Posted on May 11th, 2009 in AK Book Excerpts

Our most recent book back from the printer is Barry Sanders’s The Green Zone: The Environmental Costs of Militarism. It’s a detailed examination of the environmental impact of US military practices—which identifies those practices, from fuel emissions to radioactive waste to defoliation campaigns, as the single-greatest contributor to the worldwide environmental crisis. We think it’s a powerful book, especially considering the fact that the Obama regime’s efforts to save capitalism through new, “ecological” modes of production—disingenuous and doomed as they are—won’t even begin to address the environmental and climactic havoc wreaked by the planet’s most destructive enemy: the US military.

Our most recent book back from the printer is Barry Sanders’s The Green Zone: The Environmental Costs of Militarism. It’s a detailed examination of the environmental impact of US military practices—which identifies those practices, from fuel emissions to radioactive waste to defoliation campaigns, as the single-greatest contributor to the worldwide environmental crisis. We think it’s a powerful book, especially considering the fact that the Obama regime’s efforts to save capitalism through new, “ecological” modes of production—disingenuous and doomed as they are—won’t even begin to address the environmental and climactic havoc wreaked by the planet’s most destructive enemy: the US military.

Below is a short excerpt from Barry’s Introduction…

* * *

Over the years, my family has bought three or four little books on how to lead the greenest life possible. We’ve all seen those well-intentioned pamphlets at the checkout counters of bookstores and grocery stores: Fifty Ways to Save the Planet; Going Totally Green; Making a Difference; and so on. While they may pale these days considering the enormity of the environmental crisis, we nonetheless still take the advice to heart, choosing low-energy light bulbs, installing low-flush toilets, turning down the thermostat, refusing to warm up the car’s engine for extended periods, and on and on. Every little bit helps, as the experts tell us, and, besides, we need to feel that we are doing something. But no list in any of those books addresses the largest single source of pollution in this country and in the world: the United States military—in particular, the military in its most ferocious and stepped-up mode—namely, the military at war.

In a nation like ours, where military might trumps diplomatic finesse, the supreme irony may be that the planet, and not human beings, will provide the most stringent corrective to political overreaching. The earth can no longer absorb the punishment of war, especially on a scale and with a ferocity that only the wealthiest, most powerful country in the world—no, in history—knows how to deliver. While the United States military directed its “Operation Iraqi Freedom” solely against the Iraqis, no one—not a single citizen in any part of the globe—has escaped its fallout. When we declare war on a foreign nation, we now also declare war on the Earth, on the soil and plants and animals, the water and wind and people, in the most far-reaching and deeply infecting ways. A bomb dropped on Iraq explodes around the world. We have no way of containing the fallout. Technology fails miserably here. War insinuates itself, like an aberrant gene and, left unchecked, has the capacity for destroying the Earth’s complex and sometimes fragile system.

So we can act like honorable and conscientious citizens, conserving all the energy we can. We can feel good about all those glossy magazine ads from Shell and Exxon Mobil telling us how their companies now treasure the environment, producing their fuels in the cleanest ways possible. We can fall for Detroit’s latest news, too, convincing us of a revolutionary breakthrough in fuel efficiency: 300 horsepower cars that get still 30 or 32 miles per gallon on the highway. But that’s just insanity wearing a green disguise. None of those advertised boasts and claims really matter. They still cling to fossil fuels and further our campaign to kill off everything on the planet with our addictive need. But, even if those claims did make a slight difference, even if we could slow down global warming, ultimately it would not matter. For, in the background, lurking and ever-present, a giant vampire silently sucks out of the Earth all the oil it possibly can, and no one stops it. And so here’s the awful truth: even if every person, every automobile, and every factory suddenly emitted zero emissions, the Earth would still be headed head first and at full speed toward total disaster for one major reason. The military—that voracious vampire—produces enough greenhouse gases, by itself, to place the entire globe, with all its inhabitants large and small, in the most immanent danger of extinction.

As we contemplate America in the opening years of the twenty-first century, then, let us reconsider George Washington’s farewell warning that “overgrown military establishments…under any form of government, are inauspicious to liberty, and are to be regarded as particularly hostile to republican liberty.” Today, our own military has grown beyond an institution hostile to liberty and has wrapped its arms of death around life itself. And, from all the available evidence, it will not let go. Unlike most animals, the military has no surrender mechanism. Unless we all summon the strength to confront the military—no easy task—it will continue to work its evil.

I write as a citizen, not a politician; as a layman, not a scientist; as an outsider from the academy, not an insider from the Pentagon. Most of the information that I present here is deliberately withheld from the general public, made intentionally obscure, folded inside arcane reports, or hidden on hard-to-find governmental websites by the Department of Defense (DoD), or the Pentagon, or the General Accounting Office. Researching the military is like trying to uncover the truth in the former Soviet Union. Governments always conduct a good deal of their business in clandestine ways. The Bush administration, however, enjoyed the well-earned reputation as particularly deceptive, tight-lipped, secretive, and downright hostile to the most routine questions and probes—and especially over things that appeared so obviously illegal, like spying on citizens through wiretapping telephone calls and intercepting international e-mail messages, all without the legally required warrants. We will see how eager the Obama administration will be to reveal its inner workings. Transparency was one of the goals of Obama’s campaign, and he repeated that mantra over and over again….

But before we rejoice too soon in the new administration, recall that, directly before the election, Obama sounded very much like the old administration when he announced that he would probably need to send two more battalions into the foothills of Afghanistan. Bin Laden is still the prize; victory is still the illusion. War is still the way. The impulse toward war transcends parties: Republicans defend their war in Iraq; Democrats defend Kosovo. Saddam Hussein is a tyrant and practiced genocide on the Kurds. Slobodan Milosovic is a tyrant and practiced genocide on the Albanians. The names change, the nations shift, but the war drums reverberate with their same incessant and insistent beat. And almost everyone listens—conservatives and liberals—and almost everyone responds.

Posted on May 8th, 2009 in Reviews of AK Books

At AK Press, we love it when people read our books. And what do we love even more than that? When people read and review our books! That makes super, super happy.

With that in mind, we hope you’ll enjoy James Generic’s review of Real Utopia: Participatory Society for the 21st Century

* * *

Real Utopia: Participatory Society for the 21st Century

Real Utopia: Participatory Society for the 21st Century

Edited by Chris Spannos

AK Press, 2008

Review by James Generic

Parecon is an economic school coming from the libertarian socialist and anarchist school of thought, in opposition to traditional liberal economics or centrally planned economies. It seems to argue three basic things.

The first is that in society, there is a capitalist class, a working class, and a coordinator class, updating Marxist work of dividing the entirety of society into bourgeois and proletarian classes, with all else being outside the historical class struggle. Parecon argues that this really leaves out a coordinator class in modern capitalism. A class consisting of people like professors, professionals, managers, supervisors, police, small business owners and other people who do not own large means of production, but do in fact have powers over the working class as the experts of society. This would explain such phenomena like after the Russian Revolution where the Bolshevik Party became the new rulers, ruling in the name of the workers.

The second part of parecon theory explores future economies, and argues that society should be run by a mixture of workers councils running workplaces and consumer councils determining how to distribute goods and materials. Neighborhood organizations would also run neighborhoods, with any delegation being recallable. In addition, boards would plan out further economics.

Some of the other features are that where things effect people more, like if you live in a certain place, your voice means more. Another main feature is that “rote” work (or “shitwork”) and “empowering” work (enjoyable work) is regularly rotated. Participatory economics originated between work of Robin Hahnel and Michael Albert, much of which came from direct experience working in collectives. They try to emphasize deconstructing gender roles, ecology, democratic processes, fair distribution, balancing talent and time, education, and empowering work.

Real Utopia: Participatory Economics for the 21st Century, edited by Chris Spannos, is a collection of essays by not only Hanel and Albert, but a multitude of others who have developed parecon theory, used it in real collective work, and have written extensively in defense of participatory economics. It is divided into sections like theory; exploring how parecon could be used in a future post-capitalist world; how parecon can be used in places outside the US like Africa, the Balkans, or Argentina, applying parecon theory to historical examples like the Russian Revolution or the Spanish Revolution, or Social Democracy in the 20th century; parecon in practice from examples like South End Press, Mondragaon Bookstore and Cafe in Winnipeg, the Newstandard magazine, the Vancouver Parecon Collective, and the Austin Project for Participatory Society; and then how to incorporate parecon into larger social movements and fights for social justice and a new world.

(more…)

Posted on May 6th, 2009 in AK Allies, Happenings

The Institute for Anarchist Studies has launched their brand new, and very spiffy, website. It’s still somewhat under construction, but you should visit it soon and often. They’ve launched it with four essays about the late Murray Bookchin (who AK had the great privilege of working with over the last decade, both publishing and distributing his books). Here’s what IAS director Mark Lance has to say about the essays you’ll find on their site:

* * *

The following four articles are written by people who were in one way or another connected to Murray’s life and work. Brian Tokar surveys Murray’s vast contribution to radical environmental thought. He reminds us of how far ahead of the rest of the world Murray’s ideas were, and also of how much they still have to offer a movement that frequently loses its radical edge in favor of accommodation with the very social forces that ground our antagonistic relationship with the Earth in the first place.

Next, John Clarke takes up Murray’s well-known attack on contemporary anarchist practice, specifically his charge that anarchism as it exists in contemporary society has moved towards a shallow sort of individualism. Clarke’s discussion is highly critical, but offers just the sort of intellectual and argumentative ferment that Murray reveled in.

Chaia Heller offers a personal reflection on her many years as a close colleague of Murray’s. She reflects on him both as a thinker and as a friend, offering us images of how we might move forward in the work to which he devoted his life, drawing political lessons as much from the nature of the friendship as from the ideas in his books.

Finally, Chuck Morse, a student and comrade of Murray, offers a detailed and at times highly critical look at his organizing strategy. Though informed by Chuck’s deep understanding of Murray’s theoretical vision, the focus is on the ways Murray sought to institutionalize that vision, with the ultimate conclusion that it was deeply flawed.

In my view, Murray was the most important anarchist theorist of the 20th century. I’m sorry I never met the man in person, but am honored and pleased to have found a home in a community to which he was so central. I am pleased as well to have had a small role in bringing you these essays that continue engagement with his life and work into a new century.

Posted on May 4th, 2009 in AK Distribution

As you hopefully know, aside from publishing around 20 titles a year, AK Press also distributes over 3,000 other radical books, CDs, DVDs, t-shirts, and other good stuff to individuals, groups, and stores all over the world. Since distribution is a big part of what we do at AK, we’re always trying to bring in new items to keep our catalog fresh and to make sure we have what folks are looking for. So, since there’s always good stuff coming in, every month on our blog we’ll let you know the highlights of what’s new. If you’d like to get more frequent updates by e-mail (we aim for twice a month), please join our mailing list: http://www.akpress.org/contact/mailinglist

This month you might notice an environmental theme to several of our new distro titles—which is probably because publishers tend to time the releases of their new “green” books to coincide with Earth Day, as AK Press did with The Green Zone (http://www.akpress.org/2009/items/greenzoneakpress). We’re all very clever!

As a side note, we’re always looking to make contact with new publishers, distros, and stores, too—so please drop us a line if you want to suggest new items we should be carrying, or if you’d like to join our network of tablers or stock your infoshop with new titles.

*TOP 10 NEW ARRIVALS IN APRIL*

EXPOSED: The Toxic Chemistry of Everyday Products — By Mark Schapiro. This one was a hit in hardcover when we shared a booth with Chelsea Green Publishing at the Green Festival last year, but now that it’s out in paperback, even people who don’t attend Green Festivals can afford it! A great (and shocking) look at the toxic chemicals that lurk where you least expect them. http://www.akpress.org/2009/items/exposed

EXPOSED: The Toxic Chemistry of Everyday Products — By Mark Schapiro. This one was a hit in hardcover when we shared a booth with Chelsea Green Publishing at the Green Festival last year, but now that it’s out in paperback, even people who don’t attend Green Festivals can afford it! A great (and shocking) look at the toxic chemicals that lurk where you least expect them. http://www.akpress.org/2009/items/exposed

VEGAN SOUL KITCHEN: Fresh, Healthy, and Creative African-American Cuisine — By Bryant Terry. There was a great vegan soul food restaurant in Oakland for a minute. Then it closed and we were all thrown into despair. But now we have this: a new cookbook full of vegan soul food we can make right in our own kitchens! It’s by a local chef, too, so maybe there’s hope for an Oakland vegan soul food revival… http://www.akpress.org/2009/items/vegansoulkitchen

VEGAN SOUL KITCHEN: Fresh, Healthy, and Creative African-American Cuisine — By Bryant Terry. There was a great vegan soul food restaurant in Oakland for a minute. Then it closed and we were all thrown into despair. But now we have this: a new cookbook full of vegan soul food we can make right in our own kitchens! It’s by a local chef, too, so maybe there’s hope for an Oakland vegan soul food revival… http://www.akpress.org/2009/items/vegansoulkitchen

POETS FOR PALESTINE — Edited by Remi Kanazi. One of the more impressive local shows I’ve seen in the past few years was a hip-hop/spoken word show featuring several touring groups of mostly Palestinian artists—so imagine my delight when we got this in and I looked at the table of contents. It’s some of the same acts I remembered from that show—the N.O.M.A.D.S, Nizar Wattad (Ragtop)—but also some big-name poets like Amiri Baraka, Naomi Shihab Nye, and Mahmoud Darwish. Interspersed with some stunning black-and-white art. http://www.akpress.org/2009/items/poetsforpalestine

POETS FOR PALESTINE — Edited by Remi Kanazi. One of the more impressive local shows I’ve seen in the past few years was a hip-hop/spoken word show featuring several touring groups of mostly Palestinian artists—so imagine my delight when we got this in and I looked at the table of contents. It’s some of the same acts I remembered from that show—the N.O.M.A.D.S, Nizar Wattad (Ragtop)—but also some big-name poets like Amiri Baraka, Naomi Shihab Nye, and Mahmoud Darwish. Interspersed with some stunning black-and-white art. http://www.akpress.org/2009/items/poetsforpalestine

IN AND OUT OF THE WORKING CLASS — By Michael D. Yates. Yates is a pretty prolific writer (see our other recent arrival by him, the new edition of WHY UNIONS MATTER). But this book is unique among them—instead of another objective analysis, what he gives us here is both personal and political. He draws on his own expertise as a political economist to explain different facets of his own life experience, and the end result is this collection of semi-autobiographical essays on the complexities of class and identity. http://www.akpress.org/2008/items/inandoutofworkingclass

IN AND OUT OF THE WORKING CLASS — By Michael D. Yates. Yates is a pretty prolific writer (see our other recent arrival by him, the new edition of WHY UNIONS MATTER). But this book is unique among them—instead of another objective analysis, what he gives us here is both personal and political. He draws on his own expertise as a political economist to explain different facets of his own life experience, and the end result is this collection of semi-autobiographical essays on the complexities of class and identity. http://www.akpress.org/2008/items/inandoutofworkingclass

IN SEARCH OF THE LOST TASTE — By Joshua Ploeg. Some (OK, most) of the recipes here are weird-sounding enough that you just know they must be delicious. The table of contents reads like the menu of a fancy restaurant, with all its yummy-sounding sauces, spreads, reductions, and relishes…and yet you won’t need the budget of a fancy restaurant to try out these recipes. Joshua Ploeg is the former singer of Behead the Prophet, Mukilteo Fairies and Lords of Lightspeed (I’m pretty uncool myself, so I’m just pretending I know who these bands are). He is now a vegan touring chef to the stars! http://www.akpress.org/2008/items/insearchoflosttaste

IN SEARCH OF THE LOST TASTE — By Joshua Ploeg. Some (OK, most) of the recipes here are weird-sounding enough that you just know they must be delicious. The table of contents reads like the menu of a fancy restaurant, with all its yummy-sounding sauces, spreads, reductions, and relishes…and yet you won’t need the budget of a fancy restaurant to try out these recipes. Joshua Ploeg is the former singer of Behead the Prophet, Mukilteo Fairies and Lords of Lightspeed (I’m pretty uncool myself, so I’m just pretending I know who these bands are). He is now a vegan touring chef to the stars! http://www.akpress.org/2008/items/insearchoflosttaste

THE ANIMAL ACTIVIST’S HANDBOOK: Maximizing Our Positive Impact in Today’s World — By Matt Ball & Bruce Friedrich. The premise here is pretty simple…rocket scientist goes vegan and starts Vegan Outreach (an animal rights organization); student drops out of college, works at a Catholic Worker soup kitchen, goes vegan and later becomes the vice president of PETA; the two come together to reflect on their experiences, successes, and missteps. Here’s a simple guide for all you aspiring animal rights activists out there, so you don’t have to reinvent the wheel! http://www.akpress.org/2009/items/animalactivistshandbook

THE ANIMAL ACTIVIST’S HANDBOOK: Maximizing Our Positive Impact in Today’s World — By Matt Ball & Bruce Friedrich. The premise here is pretty simple…rocket scientist goes vegan and starts Vegan Outreach (an animal rights organization); student drops out of college, works at a Catholic Worker soup kitchen, goes vegan and later becomes the vice president of PETA; the two come together to reflect on their experiences, successes, and missteps. Here’s a simple guide for all you aspiring animal rights activists out there, so you don’t have to reinvent the wheel! http://www.akpress.org/2009/items/animalactivistshandbook

HEAT: How to Stop the Planet From Burning — By George Monbiot. There’s been a big push behind this book from our friends at South End Press, and that makes sense. It’s a message that needs to get out sooner rather than later. The premise of the book is that we all know climate change is happening, and it’s still scientifically possible to reverse it by making specific changes, but those changes must be immediate and decisive—there’s no time to waste. http://www.akpress.org/2009/items/heatpb Also available as a sale-priced hardcover: http://www.akpress.org/2007/items/heathowtostoptheplanetfromburning

HEAT: How to Stop the Planet From Burning — By George Monbiot. There’s been a big push behind this book from our friends at South End Press, and that makes sense. It’s a message that needs to get out sooner rather than later. The premise of the book is that we all know climate change is happening, and it’s still scientifically possible to reverse it by making specific changes, but those changes must be immediate and decisive—there’s no time to waste. http://www.akpress.org/2009/items/heatpb Also available as a sale-priced hardcover: http://www.akpress.org/2007/items/heathowtostoptheplanetfromburning

MIX TAPES & COTTON 7″ LP — By Drowning Dog. This is the latest release from our comrades, anarchist hip-hop artists Drowning Dog and Malatesta of Entartete Kunst. An honest, personal look at growing up working-class and the experiences of racism, sexism, and capitalist oppression. Short, to the point, and put out by lovely folks we are glad to support! http://www.akpress.org/2009/items/mixtapesandcotton

MIX TAPES & COTTON 7″ LP — By Drowning Dog. This is the latest release from our comrades, anarchist hip-hop artists Drowning Dog and Malatesta of Entartete Kunst. An honest, personal look at growing up working-class and the experiences of racism, sexism, and capitalist oppression. Short, to the point, and put out by lovely folks we are glad to support! http://www.akpress.org/2009/items/mixtapesandcotton

ZAPATA OF MEXICO — By Peter Newell. All right, so this isn’t a new release at all—not even new to us. This edition was originally published thirty years ago by Black Thorn Books, and we got ahold of some copies a few years back, but we ran out pretty quickly and thought they were gone forever. Now we’ve located more, and they’re available again at a great price, while they last! http://www.akpress.org/2006/items/zapataofmexicoblackthornbooks

ZAPATA OF MEXICO — By Peter Newell. All right, so this isn’t a new release at all—not even new to us. This edition was originally published thirty years ago by Black Thorn Books, and we got ahold of some copies a few years back, but we ran out pretty quickly and thought they were gone forever. Now we’ve located more, and they’re available again at a great price, while they last! http://www.akpress.org/2006/items/zapataofmexicoblackthornbooks

ARMITAGE AVENUE TRANSCENDENTALISTS — A great find for anyone who’s ever lived in Chicago, been fascinated by Chicago, or even wanted to go to Chicago, this is an edited collection of pieces on the city and its unique history and cast of characters. Includes pieces from contributors as wide-ranging as Franklin and Penelope Rosemont, Studs Terkel, Eduardo Galeano, and Daniel Pinkwater (who, incidentally, wrote a book about werewolves and beat poets that I really enjoyed as a kid). http://www.akpress.org/2009/items/armitageavenuetranscendentalists

ARMITAGE AVENUE TRANSCENDENTALISTS — A great find for anyone who’s ever lived in Chicago, been fascinated by Chicago, or even wanted to go to Chicago, this is an edited collection of pieces on the city and its unique history and cast of characters. Includes pieces from contributors as wide-ranging as Franklin and Penelope Rosemont, Studs Terkel, Eduardo Galeano, and Daniel Pinkwater (who, incidentally, wrote a book about werewolves and beat poets that I really enjoyed as a kid). http://www.akpress.org/2009/items/armitageavenuetranscendentalists

* * *

If you made it this far, then you also deserve to know where to find the cheap books! Since we know it’s tough times all around, and we have kind of a lot of good books here, each week we’re discounting new titles and selling them for $5 until we run out. Have a look, why don’t you! http://www.akpress.org/2005/topics/sale

Till next time!

Posted on April 29th, 2009 in Happenings, May Day

Tomorrow is Mayday. For the past couple of weeks, we’ve been posting things related to the international workers’ day. This time around, we thought we’d share an excerpt from Peter Linebaugh’s “The Incomplete, True, Authentic, and Wonderful History of May Day,” which originally appeared in 1986 (hence the reference to the Soviet Union). Peter outlines the long, indeed ancient, history of Mayday, from it’s “green” origins as a celebration of spring to it’s “red” associations with organized, and persecuted, labor.

Tomorrow is Mayday. For the past couple of weeks, we’ve been posting things related to the international workers’ day. This time around, we thought we’d share an excerpt from Peter Linebaugh’s “The Incomplete, True, Authentic, and Wonderful History of May Day,” which originally appeared in 1986 (hence the reference to the Soviet Union). Peter outlines the long, indeed ancient, history of Mayday, from it’s “green” origins as a celebration of spring to it’s “red” associations with organized, and persecuted, labor.

Below we’ve excerpted Peter’s brief introduction and a section about Haymarket.

You can read the entire essay on the Midnight Notes website. Or, if you’re more inclined toward hard copy, AK carries it as a nice, glossy pamphlet.

—–

A Beginning

The Soviet government parades missiles and marches soldiers on May Day. The American government has called May First “Loyalty Day” and associates it with militarism. The real meaning of this day has been obscured by the designing propaganda of both governments. The truth of May Day is totally different. To the history of May Day there is a Green side and there is a Red side.

Under the rainbow, our methodology must be colorful. Green is a relationship to the earth and what grows therefrom. Red is a relationship to other people and the blood spilt there among. Green designates life with only necessary labor; Red designates death with surplus labor. Green is natural appropriation; Red is social expropriation. Green is husbandry and nurturance; Red is proletarianization and prostitution. Green is useful activity; Red is useless toil. Green is creation of desire; Red is class struggle. May Day is both.

The Red: Haymarket Centennial

The history of the modern May Day originates in the center of the North American plains, at Haymarket, in Chicago – “the city on the make” – in May 1886. The Red side of that story is more well-known than the Green, because it was bloody. But there was also a Green side to the tale, though the green was not so much that of pretty grass garlands, as it was of greenbacks, for in Chicago, it was said, the dollar is king.

Of course the prairies are green in May. Virgin soil, dark, brown, crumbling, shot with fine black sand, it was the produce of thousands of years of humus and organic decomposition. For many centuries this earth was husbanded by the native Americans of the plains. As Black Elk said theirs is “the story of all life that is holy and is good to tell, and of us two-leggeds sharing in it with the four-leggeds and the wings of the air and all green things; for these are children of one mother and their father is one Spirit.” From such a green perspective, the white men appeared as pharaohs, and indeed, as Abe Lincoln put it, these prairies were the “Egypt of the West”.

The land was mechanized. Relative surplus value could only be obtained by reducing the price of food. The proteins and vitamins of this fertile earth spread through the whole world. Chicago was the jugular vein. Cyrus McCormick wielded the surgeon’s knife. His mechanical reapers harvested the grasses and grains. McCormick produced 1,500 reapers in 1849; by 1884 he was producing 80,000. Not that McCormick actually made reapers, members of the Molders Union Local 23 did that, and on May Day 1867 they went on strike, starting the Eight Hour Movement.

A staggering transformation was wrought. It was: “Farewell” to the hammer and sickle. “Goodbye” to the cradle scythe. “So long” to Emerson’s man with the hoe. These now became the artifacts of nostalgia and romance. It became “Hello” to the hobo. “Move on” to the harvest stiffs. “Line up” the proletarians. Such were the new commands of civilization.

Thousands of immigrants, many from Germany, poured into Chicago after the Civil War. Class war was advanced, technically and logistically. In 1855 the Chicago police used Gatling guns against the workers who protested the closing of the beer gardens. In the Bread Riot of 1872 the police clubbed hungry people in a tunnel under the river. In the 1877 railway strike, Federal troops fought workers at “The Battle of the Viaduct.” These troops were recently seasoned from fighting the Sioux who had killed Custer. Henceforth, the defeated Sioux could only “Go to a mountain top and cry for a vision.” The Pinkerton Detective Agency put visions into practice by teaching the city police how to spy and to form fighting columns for deployment in city streets. A hundred years ago during the street car strike, the police issued a shoot-to-kill order.

McCormick cut wages 15%. His profit rate was 71%. In May 1886 four molders whom McCormick locked-out were shot dead by the police. Thus, did this ‘grim reaper’ maintain his profits.

Nationally, May First 1886 was important because a couple of years earlier the Federation of Organized Trade and Labor Unions of the United States and Canada, “RESOLVED…that eight hours shall constitute a legal day’s labor, from and after May 1, 1886.

On 4 May 1886 several thousand people gathered near Haymarket Square to hear what August Spies, a newspaperman, had to say about the shootings at the McCormick works. Albert Parsons, a typographer and labor leader spoke net. Later, at his trial, he said, “What is Socialism or Anarchism? Briefly stated it is the right of the toilers to the free and equal use of the tools of production and the right of the producers to their product.” He was followed by “Good-Natured Sam” Fielden who as a child had worked in the textile factories of Lancashire, England. He was a Methodist preacher and labor organizer. He got done speaking at 10:30 PM. At that time 176 policemen charged the crowd that had dwindled to about 200. An unknown hand threw a stick of dynamite, the first time that Alfred Nobel’s invention was used in class battle.

All hell broke lose, many were killed, and the rest is history.

“Make the raids first and look up the law afterwards,” was the Sheriff’s dictum. It was followed religiously across the country. Newspaper screamed for blood, homes were ransacked, and suspects were subjected to the “third degree.” Eight men were railroaded in Chicago at a farcical trial. Four men hanged on “Black Friday,” 11 November 1887.

“There will come a time when our silence will be more powerful than the voices you strangle today,” said Spies before he choked.

Posted on April 27th, 2009 in Happenings

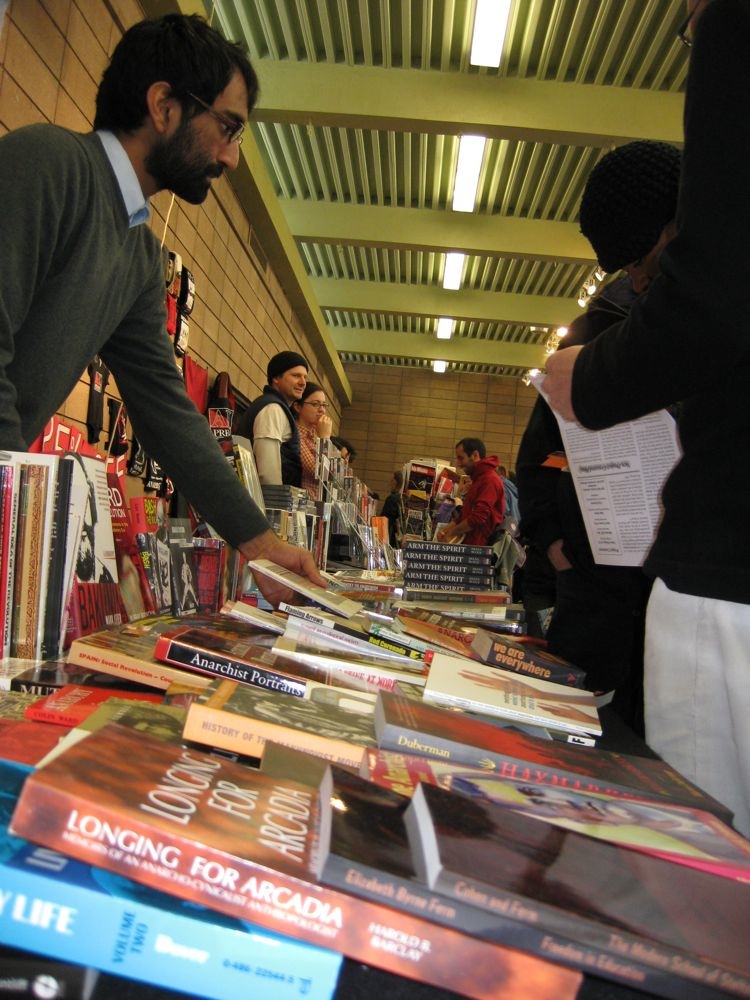

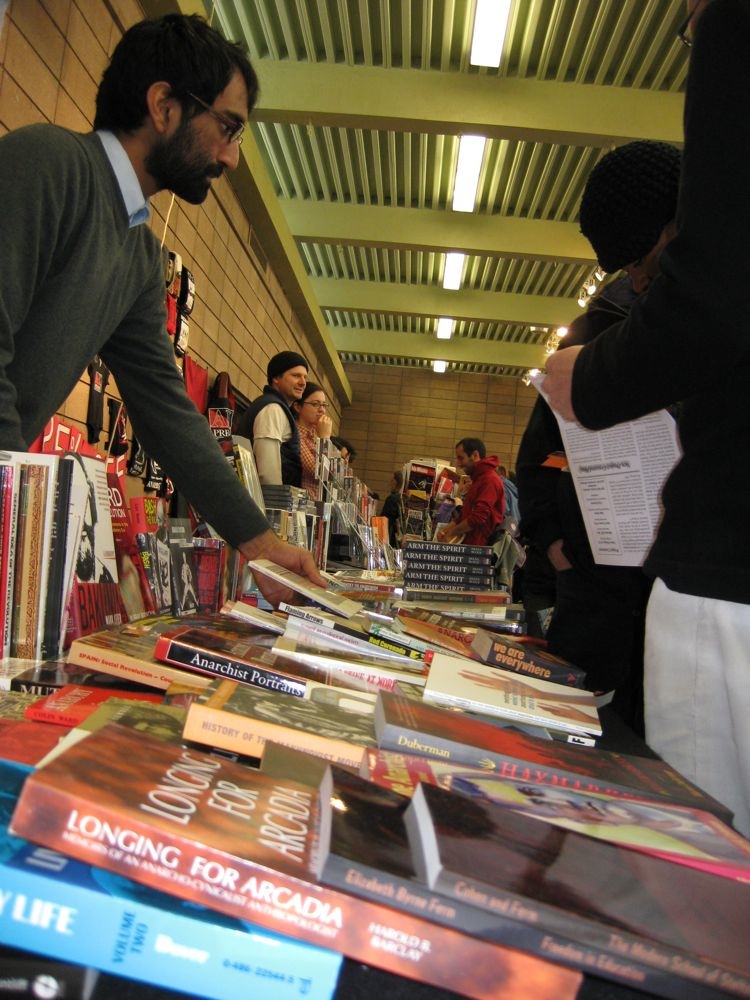

Over the last decade or so, book fairs have become an increasingly important way for anarchists to distribute literature, socialize, and talk about politics and strategy. They are now happening all over the world and with increasing frequency!

Over the last decade or so, book fairs have become an increasingly important way for anarchists to distribute literature, socialize, and talk about politics and strategy. They are now happening all over the world and with increasing frequency!

Here is a list of four scheduled to take place this year.

MADRID: May 21–24, 2009.

The CNT (Madrid) is organizing is a book fair that will take place in Madrid on May 21–24. For more information, go to this website.

GREECE: May 27–31, 2009

THE 4th BALKAN ANARCHIST BOOKFAIR will take place in Thessaloniki on May 27–28 and in Athens on May 29–31. Libertarian and anarchist publishers and comrades from all over the Balkans and beyond have been invited. The general theme of the presentations during the bookfair will be: “From the Balkans of exploitation and nationalism, to the Balkans of solidarity and struggle.” For more information, please go here.

SEATTLE: October 17 and 18, 2009

The Seattle Anarchist Book Fair will be take place on October 17-18 at the Underground Events Center. For more information, please go here.

CARACAS: November, 2009

Sponsored by the El Libertario publishing collective, the DOCUMENT (A) Libertarian Print and Audiovisual Documentary Fair will take place in the second half of November, 2009. More details will be available soon. For information, please write (preferably in Spanish) to feriaa.caracas2009@gmail.com.

Posted on April 24th, 2009 in May Day

All of us at AK Press want to encourage you to take a moment this May Day to recall the sacrifices and victories of earlier generations of militants who fought for a world without exploitation or domination of any sort. Let us never forget their legacy!

With this in mind, we repost a very thoughtful summary of the the origins of May Day from Chicago Indymedia. Of course, AK Press has many books and pamphlets on this topic. For a sampling, click here.

* * *

To Albert Parsons, August Spies, George Engel, Adolph Fischer, Louis Lingg, Michael Schwab, Samuel Fielden and Oscar Neebe. Your courage and sacrifice for the emancipation of labor–without borders–will never be forgotten.

May 1: International Worker’s Day – Día Internacional de los Trabajadores

“The time will come when our silence will be more powerful than the voices you are throttling today.” – August Spies from the gallows.

May 1st, International Workers’ Day, commemorates the historic struggle of working people throughout the world, and is recognized in every country except the United States and Canada. This despite the fact that the holiday began in the 1880s in the United States, with the fight for an eight-hour work day.

May 1st, International Workers’ Day, commemorates the historic struggle of working people throughout the world, and is recognized in every country except the United States and Canada. This despite the fact that the holiday began in the 1880s in the United States, with the fight for an eight-hour work day.

In 1884, the Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions passed a resolution stating that eight hours would constitute a legal day’s work from and after May 1, 1886. The resolution called for a general strike to achieve the goal, since legislative methods had already failed. With workers being forced to work ten, twelve, and fourteen hours a day, rank-and-file support for the eight-hour movement grew rapidly, despite the indifference and hostility of many union leaders. By April 1886, 250,000 workers were involved in the May Day movement.

The heart of the movement was in Chicago, organized primarily by the anarchist International Working People’s Association. Businesses and the state were terrified by the increasingly revolutionary character of the movement and prepared accordingly. The police and militia were increased in size and received new and powerful weapons financed by local business leaders. Chicago’s Commercial Club purchased a $2000 machine gun for the Illinois National Guard to be used against strikers. Nevertheless, by May 1st, the movement had already won gains for many Chicago clothing cutters, shoemakers, and packing-house workers. But on May 3, 1886, police fired into a crowd of strikers at the McCormick Reaper Works Factory, killing four and wounding many. Anarchists called for a mass meeting the next day in Haymarket Square to protest the brutality.

The meeting proceeded without incident, and by the time the last speaker was on the platform, the rainy gathering was already breaking up, with only a few hundred people remaining. It was then that 180 cops marched into the square and ordered the meeting to disperse. As the speakers climbed down from the platform, a bomb was thrown at the police, killing one and injuring seventy. Police responded by firing into the crowd, killing one worker and injuring many others.

Although it was never determined who threw the bomb, the incident was used as an excuse to attack the entire Left and labor movement. Police ransacked the homes and offices of suspected anarchists and socialists, and hundreds were arrested without charge. Anarchists in particular were harassed, and eight of Chicago’s most active—Albert Parsons, August Spies, George Engel, Adolph Fischer, Louis Lingg, Michael Schwab, Samuel Fielden and Oscar Neebe—were charged with conspiracy to murder in connection with the Haymarket bombing. A kangaroo court found all eight guilty, despite a lack of evidence connecting any of them to the bomb-thrower (only one was even present at the meeting, and he was on the speakers’ platform), On August 19th seven of the defendants were sentenced to death, and Neebe to 15 years in prison. After a massive international campaign for their release, the state “compromised” and commuted the sentences of Schwab and Fielden to life imprisonment. Lingg cheated the hangman by committing suicide in his cell the day before the executions. On November 11th 1887 Albert Parsons, George Engel, August Spies and Adolf Fischer were hanged. (more…)

Posted on April 24th, 2009 in Happenings, May Day

In honor of May Day, producers of the award winning documentary Made in L.A. are making a nation-wide effort to share the film and put a human face on the issues of immigration, immigrant workers’ rights, and humane immigration reform. Please consider hosting a screening or helping promote the campaign in other ways. For information about the film and how to participate in the effort, please go here.

Posted on April 22nd, 2009 in Reviews of AK Books

We love it when people review AK books! The following review by Ron Jacobs first appeared in Counterpunch. We repost it here with permission.

* * *

A Review of Diana Block’s Arm the Spirit

Artifacts for Survival

By RON JACOBS

In a nation like the United States, where history is not only forgotten, but intentionally suppressed, it is no surprise that most US residents do not understand the Puerto Rico is a colony of Washington. Consequently, it is also no surprise that very few people in the US know about the movement against Washington’s colonization and for Puerto Rican independence. Of those who are aware of the situation, many are convinced that the movement for Puerto Rican independence is composed of nothing but a few dozen “terrorists” who deserve to spend the rest of their lives in prison. Of those who actually support the independentista movement, many would be surprised that its members and supporters include folks different nationalities and backgrounds.

In a nation like the United States, where history is not only forgotten, but intentionally suppressed, it is no surprise that most US residents do not understand the Puerto Rico is a colony of Washington. Consequently, it is also no surprise that very few people in the US know about the movement against Washington’s colonization and for Puerto Rican independence. Of those who are aware of the situation, many are convinced that the movement for Puerto Rican independence is composed of nothing but a few dozen “terrorists” who deserve to spend the rest of their lives in prison. Of those who actually support the independentista movement, many would be surprised that its members and supporters include folks different nationalities and backgrounds.

Diana Block’s recently published book Arm the Spirit: A Woman’s Journey Underground and Back is the personal tale of one such supporter. A white North American woman involved in the feminist, lesbian and gay rights and new left movements in the United States of the 1970s primarily as a member of the Prairie Fire Organizing Committee (PFOC) , Ms. Block joined forces with other white North Americans to support the endeavors of the Fuerzas Armadas de Liberación Nacional (FALN ) in its endeavor to free Puerto Rico. Her support resulted in several years underground as the result of her partner’s entrapment in an FBI sting operation. The tale she tells in these pages is the story of those years and the decisions and circumstances that brought her to them. It is also the story of her family’s lives underground. For those who were involved in or at least paid attention to the left in the 1970s and 1980s there will be descriptions of moments that jog the memory. For those that didn’t, this will open their eyes to the reality that existed within Ronald Reagan’s morning in America.

This is a very political book. It is also a very personal book. It is about lives determined as much by one’s political beliefs as they are by personal emotions and about the juncture between the two. It is about very political people in an apolitical time. Many of those who had been involved in the antiwar and antiracist moments of the 1960s and 1970s were moving their lives into more conventional arenas that involved making money and buying things. Others, meanwhile, had drifted deeper into the life of the street and poverty, leaving their political personas behind in the daily struggle to survive. Meanwhile, the men and women involved in leftist groups like Prairie Fire Organizing Committee were existing on the fringes of US society trying to figure out how to maintain a political relevance. It may have been that existence on the outside that colored the decisions they made: going underground when they maybe should have involved themselves in a more public type of organizing; adopting immovable positions that alienated them from other groups with similar agendas, to name a couple such decisions.

Block’s memories of that period are consistently evocative and occasionally emotionally wrenching, compelling the reader to stay glued to the text. Her reflections on the thoughts about how the decisions made by her and her partner Claude Marks affected the lives of their children and families reveal caring and thoughtful parents whose politics are motivated by a love as deep as the love they have for those closest to them. They also provide an insight into the difficulties involved in living a life of resistance inside the belly of the imperial beast that is the United States. To put it succinctly, it is safe to say that Arm the Spirit is about the multitude of forms love takes: familial, romantic, comradely and revolutionary. It is also about the difficulties we face trying to meet the ideals these loves represent, especially when they come into conflict with one another.

Besides the aforementioned political and emotional realities revealed in this book, there are the descriptions of daily life on the run. Periods of normalcy when you and your family are as normal as the neighbors next door interrupted by days and weeks of uncertainty tinged with fear after your picture makes the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted. Joy and tears as you wrestle with how much information you should share with your maturing child.

Genuine friendships made under assumed names that must be broken when the presence of the law gets too near. The frustrations felt because your political self can not speak out when the Empire attacks for fear you will be recognized and taken away in chains. The decision to finally give up your underground status and face the courts. The period of adjustment to once again using your family name and living as the person you couldn’t be while underground.

Politically, Block’s experiences as a revolutionary and a woman lead her to a conclusion perhaps best expressed by the writer and revolutionary Margaret Randall: that the inability of almost all twentieth-century revolutionary movements to develop a feminist agenda contributed to their failure to evolve new and equitable forms of power sharing that might have helped keep them alive. The period of adjustment mentioned in the previous paragraph provokes some other interesting observations by Block. Foremost among them are her observations regarding the changes in the progressive movement in the 1970s and the movement today, especially her remarks that much of the work formerly done by organizations with no financial portfolio now being done by what she calls the nonprofit industrial complex.

The shortcomings of this movement are even more apparent today as funding for these nonprofits dries up in the wake of the economic shocks throughout the capitalist world. This factor doesn’t even touch the political timidity of many of today’s organizations—a timidity certainly influenced by their need to gather money from beneficiaries of the very system whose excesses and wrongs they hope to remedy.

One other insightful observation is that, despite the multitude of single issue movements and organizations, many of the groups and individuals involved have no underlying philosophy to bind these issues together and present a systemic analysis that would propel the struggle for economic and social justice forward. Although Block does not examine this much further, it is clear that she sees the need to develop and provide that analysis as part of the role of her and others involved in the struggles of the latter half of the twentieth century. After all, the fundamentals of that analysis are the same as those the left has always referred to. The economic crisis of capitalism and the wars of Washington make that clear.

Ron Jacobs is author of The Way the Wind Blew: A History of the Weather Underground, which is just republished by Verso. Jacobs’ essay on Big Bill Broonzy is featured in CounterPunch’s collection on music, art and sex, Serpents in the Garden. His first novel, Short Order Frame Up, is published by Mainstay Press. He can be reached at: rjacobs3625@charter.net

* * *

See also, Arm the Spirit! An interview with Diana Block.

Posted on April 20th, 2009 in Happenings

Our most recent book back from the printer is Barry Sanders’s The Green Zone: The Environmental Costs of Militarism. It’s a detailed examination of the environmental impact of US military practices—which identifies those practices, from fuel emissions to radioactive waste to defoliation campaigns, as the single-greatest contributor to the worldwide environmental crisis. We think it’s a powerful book, especially considering the fact that the Obama regime’s efforts to save capitalism through new, “ecological” modes of production—disingenuous and doomed as they are—won’t even begin to address the environmental and climactic havoc wreaked by the planet’s most destructive enemy: the US military.

Our most recent book back from the printer is Barry Sanders’s The Green Zone: The Environmental Costs of Militarism. It’s a detailed examination of the environmental impact of US military practices—which identifies those practices, from fuel emissions to radioactive waste to defoliation campaigns, as the single-greatest contributor to the worldwide environmental crisis. We think it’s a powerful book, especially considering the fact that the Obama regime’s efforts to save capitalism through new, “ecological” modes of production—disingenuous and doomed as they are—won’t even begin to address the environmental and climactic havoc wreaked by the planet’s most destructive enemy: the US military.

Tomorrow is Mayday. For the past couple of weeks, we’ve been posting things related to the international workers’ day. This time around, we thought we’d share an excerpt from Peter Linebaugh’s “The Incomplete, True, Authentic, and Wonderful History of May Day,” which originally appeared in 1986 (hence the reference to the Soviet Union). Peter outlines the long, indeed ancient, history of Mayday, from it’s “green” origins as a celebration of spring to it’s “red” associations with organized, and persecuted, labor.

Tomorrow is Mayday. For the past couple of weeks, we’ve been posting things related to the international workers’ day. This time around, we thought we’d share an excerpt from Peter Linebaugh’s “The Incomplete, True, Authentic, and Wonderful History of May Day,” which originally appeared in 1986 (hence the reference to the Soviet Union). Peter outlines the long, indeed ancient, history of Mayday, from it’s “green” origins as a celebration of spring to it’s “red” associations with organized, and persecuted, labor. Over the last decade or so, book fairs have become an increasingly important way for anarchists to distribute literature, socialize, and talk about politics and strategy. They are now happening all over the world and with increasing frequency!

Over the last decade or so, book fairs have become an increasingly important way for anarchists to distribute literature, socialize, and talk about politics and strategy. They are now happening all over the world and with increasing frequency!