Posted on March 6th, 2015 in Events

We’re pleased to have our books represented by the local IWW branch at the first-ever Scranton Radical Book Fair!

Find more information at http://scrantonradicalbookfair.weebly.com/

And on Facebook here: http://www.facebook.com/events/610447519088829

Posted on March 6th, 2015 in Events

AK Press tables and authors, exact schedule TBA

INCITE! Color of Violence 4 Conference—Beyond the State: Inciting Transformative Possibilities

More information at: http://www.colorofviolence.org/

Posted on March 6th, 2015 in Events

AK Press tables and authors at the North American Anarchist Studies Network conference—exact schedule TBA.

Visit http://www.naasn.org/ for more information.

Facebook event here: http://www.facebook.com/events/1542313739386740/

Posted on March 6th, 2015 in Events

Find AK Press books and more at the Red Emma’s book tables!

More information: http://jewishvoiceforpeace.org/

Posted on March 6th, 2015 in Events

Stop by the book fair and find a selection of AK Press books at the Espacio 1839 table!

More information: http://www.facebook.com/events/896726250409454/

Posted on February 26th, 2015 in About AK, AK Allies, AK News

We’re working on something. It won’t be out until spring of 2016, but we’ll be giving you updates between now and then. Because, y’know, we’re excited.

We’re working on something. It won’t be out until spring of 2016, but we’ll be giving you updates between now and then. Because, y’know, we’re excited.

The book is Keywords for Radicals: A Late Capitalist Vocabulary of Culture and Society. For those of you who know Raymond Williams’ classic Keywords, the title may be self-explanatory. It’s basically a series of historical and analytic entries about words (each authored by a different contributor) whose meanings and usage are contested within radical circles. But whether or not you get the reference—and this project is, of course, very different than Williams’—we interviewed one of the book’s editors, Kelly Fritsch, to get an overview of the project. Read on, and when you’re done, checkout the book’s website, which has more info, and a list of the book’s amazing contibutors (who include, to name just a few, Silvia Federici, Ilan Pappé, Joy James, Franco “Bifo” Berardi, and John Bellamy Foster).

——————————

AK Press: Let’s start with the title. “Keywords” obviously references Raymond Williams’ seminal book, which was published almost forty years ago. Could you talk a bit about that book for people who may not have read it, and also about what you found inspiring (or inadequate, I suppose) about it?

Kelly Fritsch: Raymond Williams was one of the founding figures of what we now refer to as cultural materialism. He wrote Keywords in the period following the Second World War in response to the transformations he observed taking place within English-language word usage and meaning. In his estimation, these changes in word usage and meaning could be viewed as an index of the broader transformations that were happening within capitalist social relations. When considered together as a “vocabulary” of culture and society, Williams imagined that the keywords he had assembled—words like “individual” and “violence” but especially “culture”— could be read like a map of the social contradictions marking this period of change.

With Keywords for Radicals, we sought to draw upon this legacy while extending it in a few important ways. The first of these was that, while Williams was interested in capitalist dynamics during the postwar period, we felt it was important to try to come to terms with the significant transformations that have marked the era of late capitalism. The second major difference between the two projects is that, whereas Williams conceived of his vocabulary in fairly broad terms, we felt that it was important to delimit the scope of our investigation to focus on the contests over word usage and meaning that regularly erupt within the radical left. While these contests often emerge around particular issues, they also symptomatically reveal some of the more general attributes of today’s radical left, as well as of society more generally. Finally, whereas Williams authored every entry in Keywords, we felt that assembling a multi-author collection would be both a great challenge and a great opportunity.

How did the three of you come together on this project?

Clare O’Connor and AK Thompson approached me to work on Keywords for Radicals shortly after the three of us resigned from the Editorial Committee of Upping the Anti: A Journal of Theory and Action at the beginning of 2012. We had worked generatively together on that project for several years and were all very committed to its political and intellectual mandate, which was to create a non-sectarian space outside of—but in dialogue with—the movements in which we participated. This work was important to us because we found that immersion in struggle could sometimes constrain our capacity to critically assess our ideas and actions. With our writers and in our pages, we sought to constitute a political “we”—not by asserting a party line but, instead, through a careful analysis of our collective shortcomings. We left Upping the Anti for different reasons, but we all felt the need to continue its vision in some form.

Around that time, AK Thompson had been politically engaging the importance of concepts and the work they do—a preoccupation that dated back to the publication of Black Bloc, White Riot, where he dissected the contradictions at work in radical claims about “community.” These discussions subsequently informed Clare O’Connor’s critique of how radicals mobilized the concept during the Toronto G20 Summit in 2010. Meanwhile, as Editors of Upping the Anti, we regularly found ourselves reading drafts in which word usage and meaning seemed very slippery; as a result, we frequently found ourselves in lengthy discussions about this problem in editorial meetings, noting the contradictory and conflicting transformations that were taking place right before us. When Clare and AK first approached me about making struggles around word usage and meaning the subject of a political intervention, I said yes without hesitation.

These keywords are “for radicals.” Why do we need them, and furthermore, need to understand the historical evolution of their usage?

When we began working on this project, we quickly became aware of how many other radicals were working on word-based projects. Of these, perhaps the most significant were the short-lived Lexicon pamphlet series put out by the Institute for Anarchist Studies and CrimethInc’s Contra-dictionary. Although very different in their purpose and orientation, both of these projects helped to make clear how important language had become as a field of struggle for contemporary radicals. In the case of the IAS project, the objective aimed at reasserting what they called “definitional understandings” of words like power, gender, and colonialism. In contrast, CrimethInc conceived their project primarily in deconstructive terms, with each entry essentially cannibalizing common-sense associations and static definitions. For example, the Contra-dictionary entry on “Gender” in Days of War, Nights of Love ends with the following declaration: “There is no male. There is no female. Get free. Get off the map.”

In contrast to both of these approaches, we sought neither to reveal what words “actually” mean nor to highlight the limits of commonsense as though such limits were a problem of individual conceptualization. Instead, we wanted to encourage an engagement with words that used the conflicts within them to point toward broader social and historical tensions and implications. To put it another way, the book engages with contested words in order to illuminate a much broader field of contradictions that extends beyond the words themselves. Developing such an awareness can help to make us more compassionate toward one another as we struggle against all odds to communicate meaning clearly; however, it can also help us to clarify what our political options are, since—as Raymond Williams noted—sometimes the tensions within a word mark actual alternatives through which “problems of belief and affiliation are contested.” When illuminated, the historical developments within a word’s usage and meaning point to this broader field of political options and alternatives. Choosing a meaning always implicitly means siding with one developmental trajectory over another. In our view, it is always better that this process be conscious and deliberate, and that the choice be explicit. (more…)

Posted on January 14th, 2015 in Uncategorized

Helene Minkin’s memoir, translated by Alisa Braun and edited/introduced by Tom Goyens, is at the printer. We’re excited about this one. This is the first time Minkin’s words, which provide a unique perspective on late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century anarchism in the US, have been available in English. She forces us to reassess many of our ideas about some of the movement’s major figures. You’ll have to get the book to see how (go here to pre-order), but in the meantime here’s a snippet from Tom Goyens’s Introduction. Enjoy!

Helene Minkin’s memoir, translated by Alisa Braun and edited/introduced by Tom Goyens, is at the printer. We’re excited about this one. This is the first time Minkin’s words, which provide a unique perspective on late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century anarchism in the US, have been available in English. She forces us to reassess many of our ideas about some of the movement’s major figures. You’ll have to get the book to see how (go here to pre-order), but in the meantime here’s a snippet from Tom Goyens’s Introduction. Enjoy!

*****

By the time Minkin arrived in New York in June 1888, this Yiddish- speaking movement had grown and there was talk of launching a publishing venture of their own. The Pioneers of Liberty made such an announcement in January 1889, and a month later the first issue of Varhayt (Truth) appeared—the first Yiddish anarchist periodical in the United States.[13] Jewish comrades could read articles by Kropotkin and of course Most, and educate themselves about the Paris Commune and American labor news. The venture ended after five months due to lack of funds, but was soon followed by another paper, the Fraye Arbeter Shtime, one of the longest-lasting anarchist papers in history as it turned out. An entire subculture emerged modeled on what the Germans had built. Jewish anarchists set up cooperatives, mutual aid organizations, and clubs, and they staged concerts and theater performances. They were especially conspicuous as a voice for atheism and anticlerical agitation, something that made Most feel right at home. In fact, it was one of Most’s most widely read pamphlets, The God Pestilence, translated into Yiddish in 1888, that inspired and energized much of this activism. Most shocking to traditional Jews was the annual Yom Kippur ball organized by anarchists, which made a mockery out of Judaism’s holiest day of the year.

Minkin, then, witnessed upon her arrival a mature, diverse, and vibrant—if dejected after Haymarket—anarchist movement, predominantly German with a growing Jewish contingent. A movement alive with weekly meetings, large commemorative gatherings, festive fundraisers, outings, and reading clubs. Pamphlets, books, and anarchist newspapers were readily available by subscription or at various beerhalls and restaurants. This movement was also male-dominated despite the fact that some German activists championed women’s rights. Women were by no means absent; every press account of large anarchist gatherings noted the impressive attendance by women. But most club members were men, and while reliable sources are rare, it seems that most German anarchist families retained traditional gender roles within the household. Occasionally, anarchist papers in their event announcements encouraged women to participate more fully.[14] But elsewhere in a paper like Freiheit, gendered language was not uncommon, and on one occasion, in March 1887, a woman complained about the insulting tone and promptly received an apology.[15]

When Most and Minkin began a relationship and started a family, the anarchists loyal to Most expressed their disapproval, as Minkin relates in her memoir. Implicit in this backlash was an assumption that family life for movement members impeded the cause of revolution, softened the (male) activist, and would likely result in trouble. It may also drain resources away from the movement’s activities, they feared. One dramatic incident—if perhaps not wholly representative—illustrates this dynamic. On January 28, 1902, comrade Hugo Mohr was found dead in his Paterson, NJ apartment; he had gassed himself out of fear of a second arrest after he had been released on bail that day. According to a court reporter for the New York Sun, no friend of anarchists, Mohr had been charged with “cruelty to his family.” He had been out of work for a year, “took the money that his wife and oldest daughter earned and bought Anarchist literature with it.” He also donated money to Most’s defense fund by sending it to Helene Most who was managing the paper. The reporter added that “he beat his wife and children until they were afraid of their lives. Last Tuesday night he caught his oldest daughter by the ear and nearly tore it off.”[16] Remarkably, Freiheit, in a brief notice chose to blame Mohr’s death on his wife: “Comrade Mohr has committed suicide by gas in Paterson. An evil woman drove him to his death. That’s how they are.”[17]

Emma Goldman, who arrived in New York in August 1889, was especially attuned to the politics of gender and sexuality. She had recently ended a brief and unhappy marriage, and was bent on maintaining her independence and rebelliousness. If the German movement, and Most especially, provided her a foot in the door, she nonetheless became disillusioned with their outdated ideas around gender. “I expressed contempt,” she wrote, “for the reactionary attitude of our German comrades on these matters.”[18] And again, in 1929, in a letter to Berkman, she charged that “[the Germans] remain stationary on all points except economics. Especially as regards women, they are really antediluvian.”[19]

Johann Most’s views on women and gender fit Goldman’s description perfectly. And she would know. It was in fact Goldman’s brief but intimate relationship with her mentor Most that confirmed for her the underlying conservatism of many male activists. What Most sought in the relationship was domestic comfort and security with an assumption that she would provide it. Goldman would not, and she told him as much. Moreover, she would from now on judge herself superior as a woman activist to her roommate Helene Minkin who accepted, to some extent, a domestic role with Most. As Goldman wrote in her memoir with a hint of disdain: “A home, children, the care and attention ordinary women can give, who have no other interest in life but the man they love and the children they bear him—that was what he needed and felt he had found in Helen.”[20] But in a 1904 letter to Berkman, her tone is much harsher. “Helena M. is a common ordinary Woman, has not developed in the least,” she wrote. “I am sorry to say, that all those of my sex we have known together [the Minkin sisters] have become ordinary Haustiere [pets] und Flatpflanzen [potted plants].”[21]

[…]

Contrary to Goldman’s comment, however, Helene Minkin did have other interests in life, and there were times she too resented housework. She was certainly more than a domestic sidekick of the famed Johann Most. She was a committed anarchist in her own right and believed deeply in the cause for freedom and workers’ rights. She did not share the uncompromising vision of a Berkman who modeled himself after the unswerving Russian revolutionaries. She did not have the talent for forceful public speaking like Most or Goldman. She did have a talent for writing, management, and editing. After she and Most moved in together, Minkin became active in the running of Freiheit, Most’s paper that made its way to readers since 1879. And so perhaps their relationship offered, for both, a workable balance between family and work. Especially during the late 1890s when the paper nearly died, Minkin was crucial in keeping it afloat while many of the (mostly male) comrades failed to step up. At one point, Most was ready to quit and burn all the books.[30] “Of the few who stood faithfully beside him [Most] during these tough months,” wrote biographer Rudolf Rocker, “his brave life partner Helene Most deserves special mention because time and again she helped him to keep up his work, and she took care of almost the entire expedition of the paper.”[31]

NOTES

12 Quoted in Paul Avrich, “Jewish Anarchism in the United States,” Anarchist Portraits (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1988), 178.

13 Ibid., 179.

14 Freiheit, October 25, 1884 and June 25, 1892.

15 Freiheit, March 2, 1889. The editors had used the slur “old hags” (alte Weiber).

16 “Anarchist End His Life. Mohr Taught His Children to Anathematize the Dead President,” New York Sun, January 29, 1902. See also “Killed Himself, Cheated Police,” New York Evening World, January 28, 1902.

17 Freiheit, February 1, 1902. Originally: “Genosse Mohr hat zu Paterson per Gas Selbstmord verübt. Ein böses Weib hat ihn in den Tod gejagt. So sinn’ se.”

18 Goldman, Living My Life, vol. 1, 151.

19 Goldman to Berkman, St. Tropez (France), February 20, 1929, in Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman, Nowhere at Home: Letters from Exile of Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman, eds. Richard Drinnon and Anna Maria Drinnon (New York: Schocken Books, 1975), 145.

20 Goldman, Living My Life, vol. 1, 77. Italics added.

[…]

30 Minkin, “An die Leser der ‘volume,” Freiheit, April 21, 1906.

31 Rudolf Rocker, Johann Most: Das Leben eines Rebellen (Berlin: “Der Syndikalist”, 1924; Glashütten im Taunus: Detlov Auvermann, 1973), 387.

Posted on January 8th, 2015 in Uncategorized

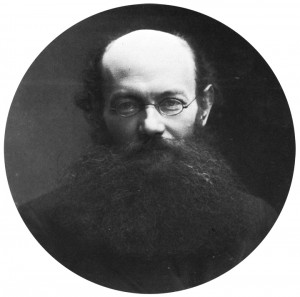

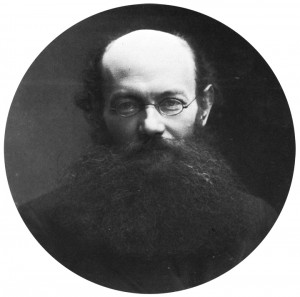

On this day in 1883, the trial of over sixty anarchists began in Lyon, France. The state rounded them up and charged them with reconstructing the French branch of the International Working Men’s Association, which had been outlawed the year before (in the aftermath of the Paris Commune). For their part, the accused used the opportunity to further spread their ideas. The trial, as Kropotkin later put it in his Memoirs of a Revolutionist, “during which all the accused took a very firm attitude, preaching our doctrines for a fortnight — had a powerful influence in clearing away false ideas about anarchism in France, and surely contributed to some extent to the revival of socialism in other countries… The contest between the accusers and ourselves was won by us, in the public opinion.”

On this day in 1883, the trial of over sixty anarchists began in Lyon, France. The state rounded them up and charged them with reconstructing the French branch of the International Working Men’s Association, which had been outlawed the year before (in the aftermath of the Paris Commune). For their part, the accused used the opportunity to further spread their ideas. The trial, as Kropotkin later put it in his Memoirs of a Revolutionist, “during which all the accused took a very firm attitude, preaching our doctrines for a fortnight — had a powerful influence in clearing away false ideas about anarchism in France, and surely contributed to some extent to the revival of socialism in other countries… The contest between the accusers and ourselves was won by us, in the public opinion.”

Below is the declaration the anarchists made in their defense. You can find it, excerpts from Kropotkin’s own defense speech, and about 650 additional pages of Kropotkin’s words in our book Direct Struggle Against Capital: A Peter Kropotkin Anthology, edited by Iain McKay

—

DEFENCE DECLARATION

What anarchism is, and what anarchists are, we shall try to explain: Anarchists, gentlemen, are citizens who, in an age when freedom of opinion is preached everywhere, have believed it to be their duty to call for unlimited freedom.

Yes, gentlemen, we are some thousand, some millions of workers, all over the world, who demand absolute freedom, nothing but freedom, the whole of freedom!

We want freedom—that is to say, we claim for every human being the right and the means to do whatever he pleases and only what he pleases, and to satisfy all his needs without any limit other than natural impossibilities and the needs of his neighbours, to be respected equally.

We want freedom, and we believe its existence to be incompatible with the existence of any kind of authority, whatever its origin and form may be, whether it is elected or imposed, monarchist or republican, whether it is inspired by divine right or by popular right, by holy oil [1] or by universal suffrage.

History is there to teach us that all governments are alike and equal. The best are the worst. There is more cynicism in some, more hypocrisy in others. In the end there is always the same behaviour, always the same intolerance. Even the most apparently liberal have in reserve, beneath the dust of legislative files, some nice little law on the International for use against troublesome opponents.

The evil, in other words, in the eyes of anarchists does not lie in one form of government rather than another. It lies in the governmental idea itself, it lies in the principle of authority.

In short, the substitution in human relationships of a free contract which can be revised or cancelled in perpetuity, for administrative and legal tutelage, for imposed discipline—that is our ideal.

Anarchists therefore intend to teach the people to do without government, just as they are beginning to learn to do without God.

The people will similarly learn to do without property owners. The worst of tyrants, after all, is not the one who imprisons you but the one who starves you, not the one who holds on to your collar but the one who tightens up your belt.

There can be no liberty without equality. There is no liberty in a society where capital is monopolised in the hands of a minority which is growing smaller every day, and where nothing is shared equally—not even public education, although it is paid for by the contributions of all.

We believe that capital—the common inheritance of mankind, since it is the fruit of the co-operation of past and present generations—must be at the disposal of all in such a way that none may be excluded, and that in turn no one may get possession of a part to the detriment of the rest.

In a word, we want equality—real equality, as a corollary or rather as a prior condition of liberty. From each according to his abilities, to each according to his needs—that is what we sincerely and strenuously desire. That is what will come about, for no regulation can prevail against claims which are at the same time legitimate and necessary. That is why you want to condemn us to all kinds of hardship.

Scoundrels that we are, we demand bread for everyone, work for everyone, and for everyone independence and justice too!

———

1 Literally, the Holy Ampule (Sainte-Ampoule). This was a glass vial which held the anointing oil for the coronation of the kings of France. Its first recorded use was by Pope Innocent II for the anointing of Louis VII in 1131. (Editor)

Posted on January 5th, 2015 in AK Book Excerpts

Underground Passages: Anarchist Resistance Culture, 1848–2011 is on its way back from the printer. We’re waiting expectantly, as are many of you, we know. Not sure whether it will take some of the edge off the anticipation or fill you with even more longing, but here’s a hefty excerpt from the Introduction (oh, and if you pre-order the book here http://www.akpress.org/underground-passages.html, we’ll ship it out to you are soon as it arrives in the warehouse).

Underground Passages: Anarchist Resistance Culture, 1848–2011 is on its way back from the printer. We’re waiting expectantly, as are many of you, we know. Not sure whether it will take some of the edge off the anticipation or fill you with even more longing, but here’s a hefty excerpt from the Introduction (oh, and if you pre-order the book here http://www.akpress.org/underground-passages.html, we’ll ship it out to you are soon as it arrives in the warehouse).

FROM THE INTRODUCTION…

Since “an anarchist could not live a consistent life in America” or anywhere else where conditions of statism and capitalism prevailed, and insofar as the hallmark of anarchist ethics is the refusal to distinguish between ends and means or principles and practices, to be an anarchist is almost always to live in an intolerable moral bind.[30] As the anarcho-communist Luigi Galleani (1861– 1931) put it: “By accepting a wage, by paying rent for a house, we, with all our proclaimed revolutionary and anarchist aspirations, recognize and legitimate capital … in the most tangible and painful way.”[31] The individualist anarchist Albert Libertad (1875–1908) perhaps stated the problem most forcefully in his declaration that “Every day we commit suicide partially”:

I commit suicide when I devote, to hours of absorbing work, an amount of energy which I am not able to recapture, or when I engage in work which I know to be useless….

I commit suicide whenever I consent to obey oppressive men or measures.

I commit suicide whenever I convey to another individual, by the act of voting, the right to govern me for four years….

Complete suicide is nothing but the final act of total inability to react against the environment.

These acts, of which I have spoken of as partial suicides, are not therefore less truly suicidal. It is because I lack the power to react against society, that I inhabit a place without light and air, that I do not eat in accordance with my hunger or my taste, that I am a soldier or a voter, that I subject my love to laws or to compulsion.[32]

At every turn, the anarchist is compelled to endorse a universe of values that is the antithesis of her own, to cancel herself out—a kind of ongoing moral suicide.

Anarchists…are of course not the only people to suffer such alienation, which is to some extent the common fate of all who are marked as marginal or radical. What is unique about our case is not only the extent of our disagreement with the world as it is given to us (defining our being by way of a longer list of things-to-be-against) but its unmediated intensity. For a Marxist, for instance, the desire for another world, however palpable, is supposed to be subject to the dialectic of history: capitalism will die of its own contradictions. No such consolation is available for anarchists—not even, as is often asserted, the consolation of a pure “human nature” that is bound to shine forth again once the dross of history is washed away.[33] On the contrary, this romantic myth is vigorously denied by every major statement of anarchist theory, beginning with the excoriation of Rousseau by Proudhon and Bakunin alike.[34] It is no more a question of substituting biology for history than it is of substituting history for morality. The moral question—how to live?—is left quite bare, and confronts us in all its force.

The main body of the cultural production to emerge from the anarchist movements of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, I contend, can best be understood as a response to this question—not quite a “solution” or an “answer” so much as a way of living with the problem for as long as it lasts, a means of inhabiting history until it stops hurting. Anarchists practice culture as a means of mental and moral survival in a world from which they are fundamentally alienated. Stated positively—well, it is hard to do better than the anarchist poet Kaneko Mitsuharu (1895–1975): “To oppose is to live. / To oppose is to get a grip on the very self.”[35]

This immediately risks being mistaken for some other kind of theory about the relation between anarchist politics and anarchist culture. One of these is the notion of cultural rebellion as a substitute for the political kind. David Weir, for instance, argues that we can read the history of anarchism as follows: whereas anarchists were on the losing side of every revolution from 1871 to 1939, their politics translated nicely into the aesthetic realm, where it came to mean a kind of individualist stance, a willful refusal to make sense to a mass audience—in other words, what came to be known simply as “modernism.” In short, Weir suggests, “anarchism succeeded culturally where it failed politically.”[36] Of course, the same half-full glass might look completely empty if viewed from a slightly more politically engaged perspective than Weir’s. Even if anarchist impulses might be said to have migrated successfully into the domain of art, and even if they produced there practices that resisted the capitalist imperative to produce mass-market cultural commodities, this still amounted to a kind of capitalism-by-other-means, a contest for the “accumulation of symbolic capital,” which could later be traded in for the economic variety, making modern art into a kind of luxury good that would testify to the owner’s social status.[37] Whether or not these modernist works eschewed symbolism entirely—even an ultra-abstractionist work such as Kasimir Malevich’s Black Square became a kind of symbol of the artist’s supreme will not to symbolize—they also ran the risk of becoming privatized surrogates for political refusal, something one turned to in place of collective action, a “compensation and palliative,” as John Zerzan (b. 1943) bluntly puts it, for what cannot be realized in “life.”[38]

This is all as may be. However, the kind of anarchist-inspired cultural production that formed the kernel of modernism—the Cubist abstractions of a Pablo Picasso or the conceptual music of a John Cage, for instance—was never very deeply embedded in any real community of anarchists. It was never firmly connected to an anarcho-syndicalist organization such as the Confederación Nacional de Trabajo (CNT) or the revolutionary syndicalist Industrial Workers of the World (IWW),[39] for instance, which sponsored and produced very different forms of art, e.g., the strikingly symbolic mass poster art of Manuel Monleón Burgos (1904–1976) or the satirical folk songs of Joe Hill (1879–1915). The modernist aesthetic studied by Weir and others, in its rejection of representation and narrative, actually has little in common with the aesthetics favored by most anarchists. The demands made on art by the residents of a bohemia, however politicized they may have been at times, were not quite the same as those made by the broader constituencies of what was, at its height, an international working-class movement.[40]

What anarchists did demand from art, by and large, was what they demanded from all the forms and moments of their political lives: i.e., that it should, as much as possible, embody the idea in the act, the principle in the practice, the end in the means. If anarchism is “prefigurative politics,” striving to make the desired future visible in and through one’s actions in the present, then anarchist resistance culture had to somehow prefigure a world of freedom and equality.

The sociologist Howard J. Ehrlich offers us what could be a helpful handle on this notion of anarchist culture as prefigurative when he speaks of a “revolutionary transfer culture,” i.e., “that agglomeration of ideas and practices that guide people in making the trip from the society here to the good society there in the future.”[41] The metaphor of “transfer” is misleading, however, if it makes us imagine this process as something too easy; in the age of globalization, after all, a “trip” is inevitably only a matter of hours at most. Particularly during periods of intense repression, committed anarchists were not always convinced that rapid change was imminent: “Not for a hundred, not for five hundred years, perhaps, will the principles of anarchy triumph,” Emma Goldman (1869–1940) surmised.[42] Nor was the revolution she wanted only a matter of overthrowing the State or abolishing Capital; a “transvaluation not only of social, but also of human values,” encompassing “every phase of life,—individual, as well as the collective; the internal, as well as the external phases,” was not necessarily to be imagined on the Jacobin model of a single, swift transformation.[43] Traveling, movement, mobility are all appropriate images, except insofar as they foreground the endpoint, the destino. While anarchists generally think of their aspirations in terms of “revolution,” the journey—“walk[ing] toward anarchy,” as Errico Malatesta (1853–1932) put it—is at least as important as the goal.[44]

How could anarchists maintain such a pitch of activity, such an optimism of the will, in the face of such pessimism of the intellect? As prefigurative politics, anarchism can entail a paradoxically pessimistic attitude toward the possibility of arriving at a revolutionary moment: a certain historical amor fati or “anarcho-fatalism.” Francis Dupuis-Déri notes precisely such an indifference toward “the revolution” as event among contemporary anarchist activists. Instead of deferring desires into a utopian future seen as imminent, anarchist activists seek to make their desires as immanent as possible—to demand more from their relationships, from the process of political activity, from their everyday lives.[45] While Dupuis-Déri attributes contemporary anarcho-fatalism in part to a realistic reckoning of the poor prospects for a classical “revolution” in the relatively affluent and stable global North, such an orientation is hardly a recent phenomenon; we find it clearly and forcefully theorized in the writings of Gustav Landauer (1870–1919), anarchist martyr of the abortive German revolution of 1919.

In Die Revolution, written in 1911 and reissued on the eve of the actual event itself, Landauer took up Proudhon’s suggestion that “there is a permanent revolution in history,” reinterpreting history in terms of a continuity of revolutionary energies—sometimes forced “underground,” at other times erupting into the open air.[46] In this interpretation, revolution becomes not a historically and geographically isolated event but a more nebulous process that only occasionally condenses into decisive moments—“evolution preceding revolution,” as Elisée Reclus put it, “and revolution preceding a new evolution, which is in turn the mother of future revolutions.”[47] This takes the logic of revolution far from the scientific pretensions of historical materialism. Indeed, where Marx rebuked Bakunin for looking to “willpower” and not “economic conditions” as the source of revolution, for Landauer, it is precisely will and desire, social emotions, that are the primary revolutionary forces: revolution is “possible at all times, if enough people want it”:[48]

Little is to be expected from external conditions, and people think too much about the environment, the future, the others, separating means and ends too much, as if an end could be attained in this way. Too often you think that if the end is glorious, dubious means must also be justified. But only the moment exists for us; do not sacrifice the reality to the chimera! If you seek the right life, live it now; you make it difficult by seeking it outside yourselves, in the future, and for the sake of this beautiful future you fill your present with ugliness…. If the glory and the kingdom of God on earth should ever come for the world, for the masses, for people and nations, can it come in any way other than by the fact that one immediately begins to do what is right?[49]

If we can await nothing from “external conditions,” we must demand everything from ourselves, from within. This inward turn, however, is not to be understood as a subjective substitute for social action (like one of the “revolutions from within” peddled by pop psychologists); it is a fully social and material attempt to come to grips with the world. Like Gatti’s tunnel, it is a “line of flight”—“not a leap into another realm,” Todd May explains, but “a production within the realm of that from which it takes flight.”[50] In short, this is a matter of resistance, of finding ways, “at every instant,” to “withdraw from injustice.”[51] In the words of Landauer’s essay, “Durch Absonderung zur Gemeinschaft [Through Separation to Community],” it is out of a profound sense of responsibility to others that anarchists seek “to leave these people,” to keep “our own company and our own lives”; “Away from the state, as far as we can get! Away from goods and commerce! Away from the philistines! Let us … form a small community in joy and activity.”[52] Landauer’s conception of anarchism as exodus, striving toward “community” precisely “through separation,” illuminates the purpose of anarchist resistance culture: to enable us, while remaining within the world of domination and hierarchy, to escape from it.

Something like Ehrlich‘s “transfer culture” or Landauer’s “community through separation” is carried by the Italian Autonomists’ concept of “exodus.” Exodus, a process of “engaged withdrawal” from authoritarian institutions, which is at the same time the “founding” of a new community, was partly inspired by observations of U.S. black nationalism, which used the image of the passage out of Egypt “to change circumstances without [anyone] shifting one millimetre in space.”[53] Indeed, from the perspective of exodus, the question of whether the emancipated future is imminent or remote is beside the point:

The motivating force of the sticking together and the unity— the “being together”—of that group that was on its way (“in movement”) toward the Promised Land, toward the collective dimension of its own emancipation, was probably more the unidimensionality of the desert, its immobility and immutability, than any hopes for the approach of some eventual future goal.[54]

Anarchist resistance culture is a way of living in transit through this desert. The resistance culture of the anti-apartheid movement had not only a specific target but a destino, a Promised Land, an end. Anarchist resistance is not mainly defined by its end; it is a middle, a means.

It is a tunnel.

NOTES

30 Blaine McKinley, “‘The Quagmires of Necessity’: American Anarchists and Dilemmas of Vocation,” American Quarterly 34.5 (Winter 1982): 507.

31 Luigi Galleani, The Principle of Organization, trans. Wolfi Landstreicher (Cascadia: Pirate Press Portland, 2006), 4. In a contemporary echo, Laura Portwood-Stacer observes that among anarchists today, “everyone can be called out at some point for not living up to anarchist principles,” since— no less than 1925—“to live in contemporary society is to be complicit with capitalism and other forms of exploitation” (130).

32 Albert Libertad, “The Joy of Life,” in Man! An Anthology of Anarchist Ideas, Essays, Poetry and Commentaries, ed. Marcus Graham (London: Cienfuegos Press, 1974), 355–356. Cf. Alexandra Myrial (a.k.a. Alexandra David-Néel, 1868–1969), in Pour la Vie (1901): “Obedience is death. Each instant man submits to an alien will is an instant cut off from his life” (13).

33 The notion that anarchists were anarchists because they believed in the existence of a good human nature, repressed by social institutions such as the State, that merely awaited expression, is really a durable misreading that survives in spite of many concerted attempts to puncture it, perpetuated by political scientists, philosophers, and historians alike. See, for instance, Dave Morland’s “Anarchism, Human Nature and History: Lessons for the Future” (in Twenty-First Century Anarchism, eds. Jon Purkis and James Bowen [UK: Cassell, 1997], 8–23), David Hartley’s “Communitarian Anarchism and Human Nature” (in Anarchist Studies 3.2 [1995]: 145–164), and my own Anarchism and the Crisis of Representation: Hermeneutics, Aesthetics, Politics (Selinsgrove, PA: Susquehanna University Press, 2006), 56–60.

34 See, for instance, the ridicule heaped by Proudhon on Rousseau’s notion that “Man is born good … but society … depraves him” (System of Economic Contradictions: or, the Philosophy of Misery, trans. Benjamin R. Tucker [Boston: Benjamin R. Tucker, 1888], 404), or Bakunin’s contempt for Rousseau’s conception of “primitive men enjoying absolute liberty only in isolation” (Bakunin on Anarchism, 128).

35 Kaneko Mitsuharu, “Opposition,” trans. Geoffrey Bownas and Anthony Thwaite, in 99 Poems in Translation: An Anthology, ed. Harold Pinter et al. (New York: Grove Press, 1994), 54–55.

36 David Weir, Anarchy and Culture: The Aesthetic Politics of Modernism (Massachusetts: University of Massachusetts, 1997), 5.

37 Pierre Bourdieu, The Field of Cultural Production: Essays on Art and Literature, trans. Randal Johnson (New York: Columbia University Press, 1993), 75.

38 John Zerzan, Elements of Refusal (Seattle: Left Bank Books, 1988), 56.

39 The term “revolutionary syndicalism” refers to the radical movement emerging in the 1890s, eclectic as to ideology but firmly internationalist and anti-statist (and harboring a substantial faction of self-defined anarchists), that saw direct action and self-organization through unions (in French, syndicats) as the means proper to workers’ emancipation. The origins of the term “anarcho-syndicalism” (and its cognates) are somewhat cloudy, but it appears to have come into use in the early 1920s, first as an epithet hurled by Communist Party members at syndicalists who resisted the assimilation of their movement, then as a self-description adopted by some of those same syndicalists (David Berry, A History of the French Anarchist Movement, 1917–1945 (Oakland, CA: AK Press, 2009), 152; Mintz,“Guión provisional sobre el anarcosindicalismo,” El Solidario 14 [Fall 2008]: xii–xiii). Anarcho-syndicalists specifically defined the emancipatory goal of revolutionary syndicalism as anarchy (or, in the formulation of the CNT, “libertarian communism”).

40 For a somewhat contrary view, see Allan Antliff ’s Anarchist Modernism: Art, Politics, and the First American Avant-Garde (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001).

41 Howard J. Ehrlich, “How to Get from Here to There: Building Revolutionary Transfer Culture,” in Reinventing Anarchy, Again, ed. Howard J. Ehrlich (Edinburgh: AK Press, 1996), 329.

42 Qtd. in Michelson “A Character Study of Emma Goldman,” Emma Goldman: A Documentary History of the American Years, Vol. 1, ed. Candace Falk (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003), 441.

43 Emma Goldman, My Disillusionment in Russia (Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 2003), 259; and Anarchism and Other Essays (New York: Mother Earth Publishing Association, 1910), 56. Similarly, Ruth Kinna has argued that recent poststructuralist interpreters of the anarchist tradition misread Kropotkin’s conception of revolution: “It was not a matter of going to sleep in a statist system one night and waking up in utopia the next morning. Kropotkin believed that revolution was necessary, but it was work in progress as much as a cataclysmic event” (82).

44 Errico Malatesta, “Towards Anarchism,” in Anarchism: A Documentary History of Libertarian Ideas, Vol. 1, ed. Robert Graham (Montréal: Black Rose Books, 2005), 506.

45 Francis Dupuis-Déri, “En deuil de révolution? Pensées et pratiques anarcho-fatalistes.” Réfractions 13 (Automne 2004): 139–150.

46 Proudhon, Oeuvres complètes 17 (Paris: Librairie Internationale, 1868), 142; Landauer, Revolution, 116, 154.

47 Elisée Reclus, “Evolution, Revolution, and the Anarchist Ideal,” in Anarchy, Geography, Modernity: The Radical Social Thought of Elisée Reclus, eds. and trans. John Clark and Camille Martin (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2004), 153.

48 Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, Collected Works Vol. 24: Marx and Engels, 1874–83 (London: Lawrence & Wishart, 1989), 518; Gustav Landauer, For Socialism, trans. David J. Parent (St. Louis, MO: Telos Press, 1978), 74.

49 Gustav Landauer, Der Werdende Mensch: Aufsätze über Leben und Schrifttum, ed. Martin Buber (Potsdam: G. Kiepenheuer, 1921), 228.

50 Todd May, Gilles Deleuze: An Introduction (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 128.

51 Landauer, Der Werdende Mensch, 228, trans. and emphasis mine.

52 Landauer, Revolution, 94–108.

53 Paolo Virno, “Virtuosity and Revolution: The Political Theory of Exodus,” trans. Ed Emory, in Radical Thought in Italy: A Potential Politics, eds. Michael Hardt and Paolo Virno (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1996), 196; Andrea Colombo qtd. in Steve Wright, “Confronting the Crisis of ‘Fordism’: Italian Debates Around Social Transition,” http:// www.arpnet.it/chaos/steve.htm.

54 Marco Revelli, “Worker Identity in the Factory Desert,” trans. Ed Emory, in Radical Thought in Italy, 118–119. This also recalls Walter Benjamin’s concluding remarks in “Theses on the Philosophy of History”: “We know that the Jews were prohibited from investigating the future…. This does not imply, however, that for the Jews the future turned into homogeneous, empty time. For every second of time was the strait gate through which the Messiah might enter” (Walter Benjamin, Illuminations: Essays and Reflections, trans. Harry Zohn and ed. Hannah Arendt [New York: Schocken Books, 1969], 264).

Posted on December 18th, 2014 in Recommended Reading

A hundred and twenty years ago this week, Voltarine de Cleyre gave the following impassioned speech at a benefit concert for Emma Goldman and others who had been arrested the previous August at a demonstration. In the process, she makes an equally sharp argument in favor of expropriating the wealth of the ruling class.

In Defense of Emma Goldmann and the Right of Expropriation

by Voltairine De Cleyre

“A starving man has a natural right to his neighbor’s bread.” Cardinal Manning.

“I have no idea of petitioning for rights. Whatever the rights of the people are, they have a right to them, and none have a right to either withold or grant them.” Paine’s “Rights of Man”

“Ask for work; if they do not give you work ask for bread; if they do not give you work or bread then take bread.” Emma Goldmann.

Delivered in New York, Dec. 16. 1894.

The light is pleasant, is it not my friends? It is good to look into each other’s faces, to see the hands that clasp our own, to read the eyes that search our thoughts, to know what manner of lips give utterance to our pleasant greetings. It is good to be able to wink defiance at the Night, the cold, unseeing Night. How weird, how gruesome, how chilly it would be if I stood here in blackness, a shadow addressing shadows, in a house of blindness! Yet each would know that he was not alone; yet might we stretch hands and touch each other, and feel the warmth of human presence near. Yet might a sympathetic voice ring thro’ the darkness, quickening the dragging moments. — The lonely prisoners in the cells of Blackwell’s Island have neither light nor sound! The short day hurries across the sky, the short day still more shortened in the gloomy walls. The long chill night creeps up so early, weaving its sombre curtain before the imprisoned eyes. And thro’ the curtain comes no sympathizing voice, beyond the curtain lies the prison silence, beyond that the cheerless, uncommunicating land, and still beyond the icy, fretting river, black and menacing, ready to drown. A wall of night, a wall of stone, a wall of water! Thus has the great State of New York answered EMMA GOLDMANN; thus have the classes replied to the masses; thus do the rich respond to the poor; thus does the Institution of Property give its ultimatum to Hunger!

“Give us work” said EMMA GOLDMANN; “if you do not give us work, then give us bread; if you do not give us either work or bread then we shall take bread.”– It wasn’t a very wise remark to make to the State of New York, that is–Wealth and its watch-dogs, the Police. But I fear me much that the apostles of liberty, the fore-runners of revolt, have never been very wise. There is a record of a seditious person, who once upon a time went about with a few despised followers in Palestine, taking corn out of other people’s corn-fields; (on the Sabbath day, too). That same person, when he wished to ride into Jerusalem told his disciples to go forward to where they would find a young colt tied, to unloose it and bring it to him, and if any one interfered or said anything to them, were to say: “My master hath need of it”. That same person said: “Give to him that asketh of thee, and from him that taketh away thy goods ask them not back again”. That same person once stood before the hungry multitudes of Galilee and taught them, saying: “The Scribes and the Pharisees sit in Moses’ seat; therefore whatever they bid you observe, that observe and do. But do not ye after their works, for they say, and do not. For they bind heavy burdens, and grievous to be borne, and lay them on men’s shoulders; but they themselves will not move them with one of their fingers. But all their works they do to be seen of men; they make broad their phylacteries, and enlarge the borders of their garments: and love the uppermost rooms at feasts, and the chief seats in the synagogues, and greetings in the markets, and to be called of men, Rabbi, Rabbi’.” And turning to the scribes and the pharisees, he continued: “Woe unto you, Scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites! for ye devour widows’ houses, and for a presence make long prayers: therefore shall ye receive the greater damnation. Woe unto you, Scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites! for ye pay tithe of mint, and anise, and cummin, and have omitted the weightier matters of the law, judgment, and mercy, and faith: these ought ye to have done and not left the other undone. Ye blind guides, that strain at a gnat and swallow a camel! Woe unto you, Scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites! for ye make clean the outside of the cup end plaster, but within they are full of extortion and excess. Woe unto you, Scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites! For ye are like unto whited sepulchres, which indeed appear beautiful outward, but within are full of dead men’s bones and all uncleanness. Even so ye outwardly appear righteous unto men, but within ye are full of hypocrisy and iniquity. Woe unto you, Scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites! Because ye build the tombs of the prophets and garnish the sepulchres of the righteous; and say, ‘if we had been in the days of our fathers we would not have been partakers with them in the blood of the prophets’. Wherefore ye be witnesses unto yourselves that ye are the children of them which killed the prophets. Fill ye up then the measure of your fathers! Ye serpents! Ye generations of vipers! How can ye escape the damnation of hell!” (more…)