks in the concrete. There were no cars. No pedestrians. Running bare to the horizon, where heat waves swayed and mottled the air, the highway carried a road movie’s invitation to adventure, and it filled me with a reckless sense of freedom.

I didn’t feel trapped, though there was now no option but to be carried with the bloc; instead, I felt a sort of anticipation. I said to Manette, “I want to do this!” I wanted the proximity, the immediacy. I wanted to stand toe to toe with a cop and fight it out. He’d hit me with his truncheon and I’d swing back with my stick and this seemed real, it seemed—

Then the insurrectionists, thousands of them, spilled onto the road behind us. They smashed traffic lights and street signs. Men in black hoods pushed a supermarket trolley filled with molotov cocktails. They bumped it down the university steps, landing it wheels askew. Then they charged, struggling to steer straight. A helicopter swung over the flats, gargling a circle above us. Windows smashed. The insurrectionists shot fireworks at journalists on rooftops. They attacked the offices of the Communist Party, breaking through the door with an axe.

But we held our formation. We turned right and climbed the slope. From behind me, I heard the whoosh of petrol. Looking back, I saw flames jumping two stories high from the Communist offices. We marched between lines of parked cars, until we reached a crossroads where the police surrounded us. We stopped, and they stood still, so we faced each other, just metres apart. There were some with batons and shields, and others with knapsacks stuffed with gas grenades. Some wielded big guns, and others held pipes fed by cylinders mounted on their backs. And my sense of freedom slipped away, replaced not just by fear, but by a familiar powerlessness. I watched a Greek girl load her slingshot and fire a pellet that bounced high off body armour, and I waited, huddled inside myself, knowing it had to kick off. Yet somehow it didn’t. The bloc rotated and shuffled down a narrow street, an extreme left turn that led back to Odhós Egnatías.

And from there, looking towards the university, you could see petrol bombs cartwheeling, luminous orange against the black smog. You could hear the battle—the explosions, the clatter of axes tearing into metal shop fronts—but all you could see was this fireworks display of molotovs, gas bombs, and phosphorescent flares, arcing against the black sky. Then shouting and pushing spread from the back of our bloc, people ran, explosions fused

into one big noise, and in five seconds everyone had disappeared. I was gasping, trying to clear a space in my lungs by inhaling more gas. I no longer knew which way to run, so I stood there. I held my stick. I felt a tug on my shirt. Manette shouted, “Allez quoi! Fuckeeng run!”

When we stopped, bent over, skin burning as we pressed our chests, I saw that behind us, the road was clouded with gas and smoke. It reminded me of the way clouds look from aeroplanes. There were men with gasmasks running out of the cloud—some carrying captured police equipment—while others were running into it, throwing rocks and petrol bombs. There was a shop on fire and a girl vomiting watery puke. There was a man sitting on the road, naked except for shorts and a bandanna, bleeding from a wound above his eye.

“You okay, Petit Fantôme?”

“Aye.”

“You look even whiter.”

“I want a cigarette.”

“You can’t fuckeeng smoke with that in your lungs.”

“Can I have some water?”

She took off her rucksack and passed me the water, but before I could drink, people ran past me, and though I couldn’t see what they were running from, I followed until we stopped in a big square. The gas drifted from far away, and to my left, a tree was on fire. A boy with red eyes was groping and crying “Parakaló! Parapeace, kaló!” Manette led him by the arm to one of our medics. A guy in cut-off trousers hacked the tarmac with an axe, smashing it into pieces we could throw. Everywhere, people were coughing and spitting. Then someone shouted “Batsi! Batsi!” and I saw green uniforms at the far corner of the square. We edged forward, firing slingshots, hurling rocks and bottles, gas canisters, a foot of lead pipe, a broken wing mirror. “Petit Fantôme, look,” said Manette, running across the road. Men in motorcycle helmets were ripping axes into the aluminium shutter of Benny’s Burgers. I wanted to write something, to claim the destruction for the workers, but before I could find my paint, a burst of fire had filled the crack in the shutter. As Manette ran back to me, the sweat glistened on her chest. Then she veered and accelerated, her rucksack bouncing on her back, as the sky disappeared and the gas canisters exploded. I was just a second behind her, carried in the stampede. “Sigá sigá!” As the panic pushed one group to the right and the other straight-ahead, we realised what was happening and reached for each other with our eyes, helpless to prevent this separation.

An hour later, I hid in a bar, and the proprietor, a woman with varicose veins and a brown contoured face, must have noticed the white CS powder stains on my trousers, or my red eyes, because she smiled at me and changed the television to the news from which I had just escaped. The streets looked quiet now. Police patrolled in gasmasks. Fire crews hosed smouldering shop fronts. A bush remained ablaze at the roadside, and a litter bin burned in the middle of the highway. The air was hazy with smoke and spray and steam. A group of children edged into the frame, wanting to see the aftermath of what they’d watched on TV. They were dressed to imitate the anarchists, with their T-shirts pulled over their faces, wielding our discarded sticks with both hands. When a cop pretended to run at them, they dropped the sticks and scattered.

They cut back to the studio. The TV was muted and I was alone in the bar so the only noise was the fan on the ceiling. As the TV started doing replays, showing the highlights, I decided it would be safe to smoke. It was strange to sit there and see what had really happened. The gas wasn’t as opaque as I remembered, and I seemed to have overestimated how many of us there were at certain points. For example, in the footage of the destruction of Benny’s, filmed from a rooftop or maybe a helicopter, there were only a dozen people on the screen. Nobody running. No police. I couldn’t see Manette, or myself, and I began to wonder if we’d been there.

Then a map came on the screen, and there was some sort of analysis, with arrows showing the movements of demonstrators and police. It was like something you’d see on Match of the Day. “This is early on, Gary. Look at the position the anarchists are in; I mean, defensively, it’s cavalier.” Then more highlights, petrol bombs, an injured cop. Then the scene from the leftist demonstration: the street congested, the tightly organised blocs trying to press towards the railway station, away from the fighting. Behind them, thick smoke rises into the blue sky, and the helicopter circles overhead like a buzzard. Then an arrest: someone beaten to the ground and pinned on the pavement.

When they showed him without his mask, I saw it was the English guy from the university, Simon. I wanted to help him, to do something. And that, of course, is exactly what the spectacle precludes.