Posted on February 12th, 2010 in AK News

Hi folks,

We are happy to announce that there’s three new AK Press books at the printer right now. We sent them all off over the last few days and they will be trickling in in mid-March. So all those lucky Friends of AK subscribers will hit paydirt when their April shipment arrives.

First up is We Are an Image From the Future: The Greek Revolt of December 2008. It’s edited by A.G. Schwarz, Tasos Sagris, and the Void Network. Here’s what we say about it:

What causes a city, then a whole country, to explode? How did one neighborhood’s outrage over the tragic death of one teenager transform itself into a generalized insurrection against State and capital, paralyzing an entire nation for a month?

This is a book about the murder of fifteen-year-old Alexis Grigoropoulos, killed by the police in the Exarchia neighborhood of Athens on December 6th, 2008, and of the revolution in the streets that followed, bringing business as usual in Greece to a screeching, burning halt for three marvelous weeks, and putting the fear of history back into the bureaucrats of Fortress Europe and beyond.

We Are an Image From the Future delves into the December insurrection and its aftermath through interviews with those who witnessed and participated in it, alongside the communiqués and texts that circulated through the networks of revolt. It provides the on-the-ground facts needed to understand these historic events, and also dispels the myths activists outside of Greece have constructed around them. What emerges is not just the intensity of the riots, but the stories of organizing and solidarity, the questions of strategy and tactics: a desperately needed examination of the fabric of the Greek movements that made December possible.

“If protest is when I say I disagree and resistance is when I do something about it, then insurrection is when everyone else is on-board too. So it was in December of 2008, when Greece burned. Behind the spectacular street uprising is years of organizing and a deeply embedded anti-authoritarian culture of emancipation. We Are an Image from the Future is a quintessential portrait of revolution in action. The coming global insurrection has already begun.”—Ramor Ryan, author of Clandestines—The Pirate Journals of an Irish Exile.

“What the Zapatista uprising of 1994 was to the antiglobalization movement, the Greek uprising of 2008 could be to the demise of capitalism itself.”—CrimethInc. Ex-Workers’ Collective

“This book is just what Dr. Fucking Anarchy ordered. How to turn insurrection into revolution. The Greek revolt will inspire a generation as Paris ’68 did 40 years earlier.”—Ian Bone, class warrior and author of Bash the Rich

“This dazzling collection is not a book about the great insurrection of 2008—it is a living piece of it that can become a part of us, and through us, it opens the prospect of a universe we might never otherwise have imagined possible. Future historians may well conclude that the Revolution finally began in 2008. If they do, this book will have played a crucial role in that realization.”—David Graeber, author of Direct Action: An Ethnography

Cover design by Kate Khatib:

.

******************

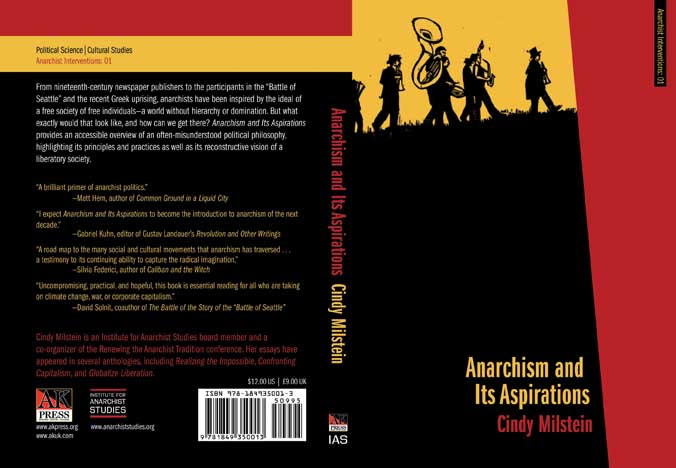

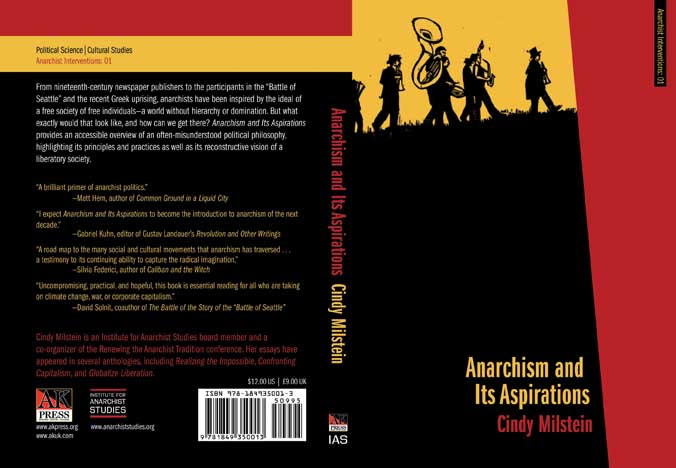

Next is the first book in the AK Press / Institute for Anarchist Studies “Anarchist Interventions Series,” Anarchism and its Aspirations, by Cindy Milstein.

From nineteenth-century newspaper publishers to the participants in the “Battle of Seattle” and the recent Greek uprising, anarchists have been inspired by the ideal of a free society of free individuals—a world without hierarchy or domination. But what exactly would that look like, and how can we get there? Anarchism and Its Aspirations provides an accessible overview of an often-misunderstood political philosophy, highlighting its principles and practices as well as its reconstructive vision of a liberatory society.

“A brilliant primer of anarchist politics.” —Matt Hern, author of Common Ground in a Liquid City

“I expect Anarchism and Its Aspirations to become the introduction to anarchism of the next decade.” —Gabriel Kuhn, editor of Gustav Landauer’s Revolution and Other Writings

“A road map to the many social and cultural movements that anarchism has traversed . . . a testimony to its continuing ability to capture the radical imagination.” —Silvia Federici, author of Caliban and the Witch

“Uncompromising, practical, and hopeful, this book is essential reading for all who are taking on climate change, war, or corporate capitalism.” —David Solnit, coauthor of The Battle of the Story of the “Battle of Seattle”

Cover design by Josh MacPhee:

.

*******************

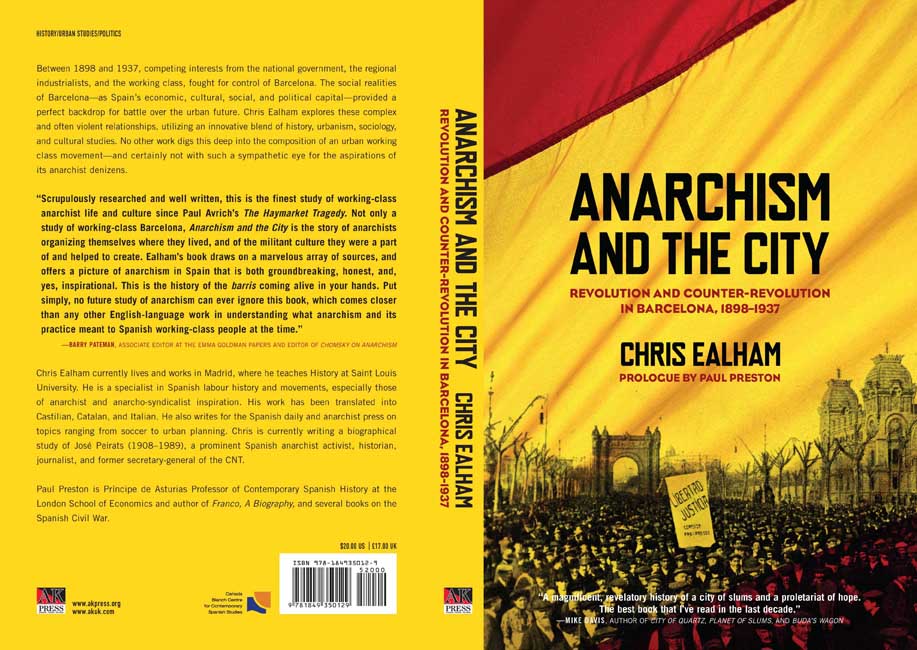

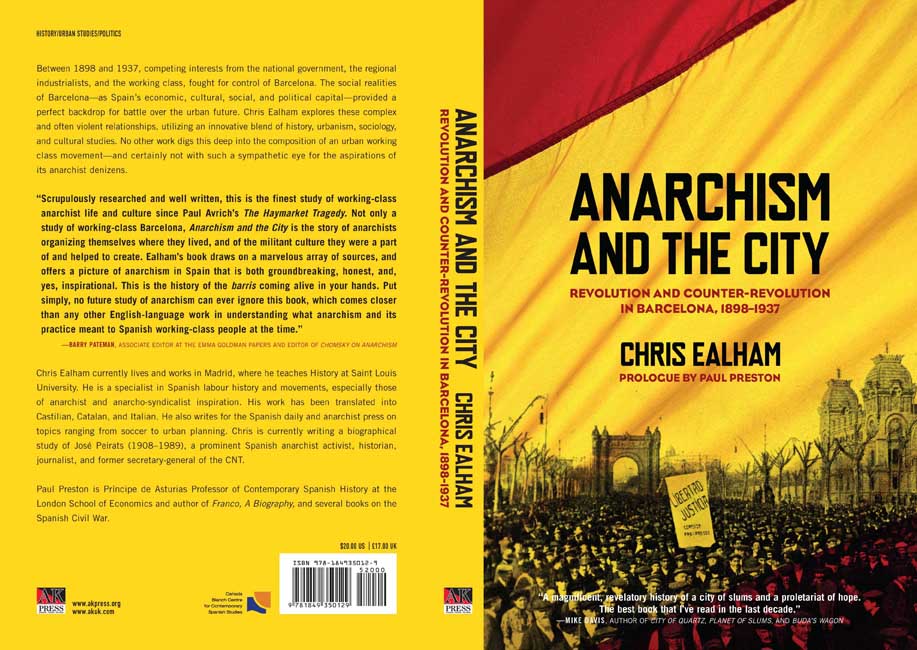

And finally, formerly available as a $200 hardcover (under the name Class, Culture and Conflict in Barcelona)—but worth every penny—is our reasonably priced Anarchism and the City by Chris Ealham. This one is published by AK Press in conjunction with The Cañada Blanch Center for Contemporary Spanish Studies and includes a prologue by Paul Preston. Here’s what we’re saying:

“A magnificent, revelatory history of a city of slums and a proletariat of hope. The best book that I’ve read in the last decade.”―Mike Davis, author of City of Quartz, Planet of Slums, and Buda’s Wagon

Between 1898 and 1937, competing interests from the national government, the regional industrialists, and the working class, fought for control of Barcelona. The social realities of Barcelona―as Spain’s economic, cultural, social, and political capital―provided a perfect backdrop for battle over the urban future. Chris Ealham explores these complex and often violent relationships, utilizing an innovative blend of history, urbanism, sociology, and cultural studies. No other work digs this deep into the composition of an urban working class movement―and certainly not with such a sympathetic eye for the aspirations of its anarchist denizens.

“Scrupulously researched and well written, this is the finest study of working-class anarchist life and culture since Paul Avrich’s The Haymarket Tragedy. Not only a study of working-class Barcelona, Anarchism and the City is the story of anarchists organizing themselves where they lived, and of the militant culture they were a part of and helped to create. Ealham’s book draws on a marvelous array of sources, and offers a picture of anarchism in Spain that is both groundbreaking, honest, and, yes, inspirational. This is the history of the barris coming alive in your hands. Put simply, no future study of anarchism can ever ignore this book, which comes closer than any other English-language work in understanding what anarchism and its practice meant to Spanish working-class people at the time.”―Barry Pateman, Associate Editor at the Emma Goldman Papers and editor of Chomsky on Anarchism

Cover design by John Yates:

Posted on February 10th, 2010 in AK Allies, AK Authors!, AK Distribution

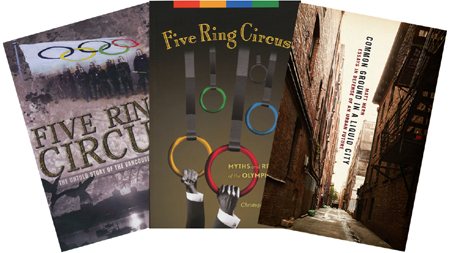

First of all, you know the drill…another month, another awesome package deal from AK. This month, in honor of the resistance to the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver, we have put together a special one for you. This “snack pack” is basically a buy-two-get-one-free deal (you get about $60 worth of stuff for $39.95, and the low shipping cost of a single item—what a bargain!). But besides being an unsurpassed value, it’s also a wealth of really important and timely information!

|

|

This month, all eyes will be on Vancouver as that most sinister corporate circus—the 2010 Winter Olympics—descends on the city. What’s wrong with the Olympics, you ask? Well, start with a history of colonialism and the fact that British Columbia remains largely unceded and non-surrendered Indigenous territory. Add the destruction of the environment, massive security operations and invasion of civil liberties, homelessness and criminalization of poverty, huge corporations raking in profits at the expense of the public, union-busting…the list goes on. But say you can’t make it up to join the protests, what will you do instead of being glued to the TV? AK Press has the solution! This month’s special package deal, or “Snack Pack,” is both timely AND cheap! Our ever-so-daintily-named “Eat Shit, Olympics!” Snack Pack includes the following three items (for the price of two, and the low shipping cost of a single book):

Titles included in the package (you can also order them individually, of course) are:

Five Ring Circus: Myths and Realities of the Olympic Games, by Christopher Shaw

This book details the history of how Vancouver won the bid for the 2010 Games, who was involved, and what the real motives were. It also describes the role of corporate media in promoting the Games, the machinations of government and business, and the opposition that has emerged.

Five Ring Circus: The Untold Story of the Vancouver 2010 Games (DVD), directed by Conrad Schmidt

A documentary film that exposes a side of the Vancouver Olympics that has not been revealed before. Find out what mayors, activists, and residents think of the 2010 Olympic games, and see how commitments to environmental, social and economic sustainability have not been honored.

Common Ground in a Liquid City: Essays in Defense of an Urban Future, by Matt Hern

This new book (published by AK Press!) examines city living, and possibilities for an urban future—looking at cities worldwide but using the author’s home city of Vancouver as a foil. Explore what it is that makes Vancouver and other cities truly livable and sustainable (hint: the answer is NOT an international mega-corporate invasion of your city).

Our comrades from the Friendly Fire Collective are going up to Vancouver and will be writing about the Olympic resistance activities going on there. You can check out their website for daily updates.

Now we’ll leave you with a very special video to get you into the true Olympic spirit:

Posted on February 9th, 2010 in AK Authors!

As most of you know, the fight to halt mountaintop removal in Appalachia is an ongoing campaign. Just two weeks ago, Climate Ground Zero rallied forces together for a tree-sit on Coal River Mountain in southern West Virginia, and independent journalist (and forthcoming AK Press author) Tricia Shapiro was there to help document the action, and spread the word. We asked Tricia, whose book on MTR resistance in Appalachia will be published by AK Press this fall, to write a report on the action for Revolution by the Book. Please feel free to repost & republish, but please contact publicity@akpress.org to let us know. We’ll be asking Tricia for regular updates on the situation in West Virginia over the coming months; if your journal or newspaper is interested in on-the-ground coverage of the CGZ actions, and other MTR-resistance fights in Appalachia, please contact us. You can also find a wealth of information on the Climate Ground Zero website.

——

Before dawn on Thursday, Jan. 21, a dozen heavily laden activists headed for the edge of a strip mine site on Coal River Mountain, in southern West Virginia. The hikers approached three trees, oak and poplar, previously selected by scouts as suitable in several ways: The trees were not far apart, about 50 or 60 feet between them. Each tree was suitable for installing a person on a platform high enough up to make removal difficult. They were in undeveloped terrain where it would be hard for mine workers to bring in heavy equipment. And they were close enough to mining activities to prevent blasting if the trees were occupied.

Working quickly, the three prospective tree sitters and their supporters hoisted plywood platforms, tarps, food, water, radios, batteries, and other essentials up into the trees. Finally, the sitters—Eric Blevins, Amber Nitchman, David Aaron Smith (also known as Planet)—settled on their platforms and pulled up their ropes.

Setting up traverse lines—ropes that would enable the sitters to move themselves and their supplies from one tree to another—was about the only thing that did not go as intended. Too many branches were in the way for lines to be set between the trees, especially in the dark, so they would have to do without. The sitters had planned to share certain supplies: They had only two cellphones and one battery-to-phone charger between them, for example. If one sitter came down early, he or she wouldn’t be able to pass unused supplies to the others. Still, each of the sitters had at least a communications radio, spare batteries, and enough food and water for a week or more. Eric, who had the cellphone charger, would be the primary contact with the outside world. Amber would minimize use of her cellphone, and the three of them would communicate as needed by radio. They would make do.

Two supporters remained on the ground by the trees. Several others would hide in the woods, too far away to see the sitters but close enough for radio contact: If the sitters said they were in danger, these off-site supporters would run to their aid. Others who helped set up the sit left and began a long hike back toward base camp, several miles away, at the headquarters for Climate Ground Zero (CGZ).

(Slideshow from the Climate Ground Zero website. Many, many more images, press releases, etc. there …)

CGZ supports the use of nonviolent civil disobedience by activists seeking to end mountaintop removal (MTR) coal mining and similar sorts of large-scale strip mining in Appalachia. In 2009, anti-MTR activists affiliated with the CGZ and Mountain Justice campaigns launched 18 civil-disobedience actions in West Virginia’s coalfields, incurring more than 130 arrests. Some of those actions, like this tree sit, were on mine sites; others took place at the front gates of mine facilities or in the offices of government officials. Most took place in or near the Coal River valley, and many focused on Coal River Mountain.

Coal River Mountain is the last intact mountain bordering the valley, with thousands of acres of continuous forest and healthy streams. It has excellent potential for a large-scale wind farm that would produce more jobs and higher local earnings and tax revenues than would strip-mining the site. In addition, a wind farm would leave nearly all of the mountain’s forest intact, allowing local people to continue to hunt and forage there, as they have done for generations. All those benefits could be sustained as long as the wind blows. MTR operations would end on the mountain in 15 years or so, leaving a flattened, treeless landscape with much-reduced wind potential and insufficient stability for installing large turbines.

Massey Energy, whose subsidiaries run most of the strip mines near Coal River valley, has long planned to strip-mine some 6,600 acres of this mountain, divided into four contiguous permit areas with a total of 18 proposed “valley fills,” where miners would dump rubble from mining nearby. Massey has not yet obtained permits for any of those valley fills. Instead, Massey’s subsidiary Marfork has permission to dump rubble from the Bee Tree permit area around the edge of the adjacent Brushy Fork sludge pond.

(more…)

Posted on February 8th, 2010 in AK Allies, Anarchist Publishers, Spanish

Novedad editorial

Durruti “el héroe del Pueblo”. 1896-1936

Autor: El Seta

“En forma de collage se recogen citas, textos, canciones, fotos, carteles…en torno a la figura del anarquista leonés, dotando a la obra de una gran frescura y dinamismo sin perder por ello en rigor histórico”.

“En forma de collage se recogen citas, textos, canciones, fotos, carteles…en torno a la figura del anarquista leonés, dotando a la obra de una gran frescura y dinamismo sin perder por ello en rigor histórico”.

21 x 30 cms., 103 páginas, color

Fundación Anselmo Lorenzo, 2010ISBN: 978-84-86864-77-4

Presentación:

Durruti “el héroe del pueblo” pretende ser un folletín ilustrado del pensamiento político, tomando su vida como hilo conductor, del anarquista español más universal, Buenaventura Durruti, siguiendo la estructura y gran parte de los textos de la biografía novelada “El corto verano de la anarquía. Vida y muerte de Durruti” de Hans Magnus Enzensberger, así como los textos del libro de Abel Paz “Durruti en la Revolución española“.

Todos los textos que van numerados son citas literales de las palabras pronunciadas por los protagonistas, ajustados a la imagen correspondiente en la mayoría de los casos o pronunciadas por los mismos en circunstancias parecidas. Se encuentran relacionadas, indicando su procedencia, al final de la historia, así como una sucinta reseña de los protagonistas de las mismas.

Al final se recogen diversos documentos en varios anexos.

La vida de Buenaventura, la vida del rebelde, del sindicalista, del revolucionario, del hombre de acción, es paradigma y espejo al mismo tiempo de la de numerosos anarcosindicalistas españoles del primer tercio del siglo XX y sigue siendo en los albores del nuevo milenio una antorcha que ilumina a todos los que luchan por un mundo más justo y más humano. Utopía, ¿quizás?.

Salud y Anarquía.

El Seta, León 2010.

Posted on February 5th, 2010 in AK Distribution

Hello AK Bloggers! How you livin’ out there? Hope everyone is doing well. Below are some books to help you make it through this month without going mad, killing your neighbor, giving away your cat, or smashing into a cop car. To all my fellow Aquariuses out there, Happy Birthdays!

1. The Screwball Asses — It took me about two hours to receive this into our AK stock just because I couldn’t stop reading it. Alongside Violence of Financial Capitalism and The German Issue Semiotext(e) has re-upped AK with some juicy goodies.

1. The Screwball Asses — It took me about two hours to receive this into our AK stock just because I couldn’t stop reading it. Alongside Violence of Financial Capitalism and The German Issue Semiotext(e) has re-upped AK with some juicy goodies.

2. Original Pluming: Trans Male Quarterly ! — This deserves an exclamation point and all you need to do is order it to find out why. From the transformative and trailblazing minds of Amos Mac and Hip Hop artist Katastrophe’s comes the first trans male magazine. Inside are helpful tips, supportive narratives, sexy photos ops, and great resources. The first issue is sold out so you better get your hands on the second very quickly.

2. Original Pluming: Trans Male Quarterly ! — This deserves an exclamation point and all you need to do is order it to find out why. From the transformative and trailblazing minds of Amos Mac and Hip Hop artist Katastrophe’s comes the first trans male magazine. Inside are helpful tips, supportive narratives, sexy photos ops, and great resources. The first issue is sold out so you better get your hands on the second very quickly.

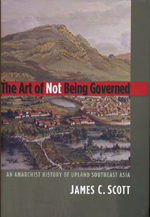

3. The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia — This book redefines our views on Asian politics, history, demographics, and even our fundamental ideas about what constitutes civilization, and challenges us with a radically different approach to history that presents events from the perspective of stateless peoples and redefines state-making as a form of “internal colonialism.” Check it out!

3. The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia — This book redefines our views on Asian politics, history, demographics, and even our fundamental ideas about what constitutes civilization, and challenges us with a radically different approach to history that presents events from the perspective of stateless peoples and redefines state-making as a form of “internal colonialism.” Check it out!

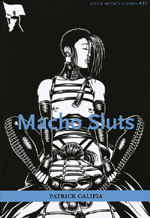

4. Macho Sluts — You could buy this book just for the cover and you would get your money’s worth. Fortunately, the collection of stories centered around San Francisco’s dyke bathhouses, sex parties, and S/M gay bars will assure you a good night’s rest as well. Best bedtime stories ever! The 1st edition survived a brutal bashing on behalf of the mainstream lesbian press in 1988. You better get the 2nd edition before Pat Robertson hears of this!

4. Macho Sluts — You could buy this book just for the cover and you would get your money’s worth. Fortunately, the collection of stories centered around San Francisco’s dyke bathhouses, sex parties, and S/M gay bars will assure you a good night’s rest as well. Best bedtime stories ever! The 1st edition survived a brutal bashing on behalf of the mainstream lesbian press in 1988. You better get the 2nd edition before Pat Robertson hears of this!

5. Please Feed Me: A Punk Vegan Cookbook — I’m not vegan but exotic spiced fruit salad + violent phobia pizza + photos of early, late, and middle-aged punk bands = very full and satisfied macio. Wait, how the hell do you make shepherds pie vegan…

5. Please Feed Me: A Punk Vegan Cookbook — I’m not vegan but exotic spiced fruit salad + violent phobia pizza + photos of early, late, and middle-aged punk bands = very full and satisfied macio. Wait, how the hell do you make shepherds pie vegan…

6. Heather Has Two Mommies — Check it, I’m not looking to have any kids in the near future. My collective budget couldn’t sustain a child. However, I am in support of peddling some literature that will help counter all the heteronormative ideas of family. This beautifully illustrated children’s book will aid a liberated education of a child whose mind is bombarded with homophobic trash on a daily basis…and the moms are hot.

6. Heather Has Two Mommies — Check it, I’m not looking to have any kids in the near future. My collective budget couldn’t sustain a child. However, I am in support of peddling some literature that will help counter all the heteronormative ideas of family. This beautifully illustrated children’s book will aid a liberated education of a child whose mind is bombarded with homophobic trash on a daily basis…and the moms are hot.

7. To Die For The People — This new release of a classic collection of Huey P. Newton’s writings and speeches traces the development of Newton’s personal and political thinking, as well as the radical changes that took place in the formative years of the Black Panther Party. Includes a new forward by Elaine Brown and edited by Toni Morrison!

7. To Die For The People — This new release of a classic collection of Huey P. Newton’s writings and speeches traces the development of Newton’s personal and political thinking, as well as the radical changes that took place in the formative years of the Black Panther Party. Includes a new forward by Elaine Brown and edited by Toni Morrison!

8. How To Make Soap: Without Burning Your Face Off — This is a new pamphlet from Raleigh Briggs the author of Make Your Place. Here, she teaches us how to create silky handmade soaps at home with basic directions, recipes, a list of resources, and assorted tips.

8. How To Make Soap: Without Burning Your Face Off — This is a new pamphlet from Raleigh Briggs the author of Make Your Place. Here, she teaches us how to create silky handmade soaps at home with basic directions, recipes, a list of resources, and assorted tips.

——-

My last two top ten are not technically “new” but we just received some fresh stock from Kersplebedeb and the information is as relevant and useful as their debuts:

9. Jailbreak Our of History: The Re-Biography of Harriet Tubman — Ninety pages of crucial revisionist history, firmly re-rooting Harriet Tubman in the context of patriarchy, race, class, and armed struggle.

9. Jailbreak Our of History: The Re-Biography of Harriet Tubman — Ninety pages of crucial revisionist history, firmly re-rooting Harriet Tubman in the context of patriarchy, race, class, and armed struggle.

10. Take Back Your Life: A Wimmin’s Guide To Alternative Health Care — Originally published by the Profane Existence anarcho-punk collective, this is an excellent practical DIY Guide—from healing common infections of the vagina and bladder to menstruation, birth control, and an understanding of AIDS.

10. Take Back Your Life: A Wimmin’s Guide To Alternative Health Care — Originally published by the Profane Existence anarcho-punk collective, this is an excellent practical DIY Guide—from healing common infections of the vagina and bladder to menstruation, birth control, and an understanding of AIDS.

Posted on February 4th, 2010 in AK Authors!, Happenings

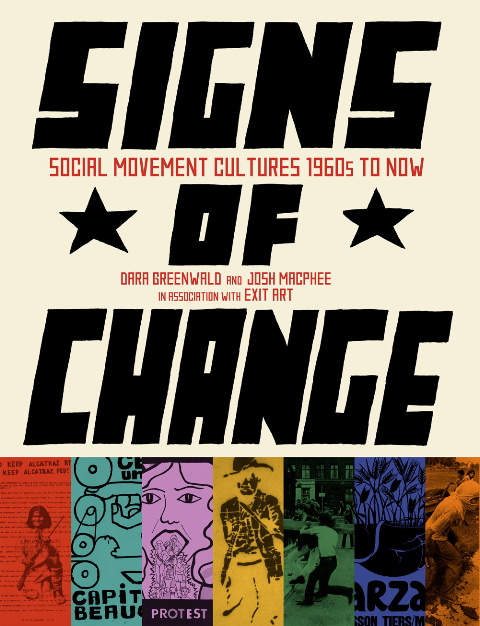

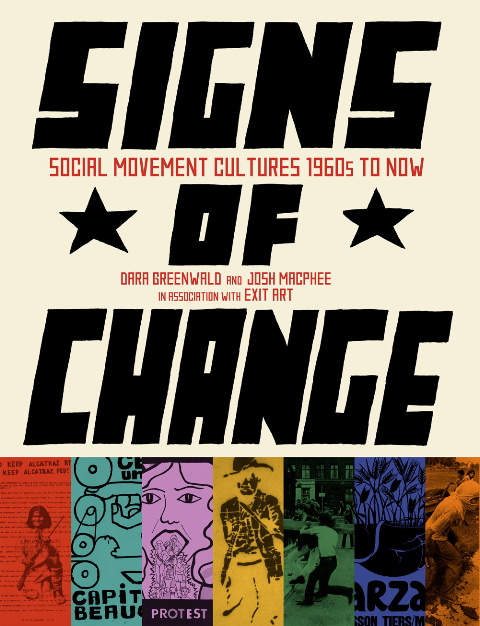

For all of you in the Portland area over the next six weeks, make sure to stop by and see Josh MacPhee and Dara Greenwald’s Signs of Change show. And for those lonely souls in Portland looking forward to an evening with Facebook, get out of the house and head down to the opening tonight at 6:30.

And of course if you’re not in PDX you can always look forward to Josh and Dara’s full-color book version of the show coming out later this year courtesy of AK Press and Exit Art.

Feldman Gallery + Project Space Hosts West Coast Premiere of Signs of Change: Social Movement Cultures 1960s to Now

Exhibition | Signs of Change: Social Movement Cultures 1960s to Now

February 4 – March 19, 2010

First Thursday Opening | Thursday, February 4, 6:30 p.m.

PNCA Main Campus Building, Feldman Gallery + Project Space, 1241 N.W. Johnson St.

PNCA hosts the West Coast premiere of Signs of Change: Social Movement Cultures 1960s to Now, featuring hundreds of posters, photographs, moving images, audio clips, and ephemera that bring to life over 40 years of activism, political protest, and campaigns for social justice. Curated by Dara Greenwald and Josh MacPhee as part of Exit Art’s Curatorial Incubator, this important and timely exhibition surveys the creative work of dozens of international social movements.

Organized thematically, the exhibition presents the creative outpourings of social movements, such as those for Civil Rights and Black Power in the United States; democracy in China; anti-apartheid in Africa; squatting in Europe; environmental activism and women’s rights internationally; and the global AIDS crisis, as well as uprisings and protests, such as those for indigenous control of lands; against airport construction in Japan; and student and worker revolution in France. The exhibition also explores the development of powerful counter-cultures that evolve beyond traditional politics and create distinct aesthetics, life-styles, and social organization.

Although histories of political groups and counter-cultures have been written, and political and activist shows have been held, this exhibition is a groundbreaking attempt to chronicle the artistic and cultural production of these movements. Signs of Change offers a chance to see relatively unknown or rarely seen works, and is intended to not only provide a historical framework for contemporary activism, but also to serve as an inspiration for the present and the future.

Signs of Change: Social Movement Cultures 1960s to Now is an exhibition produced by Exit Art, NY, and was the inaugural project of its Curatorial Incubator Program. The program expands Exit Art’s commitment to young and emerging curators and scholars in contemporary art, by giving material, financial, and human resources to developing curatorial talent. Working with Exit Art directors and staff, fellows curate large-scale exhibition projects, learn fundraising, develop outreach and educational programs, and co-publish a catalogue. Signs of Change was presented at Exit Art in 2008 and traveled to the Miller Gallery at Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA, and the Arts Center of the Capital Region (co-presented with the Department of the Arts at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Troy, NY).

In conjunction with Signs of Change, PNCA presents a selection of video screenings, focusing on women’s activist movements. Screenings are co-presented and hosted by In Other Words Women’s Books and Resources, 8 N.E. Killingsworth St., Portland, Oregon.

Signs of Change Video Screenings

Tuesday, February 16, 7 p.m.

Stronger Than Before

This film documents the militant actions and creative activities of the Women’s Encampment for a Future of Peace and Justice in Seneca, New York in 1983. Although the Boston Women’s Video Collective was formed specifically to document this encampment, they continued producing video projects after it closed. (1983, 27:00 minutes, the Boston Women’s Video Collective, courtesy of the Boston Women’s Video Collective)

Uku Hamba ‘Ze/To Walk Naked

After an exhausting fight to procure housing, a group of women in Soweto, South Africa built a settlement of makeshift shacks. When police tried to evict them with bulldozers and dogs, the women defiantly stripped naked in a peaceful protest against the destruction of their homes. This unconventional action gained massive media attention and caught the attention of filmmakers who documented the struggle in “Uku Hamba ‘Ze / To Walk Naked.” (1995, 12:00 minutes, Jaqueline Maingard, Sheila Meintjes and Heather Thompson, courtesy of Third World Newsreel)

Tuesday, February 23, 7 p.m.

Carry Greenham Home

“Carry Greenham Home” is an on-the-ground look at the activities of the Greenham Common Women’s Encampment. The film focuses not just on the women’s anti-nuclear and anti-military actions, but also on the feminist practices on which their lives were based. (1984, 66:00 minutes, Beeban Kidron and Amanda Richardson, courtesy of Women Make Movies)

Posted on February 3rd, 2010 in AK Allies, AK Distribution, Anarchist Publishers, Happenings

For your reading pleasure: a joint reportback from the two AK collective members who went down to the Los Angeles Anarchist Bookfair last weekend.

—–

Macio: Last Sunday, January 24th, AK Press attended the 2nd Annual Los Angeles Anarchist Bookfair. Suzanne and I were the collective members tasked with hauling the books and ourselves down to L.A. for the weekend.

Suzanne: I was happy to be able to attend again, as I’d had the pleasure of going down to the first L.A. Anarchist Bookfair last year and been super impressed with the way the organizers had pulled things together. I was actually so excited to go that I volunteered to split the driving duties with Macio (and I hate driving).

Macio: The bookfair was held at Barnsdall Art Park in North Hollywood. Other vendors and comrades who were present included Critical Resistance (L.A), Earth First! Journal, South Central Farmers, Modesto Anarcho, Skylight Books, L.A. Anarchist Black Cross Federation, and lots more.

Suzanne: This space was amazing—much more spacious than last year’s bookfair—and it was pretty packed the whole time. Besides the folks Macio mentioned, I was also glad to see folks from Semiotext(e), Taala Hooghan Infoshop in Flagstaff, and Revolutionary Autonomous Communities (RAC)—plus there was a good crowd of folks down from the Bay Area including the Friendly Fire Collective (our tabling neighbors and also sort of my actual neighbors!), UA in the Bay, PM Press, and lots of other familiar faces.

Macio: The event was opened up by traditional Aztec dancers and drummers. What followed was an exciting day of selling books. The AK table was packed pretty consistently with curious minds. Luckily the water fountain was located nearby so Suzanne could take frequent sips for hydration. I, on the other hand, found my calm on the balcony where the children’s day care area was set up. From what we could tell the organizers of the bookfair did a great job of scheduling engaging workshops and author panels. AK was not able to attend any of the activities but the schedule listed workshops on Indigenous Resistance, Anarchist Urban Planning Theory, Student Occupations, Bike Kitchen Mobile, and Political Prisoners, to name a few. There were also short films showing throughout the day. Although we weren’t able to check out any workshops, we definitely took advantage of all the wonderful food being offered. In addition to Food Not Bombs there were a few other independent vendors providing food and drink for a small price. One particular vendor served delicious vegan tacos and nachos with a homemade “cheese” sauce. So Good! And I scored some great t-shirts from Mass Media Distro.

Macio: The event was opened up by traditional Aztec dancers and drummers. What followed was an exciting day of selling books. The AK table was packed pretty consistently with curious minds. Luckily the water fountain was located nearby so Suzanne could take frequent sips for hydration. I, on the other hand, found my calm on the balcony where the children’s day care area was set up. From what we could tell the organizers of the bookfair did a great job of scheduling engaging workshops and author panels. AK was not able to attend any of the activities but the schedule listed workshops on Indigenous Resistance, Anarchist Urban Planning Theory, Student Occupations, Bike Kitchen Mobile, and Political Prisoners, to name a few. There were also short films showing throughout the day. Although we weren’t able to check out any workshops, we definitely took advantage of all the wonderful food being offered. In addition to Food Not Bombs there were a few other independent vendors providing food and drink for a small price. One particular vendor served delicious vegan tacos and nachos with a homemade “cheese” sauce. So Good! And I scored some great t-shirts from Mass Media Distro.

Suzanne: The great thing about working at events like this is getting to talk to so many folks who come up to our table looking for particular books (odds are, we’ve got em!), or looking for recommendations, or just being generally curious about anarchism or some aspect of radical politics or AK Press itself. The one unfortunate thing is that this all keeps us so busy that, unless we can figure out how to clone ourselves (we haven’t yet), we will always have a hard time getting away from the tables long enough to check out the other stuff that’s going on. But it did look like there was some really great talks and panels lined up. (Oh, and Macio is right, the food was delicious.) The other highlight was that Macio’s mom came and hung out at the table with us.

Macio: The bookfair started at 11am and went on until 8 or so. We were pretty much selling through our stock the whole time. We sold several copies of our latest book, Come Hell or High Water, as well as lots of classics… All in all, AK had a great time attending the L.A Anarchist Bookfair. We thank the organizers for the invite, and look forward to the next one!

Suzanne: Before we wrap this up, there’s one serious thing that we need to mention, which is that on his way home from speaking at the bookfair, Ojore Lutalo (anarchist and longtime Black Liberation political prisoner, just released in August) was arrested on an Amtrak train in Colorado and charged with “endangering public transportation,” supposedly because of a political conversation he was having on a personal phone call. He is now out on bail but in need of support (and donations). Read more about his arrest here (and click links at the end of the article for more recent updates).

|

|

| Suzanne setting up the AK table |

A thing of beauty! |

Posted on February 2nd, 2010 in AK Allies

Learning from the Movement for a New Society:

An Interview with George Lakey

In 1971 a group of Philadelphia-based activists formed the Movement for a New Society, a network of collectives dedicated to radical pacifist, feminist, and libertarian socialist politics. Over the next 18 years the organization grew to a peak of approximately 300 members in more than a dozen U.S. cities and made important contributions to anti-nuclear, radical ecology, and gender and sexual liberation struggles. The Movement for a New Society (MNS) sought to combine organizing campaigns that utilized direct action tactics with a commitment by its members to “live the revolution now” by transforming themselves and their social relationships, as well as by living collectively and establishing alternative institutions such as food co-ops. Many movement norms and forms of activism that contemporary anti-authoritarians often take for granted—the consensus process, the use of spokescouncils, internal anti-oppression work, and a focus on prefiguring in daily life the world one hopes to win—were either pioneered or heavily promoted by MNS. In 1988 the group dissolved due to the inhospitable political climate and to conflicts and challenges that arose out of MNS’ own innovative group process and strategy. (Read an historical account of Movement for a New Society here.)

Though its experiences are directly relevant to challenges facing radical organizers today, MNS remains relatively unknown. In the summer of 2008 Andy Cornell and Andrew Willis-Garcés interviewed founding member George Lakey as part of an effort to begin evaluating the MNS experience and drawing out lessons for contemporary social justice struggles.

Though its experiences are directly relevant to challenges facing radical organizers today, MNS remains relatively unknown. In the summer of 2008 Andy Cornell and Andrew Willis-Garcés interviewed founding member George Lakey as part of an effort to begin evaluating the MNS experience and drawing out lessons for contemporary social justice struggles.

——

Movement for a New Society advocated nonviolent revolution. What makes someone a nonviolent revolutionary versus a pacifist?

GL: Pacifism is hugely influenced by conflict aversion. It really shows its middle class-ness in that way, I think. There is a tremendous level of a yearning for harmony because many pacifists see conflict itself as the problem. On the other hand, nonviolent revolutionaries welcome conflict, depend on it, and see polarization as absolutely essential. Whereas most pacifists hate polarization, we welcome it as long as polarization happens in such a way that we’re on the winning side! [Laughs] And then, of course, lots of pacifists are okay with capitalism and nonviolent revolutionaries are not. They are strongly anti-capitalist and often anti-state.

Why would someone who believes in non-violence naturally oppose capitalism and the state? What’s the linkage?

GL: I think Gandhi said it best: “Inequality is a form of violence, and requires violence to defend it.” On the political front that implicates certain types of states and that certainly is the nature of capitalism—to create inequalities.

MNS placed a lot of emphasis on “process”—on the way in which the group made decisions and carried out its work. One of the abiding influences of MNS on contemporary anti-authoritarian movements is the importance placed on consensus decision-making processes. How did process become central to everything MNS did?

GL: Well, there were a number of influences. Some of us had been involved in Mississippi Freedom Summer in 1964. So we thought, “Of course, participatory democracy!” Yet, even though we yearned for community and experienced it in fleeting moments during the 60s, a lot of our nature was very individualistic. So we named it. We said, “Look, we have not been brought up to be communitarians, truly collective beings.” We realized that the price of survival with all the ego-maniacs [in the group] was going to be an explicit process. Also, some of us were influenced by A.J. Muste, who had had a really bruising experience with [authoritarian decision-making structures] even before the 1960s, especially during his time in the Trotskyist movement. So we also had some lore from elders to help us realize we were going to need a big process renovation to be able to cohere at all.

Now, how do we make decisions? From the get go, as we created a community of people interested in exploring the idea of living together and practicing the revolution, I don’t even remember it being explicitly discussed. I remember it being a shared understanding, and that was probably the Quaker influence. There were a whole bunch of Quakers involved and it was just assumed that whatever we’d end up with we would have arrived at by consensus. (The thing that is tricky about that is that we were in formation, which means anybody that could see the direction that we were going and didn’t like it could just not come to the next meeting. So that’s like attrition rather than consensus!) But then, I think we formally decided that would be our process of decision making in our first National Network Meeting which was in Madison, Wisconsin. And the Madison people who invited us there were the Center for Conflict Resolution, whose specialty was consensus. They were saying, “Consensus is the way to go, the feminist way to go.” Another formative influence in the ‘70s was the federation of intentional communities. They were heavy into consensus and many people flowed through them and were influenced by them. So that was another standard setter maybe. There was a sense that, if you were really radical, really willing to leave the capitalist cutthroat world, then consensus was part of the package—that’s what community really means.

Many contemporary activists now believe consensus and affinity groups to be crucial forms of organization, but they don’t believe in nonviolence. Did you see those things—consensus and nonviolence—as integrally linked?

GL: Well consensus is a structural attempt to get equality to happen in decision making, so it’s very much about equality. So again, back to Gandhi: where we are pushing equality, we are pushing nonviolence. Where we are allowing or encouraging inequality, there is a violent back-up there somewhere, even though it might be masked. Affinity groups speak to the question of hierarchy. The more affinity group proliferation (plus other stuff being true), the less we need hierarchical, top-down, control of social movements, the more nonviolent those movements are likely to be, I believe. That is, I think hierarchy promotes violence internally in order to maintain itself. Like, sooner or later Hugo Chavez will probably live out the nightmare that the Beltway is trying to create for him. Despite all the populism, hierarchy has this influence, I think. And hierarchs end up using violence as a way to try to keep themselves in power.

Today, a lot of activists of our generation see consensus as the only legitimate way to make decisions, no matter what task or what kind of activity they are working on. Likewise, decentralized affinity groups and spokes councils are often viewed as the only valid way of organizing for revolutionary change. What do you think the lesson of MNS should be about the uses and the shortcomings of those forms?

GL: I think that one of the reasons that MNS isn’t still around is the downside of consensus. I was never a fanatical consensus person because I thought there was a big difference between my Quaker practice and political practice. I thought there were times where consensus would be just right and other times when it wouldn’t be. But I was charmed by Seabrook [a successful mass direct action campaign against nuclear power that took place in 1976 which was organized using affinity groups, spokescouncils, and consensus process] in the sense of, “Hey, let’s see how far we can take this.” MNS was a lab. We thought, “Let’s try it here and try it there and see how it serves and how it doesn’t.”

But eventually people started getting rigid about it. The metaphor I used to use was: we fitted out a pretty good ship, and launched it in the direction of someplace. But the rudder was fixed. So long as we were going in a direction we wanted to go in and there weren’t a lot of icebergs cropping up and so on, we could just keep doing that. However, what about when we needed to make really big changes, like the Titanic would have benefited from? We weren’t able to do it because the ability to block consensus was available to, really, anybody. I got really frightened about this when I heard some of our newer members explaining the main benefit of being a member of MNS was, “You get to block consensus!” By the late 80s a huge shift had happened in the movement to make it the way to make decisions. So I think in the 70s it was cutting-edge, and in the 80s it was settling in to the way and people had to argue for parliamentary procedure if they wanted to do it.

How do you think that shift happened, so that in some sectors of the left consensus became hegemonic and came to be what made you a radical or not a radical?

GL: My first thought would be a combination of the women’s movement and the anti-nuke movement. The anti-nukes movement proved its viability amongst people who weren’t ideologically on the same page. And the women’s movement brought righteousness, as with everything they did. It was the correct way to make decisions…to liberate the voices of all.

Let’s talk about the idea of “living the revolution now” or what today is often called “prefigurative politics.” How did MNS decide that was important and what were some of the benefits?

GL: Well I think there were several impulses that lead to it. One that weighed heavily with me was a sense of demoralization that came out of the ‘60s. Many felt it was all over and we’d failed. So how do you start something new in a largely demoralized bunch of activists? We needed confidence building measures. We needed to know that we could do something now, as well as project a vision and a strategy. Another impulse was making a living. We didn’t picture being a fundraising organization with that subsidizing the activists. Activists had to provide their own income. But, by living communally, the costs go way down. So some people said, “We love the idea of printing, so how about we start a collective print shop?” And that was employment for a lot of people. And a couple other people said, “The cheaper we can get quality food, the better, so let’s start a co-op.” Cheap food, that’s great, and livelihood for the people who’d be managers. So we had a chance to create something and make it work and provide some benefit to the neighborhood. So I think several agendas came together around prefigurative politics.

So one aspect of MNS was building alternative institutions. But there was also the idea of living your life differently, according to different values—including living collectively, not just working collectively. And this seems to be another legacy of MNS. Was there an assumption that by living in new ways, other people would see the value and change their own lives in accordance?

GL: This is a great question because this was the parting of the ways between those of us who stuck and many people who had MNS on their list of egalitarian communities to go around to. I don’t know how many people I talked to who said, “We’ll I’ve just been to Acorn, I’ve just been to Twin Oaks, and here I am. What do you got?” And I’d say, “Well probably not something you’d like. Because the cutting edge of our understanding of revolution is not lifestyle change. We think of it like ashrams in Gandhi’s ideas—the ashrams that he set up, which were base camps for revolution. So what do you do in the base camp for revolution? You get ready to go on the barricades. You’re getting ready to go to jail on the ashrams. And that’s what we are doing.” And so a lot of people would say, “Thank you for not wasting my time, I’m out of here.” Because they wanted lifestyle to be the leading edge of change, and we clearly were not doing that.

For us the cadre model was really important. Our role in the neighborhood safety group, our role in the food co-op, our role in anti-nukes movement was not to get people to buy our lifestyle. That’s not the point. Now if they happen to see that we’re doing effective work side by side with them and they say, “Its funny, we’re in this very discouraging period and I’m feeling it’s all over and your not feeling despair,” maybe that’s an opening. You can talk about why you don’t come to the meetings in despair. So it’s not that we are closed or closeted about it, but you have to figure out how to be accessible enough to connect with other people.

Another former member, Betsy Raasch-Gilman, claims MNS had “a positive allergy to leadership.” For many young radicals today leadership is still anathema. When MNS was founded, what was the understanding of the role of leadership and of leaders within the group? How did that change over 17 years?

GL: My recollection of the early days of MNS was not allergy to leadership, but a growing weariness of male leadership. So I think the questioning of leadership in early MNS was much more coming from a feminist place. And very often when criticism of leadership behavior happened, it would be of masculine styles. Some members wrote a wonderful article called, “Speaking in Capital Letters.” It argued that the way men in mixed groups tend to prevail, or try to prevail, is that they say everything very emphatically as if its been thought about for months, even though they’re making up in the moment! So there was a lot of criticism of leadership behaviors but it was put in a feminist context. Which implied that we need strong women leaders who will have different styles some times. And this lead to some amazing things happening. A group of women got together and requested-slash-demanded that I give them a seminar on political theory because that was an arena they felt like they needed to catch up on with male leaders of MNS. And we didn’t talk about the fact that I, a male, was giving a seminar to women on political theory. In a lot of circles that would sound terrible. But we just saw it as skill transfer or knowledge transfer. Five years later I wouldn’t have been able to do it because, in addition to being weary about George, Bill, Dick, and so on, on the grounds that we are all men, the criticism had shifted to the fact that we were providing leadership at all. Who needs leaders?

So that changed in five years? What were the roots of that change?

GL: Well, I think that’s really complicated. There were a few things. I think it was the communitarians, in part. Because there were communitarians that went off to Twin Oaks or whatever, but there were actually others who thought, “Yep, this [MNS] is a great set-up. And we don’t mind going to demonstrations now and then.” So, people were coming to MNS that weren’t that involved in strategic political work. [Their idea of] “living the revolution now” was their big draw.

Another issue was each wave of “ism” that we responded too. Feminism was the first one, then homophobia was the one we tackled, then classism and racism. Each one of those raised more personal growth issues for each of us. There are the men and the women saying, “Oh my god, I had no idea how sexist I was. Oh, but look how homophobic I am!” So the personal growth dimension constantly got refreshed and had a sense of urgency for us, living in community, by our increasing awareness. So we had tons of work to do. And that was important work, but it was different from organizing campaigns that require a different kind of leadership.

And another thing that was going on was this consensus principle, which at first was very much about a seeking. Another of our catch phrases was, “The wisdom of the whole is wiser than the wisdom of the wisest member.” We were going after the wisdom. It’s really different when a group is seeking wisdom through consensus, and when a group is making a decision, and its like, “You’ve said enough. This is the third time you’ve spoken!” “Yeah, but he happens to have done co-ops for twenty years and we’re talking about the co-op now!” “It’s the third time he’s spoken!”

It sounds like the formality of it, rather than the underlying motivation behind the process, took over.

GL: The culture just really shifted. At one point, an organizational development consultant volunteered to work with MNS because it seemed as an organization we were getting sick. She had us do an exercise where she said, “All of you who are leaders in the organization, you go over there.” So like three people, blushing, go across the room. And she smiled and said, “Ok, all of you who do covert leadership, you go over here.” And about a third of the room gets up, including me, and goes over there. So it turned out there was this group of covert older male leadership—and this is so traditionally male, too, like we’re holding the family together. So that’s what we were doing, but not even talking to each other about it. It was just so fucked up. So I got us to be a men’s group for two years and we cried a lot with each other about how we didn’t want to be covert and have to manipulate to keep an organization afloat because we can’t come out of our closets as resourceful people. I kept saying, “What if we were to look at leadership as resources. And it depends on the issue. Like, on this issue you know more and I know less, and on another issue it’s different. So we’re scanning constantly for the most resources we could bring to bear on this decision.”

So, as someone at the heart of one of the groups that is perceived as one of the most anti-leader organizations in recent history, what would you say to young activists today who see having defined leaders as undesirable or reactionary?

GL: Our experience says it doesn’t pay to be anti-leadership. It does pay to believe in shared leadership and to look at leadership as a concept of resource rather than as the likelihood of domination.

A couple of co-founders of MNS had been on Dr. King’s national staff in the civil rights movement. So they saw, up close and personal, what it’s like to rely on a charismatic figure. Even though the founders of MNS were in love with Dr. King, we also saw the tremendous vulnerability that produces in a movement and realized we need to create a leadership understanding that does not rely on charismatic leaders. But actually I think we went too far. We went reactive to the point where, “Well, if you have charisma, don’t bother to come by here!” I’m really glad that we understood that the whole question of leadership needs to be taken up. I think we went real far on leadership issues in our laboratory experiments, and we also didn’t go far enough and that’s what did us in.

Looking back, one difference between the period of the 1970s and today is that we were still close to genuinely inspirational leadership in the 70s—that is to say Dr. King, Nelson Mandela, and some of the people around them. And that stirred our blood, however critical we were of structural weaknesses that went with that. A lot of us activists yearn to be able to give our all in an exemplary way, to somehow live out our highest aspirations, and live them out in the political realm. And I think that when a figure like that comes along, it elevates the discourse and the aspiration of people. I think it’s easier for us to try to hold ourselves in a higher place. I wouldn’t have predicted I would say this in response to this question, but this is what’s coming out. It may be temperamental; it may have to do with that sector of the population like me, who respond to human beings being exemplary. Maybe other people are more inspired by books or by collectives moving in history or right now. But there is some batch of folks, like me, who toot some on the saxophone, but when we hear in a jazz club a group really getting down, we walk out of there somehow expanded. I think that those of us who were close to the 1970s saw a lot of the expanded behavior, expanded performance, in the realm of political action. That was part of the texture of our consciousness. And I don’t see that today. The quality of political leadership in the U.S. has just been so abysmal. I think on the radical side as well as on the liberal side. Abysmal is too strong a word. But what I’m trying to point out is a lack of figures who rise above, that are like that jazz club performance group that got into the zone, that make us say, “Yes, maybe I can get into the zone someday.” And I don’t run into that condition culturally and I don’t run into activists very often who seem to resonate to that, who can tell me the last time that they’ve been to that jazz club and have been lifted in that way.

You’ve been involved in anti-authoritarian social movements for five decades. Is there anything unique to you about the younger activists you’ve worked with recently or the political movements in which they are taking action?

GL: There are some really positive, inspirational developments. For one thing, all this awareness of oppression/liberation issues. In the ‘70s, just taking on feminism was a huge, huge thing. And now we’ve got so many young people who understand a bunch of “-isms” and relationships among the “-isms” at some level in their cognitive map, if not all the way through. Also in the ‘70s there were still a lot of young activists who believed that the U.S. wasn’t structurally corrupted to its core by imperialism. They could still hold on to a believe that Vietnam was in some way an aberration or maybe it was an extreme of tendencies that could be found the lower key in other ways in Latin America or whatever. But it seems to me that younger activists are far more ready today to make a sweeping analysis. And then of course the environmental picture. When we were starting in the 70s, very few people shared our view. And now, even Al Gore does! [Laughs] So there are some real plusses in the way people start out today.

George Lakey’s first arrest was for a civil rights sit-in and he has gone on to play activist roles in a number of movements. He has authored seven social change books and has sometimes made his living teaching in college. Facilitator of over one thousand workshops on five continents, he founded the movement education center Training for Change.

Andy Cornell is an organizer and a graduate student who is completing a dissertation on mid-20th Century U.S. anarchism. He has recently written about the labor movement in Left Turn magazine.

Andrew Willis-Garcés is a community organizer in Washington, D.C.

This interview is dedicated to the memory of George Willoughby, who passed away on January 5, 2010. George Lakey writes, “George Willoughby, one of my most important mentors and a co-founder of MNS, died two nights ago at 95. George worked closely with A.J. Muste, Bayard Rustin, Dave Dellinger, and a host of others who experimented with nonviolent revolutionary approaches; for example, George was chair of the Committee for Nonviolent Action and was arrested on the high seas by the U.S. for attempting to sail into the nuclear testing zone of the Pacific. He’s been an anchor for me my entire adult life and was a prime mover in starting MNS. He was cracking jokes until a couple of minutes before his heart beat its last.”

Posted on February 1st, 2010 in AK Distribution, Happenings

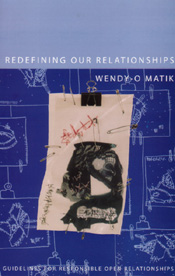

I’m willing to wager that most readers of this blog have read or at least heard tell of Wendy-O Matik’s classic guide, Redefining Our Relationships. This is a book we’ve carried a number of years, and sent out countless copies of. It’s clear that a lot of people out there are interested in building more equitable, open, free and, really, radical relationships.

I’m willing to wager that most readers of this blog have read or at least heard tell of Wendy-O Matik’s classic guide, Redefining Our Relationships. This is a book we’ve carried a number of years, and sent out countless copies of. It’s clear that a lot of people out there are interested in building more equitable, open, free and, really, radical relationships.

Luckily for all of you out there (or at least all of you in the Bay Area), Wendy will be joining us here at the AK Press warehouse this Thursday, February 4th starting at 7pm. She’ll be giving one of her radical love workshops, followed by an inclusive group discussion.

“Building on her feminist critique of love and relationships, Wendy presents the major concepts and challenges that we face trying to re-invent our relationships outside the dominant social paradigm. Radical love is the freedom to love whom you want, how you want, and as many as you want, so long as personal integrity, respect, honesty, and consent are at the core of any and all relationships. Radical love primarily focuses on love and intimacy, not sex and sexual conquest. At the heart of this work are three components: feminism, social activism, and revolution. The workshop is followed by a discussion and intended to create a non-judgmental support group.”

To read more about Wendy and her work, check out her website. Oh, and whether or not you make it out to the workshop, be sure to keep checking back right here on our blog–I have a feeling you might be hearing more from her soon.

Posted on January 31st, 2010 in Anarchist Publishers

Former AK Press collective member (and perpetual helper and copyeditor) Chuck Morse sent me a link to Süreyyya Evren’s blog post about his experiences doing anarchist publishing in Turkey. It’s an interesting recounting and analysis of the methods, strategies, and complications of one group’s attempts to disseminate anarcho-proaganda. And here it is…

Former AK Press collective member (and perpetual helper and copyeditor) Chuck Morse sent me a link to Süreyyya Evren’s blog post about his experiences doing anarchist publishing in Turkey. It’s an interesting recounting and analysis of the methods, strategies, and complications of one group’s attempts to disseminate anarcho-proaganda. And here it is…

******************

Alternative Publishing Experiences in Istanbul

Süreyyya Evren

I would like to base this “action note” on our experiences of publishing anarchist materials in Istanbul in the last decade as an affinity group that mainly works on postanarchism. I will try to focus on two aspects of our experience.

First I would like to explain our position and our approach. Briefly, we have been actively working on a research and publication project in Istanbul from a poststructuralist anarchist perspective, or we can say a postanarchist perspective. Of course, what we understand by these terms needs to be discussed in detail, but at the risk of simplifying we can say it has been a kind of updated pananarchism; an anarchism that is understood beyond the limits of politics and one which includes post-eurocentric, non-modernistic elements, contemporary theoretical developments, and culture in a broad sense, which leads to a conception of an anarchism that grabs different fields and everyday life. When we are asked to summarize what we try to do, we simply describe it as a pursuit for heterodoxies in every possible field and an effort to enhance these fields of heterodoxies and challenge orthodoxies everywhere. And we make use of the works of contemporary philosophers like Foucault or Deleuze, so-called poststructuralists, and relating this body of theory to other sorts of political writings of people like Bakhtin or Franz Fanon. We try to develop an open methodology which doesn’t hesitate to employ third world studies, art practices and art theory, and political forms of activities. So although we had good relations with postanarchists of the English-speaking world (like Todd May, Saul Newman, and Lewis Call), we have developed a different path since we first made our postanarchist publications in mid-90s.

First I would like to explain our position and our approach. Briefly, we have been actively working on a research and publication project in Istanbul from a poststructuralist anarchist perspective, or we can say a postanarchist perspective. Of course, what we understand by these terms needs to be discussed in detail, but at the risk of simplifying we can say it has been a kind of updated pananarchism; an anarchism that is understood beyond the limits of politics and one which includes post-eurocentric, non-modernistic elements, contemporary theoretical developments, and culture in a broad sense, which leads to a conception of an anarchism that grabs different fields and everyday life. When we are asked to summarize what we try to do, we simply describe it as a pursuit for heterodoxies in every possible field and an effort to enhance these fields of heterodoxies and challenge orthodoxies everywhere. And we make use of the works of contemporary philosophers like Foucault or Deleuze, so-called poststructuralists, and relating this body of theory to other sorts of political writings of people like Bakhtin or Franz Fanon. We try to develop an open methodology which doesn’t hesitate to employ third world studies, art practices and art theory, and political forms of activities. So although we had good relations with postanarchists of the English-speaking world (like Todd May, Saul Newman, and Lewis Call), we have developed a different path since we first made our postanarchist publications in mid-90s.

Secondly, I would like to give some details and show how we tried to apply different forms of media in different periods of our project. I will try to draw the advantages and disadvantages we found in various forms of publishing. I hope this will be a useful survey of diverse modes of publishing, which gives clues for various possibilities. The methods we have been using for spreading and testing our political position will be evaluated together with their results.

Especially in the last 12 years, working as an affinity group of people who are interested in similar subjects, theoretical and political stances, we have passed through different alternative publication experiences. Here I would like to summarize and categorize these and then maybe compare and discuss possibilities.

We have had three main phases of alternative publishing.

1. The first period: Karasin Anarchist Collective.

Karasin Anarchist Collective was active between 1996 and 1998. It was a totally independent publishing period relying heavily on photocopy (xerox) magazines, newspapers, texts and pamphlets. No legal procedure was involved. As for the distribution of our publications we have used already existing networks of subcultural fanzine distribution; we also built a web site publishing everything we made so far in Karasin Anarchist Collective.

2. The second period: A period of “détournement“—Working inside other publications and media.

The second period of our alternative publishing dates to the period between 2000 and 2003. We have worked inside already existing structures, such as an established humanist literature magazine, a comics and culture magazine, a radio station, and a publication house—and continued to develop our postanarchist studies, combining them with different grounds and media.

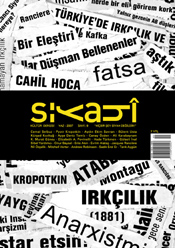

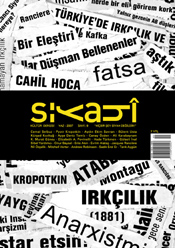

3- The third period: Independent publishing and launching a separate legal magazine of our own—Siyahi.

That period was initiated in 2003 as an autonomous web site. After that we started to publish our magazine Siyahi, devoted to focus on postanarchist thought in November 2004. In total, we have published 7 issues of Siyahi.

Experiences

The first period: Karasin Anarchist Collective

Between 1996-1998, we called ourselves the Karasin Anarchist Collective. And in the context of the Karasin project we published a photocopied (xerox) magazine, a photocopied newspaper and pamphlets. We also used photocopy for copying certain texts. In total we did 2 issues of the magazine, 3 issues of the newspaper and 11 pamphlets. Karasin Anarchist Collective (in some places we called ourselves the Karasin Working Group) was composed of a small core of a few people [footnote 1].

Karasin was formed of people who were translating, writing, reading, and discussing. I was active with a web site, photocopy magazine, photocopy newspaper, and pamphlets. But these were not its only activities. Long discussions had preceded our publications. As I remember it, a discussion period of nearly two years with different people came before publishing anything. We were having endless reflective talks about what we want to do. Before starting Karasin Anarchist Publications we did some works with the Karasin “logo” in some events in literature and politics.

Karasin was formed of people who were translating, writing, reading, and discussing. I was active with a web site, photocopy magazine, photocopy newspaper, and pamphlets. But these were not its only activities. Long discussions had preceded our publications. As I remember it, a discussion period of nearly two years with different people came before publishing anything. We were having endless reflective talks about what we want to do. Before starting Karasin Anarchist Publications we did some works with the Karasin “logo” in some events in literature and politics.

The first “photocopy action” we did was against one of the most established famous Turkish novelists. We wanted to challenge an elitist advertising campaign which abused the cultural field to create a status distance, an event followed later by a total commercialization of the publishing field. The first action can be understood as an action against market determined literature/culture.

We published the first Karasin magazine on the 14th of April 1996. This was the day the Russian poet Mayakovski died. And although he was not an anarchist, we had respect for him and his political stance and the gesture in this reference underlined our ties with literature as well [footnote 2].

Before Karasin, I personally had an experience with photocopy publishing already. With some friends, we had made photocopied books and magazines. Photocopying, in the early 1990s, was an important element of alternative publishing and alternative distribution for us. We had photocopied books and we even tried to distribute photocopied poems on the streets.

We had a completely fictive “photocopy publication house” called the “Zenci Kitaplar” (meaning “Negro Books”). Of course, there was nothing like that officially. We were photocopying literature books, stories and poems.

As the second action of Karasin Group, we duplicated an article of a very well known Turkish art critic as a form of protest. In that article the writer was talking about the necessity of the institution of police as such. As a result of our protest, which was only duplicating his article by stamping our logo on it, we triggered protests of fellow leftists directed to this critic.

After these two actions we started the pamphlets and Karasin magazine and turned our faces more to anarchism than literature.

The second issue of the KARASIN zine, 8 May 1997, was dedicated to the memory of the execution of Alexander Ulyanov who was Lenin’s brother and who attempted to assassinate the Russian czar Alexander III. For us, this dedication was also an indirect sign of our anti-Leninism.

The Karasin pamphlets we published included Sergey Neçayev’s Revolutionary Catechism, Peter Kropotkin’s Anarchism in Socialist Evolution, Anarchism, and On Order, Mikhail Bakunin’s Revolutionary Catechism, and Emma Goldman’s The Psychology of Political Violence. We also published Franz Fanon’s A Sociology of a Revolution (a chapter of “Transformation of a Family”), Fyodor Dostoyevski’s The Dream of a Strange Person, an anarchist interview with Zapatistas by Love and Rage Revolutionary Anarchist Federation in May 1994, a book on the 1992 Los Angeles uprising prepared by combining texts from different fanzines and essays about events.

(more…)

“En forma de collage se recogen citas, textos, canciones, fotos, carteles…en torno a la figura del anarquista leonés, dotando a la obra de una gran frescura y dinamismo sin perder por ello en rigor histórico”.

“En forma de collage se recogen citas, textos, canciones, fotos, carteles…en torno a la figura del anarquista leonés, dotando a la obra de una gran frescura y dinamismo sin perder por ello en rigor histórico”.

Macio: The event was opened up by traditional Aztec dancers and drummers. What followed was an exciting day of selling books. The AK table was packed pretty consistently with curious minds. Luckily the water fountain was located nearby so Suzanne could take frequent sips for hydration. I, on the other hand, found my calm on the balcony where the children’s day care area was set up. From what we could tell the organizers of the bookfair did a great job of scheduling engaging workshops and author panels. AK was not able to attend any of the activities but the schedule listed workshops on Indigenous Resistance, Anarchist Urban Planning Theory, Student Occupations, Bike Kitchen Mobile, and Political Prisoners, to name a few. There were also short films showing throughout the day. Although we weren’t able to check out any workshops, we definitely took advantage of all the wonderful food being offered. In addition to Food Not Bombs there were a few other independent vendors providing food and drink for a small price. One particular vendor served delicious vegan tacos and nachos with a homemade “cheese” sauce. So Good! And I scored some great t-shirts from

Macio: The event was opened up by traditional Aztec dancers and drummers. What followed was an exciting day of selling books. The AK table was packed pretty consistently with curious minds. Luckily the water fountain was located nearby so Suzanne could take frequent sips for hydration. I, on the other hand, found my calm on the balcony where the children’s day care area was set up. From what we could tell the organizers of the bookfair did a great job of scheduling engaging workshops and author panels. AK was not able to attend any of the activities but the schedule listed workshops on Indigenous Resistance, Anarchist Urban Planning Theory, Student Occupations, Bike Kitchen Mobile, and Political Prisoners, to name a few. There were also short films showing throughout the day. Although we weren’t able to check out any workshops, we definitely took advantage of all the wonderful food being offered. In addition to Food Not Bombs there were a few other independent vendors providing food and drink for a small price. One particular vendor served delicious vegan tacos and nachos with a homemade “cheese” sauce. So Good! And I scored some great t-shirts from

Though its experiences are directly relevant to challenges facing radical organizers today, MNS remains relatively unknown. In the summer of 2008 Andy Cornell and Andrew Willis-Garcés interviewed founding member George Lakey as part of an effort to begin evaluating the MNS experience and drawing out lessons for contemporary social justice struggles.

Though its experiences are directly relevant to challenges facing radical organizers today, MNS remains relatively unknown. In the summer of 2008 Andy Cornell and Andrew Willis-Garcés interviewed founding member George Lakey as part of an effort to begin evaluating the MNS experience and drawing out lessons for contemporary social justice struggles.

Former AK Press collective member (and perpetual helper and copyeditor) Chuck Morse sent me a link to Süreyyya Evren’s

Former AK Press collective member (and perpetual helper and copyeditor) Chuck Morse sent me a link to Süreyyya Evren’s  First I would like to explain our position and our approach. Briefly, we have been actively working on a research and publication project in Istanbul from a poststructuralist anarchist perspective, or we can say a postanarchist perspective. Of course, what we understand by these terms needs to be discussed in detail, but at the risk of simplifying we can say it has been a kind of updated pananarchism; an anarchism that is understood beyond the limits of politics and one which includes post-eurocentric, non-modernistic elements, contemporary theoretical developments, and culture in a broad sense, which leads to a conception of an anarchism that grabs different fields and everyday life. When we are asked to summarize what we try to do, we simply describe it as a pursuit for heterodoxies in every possible field and an effort to enhance these fields of heterodoxies and challenge orthodoxies everywhere. And we make use of the works of contemporary philosophers like Foucault or Deleuze, so-called poststructuralists, and relating this body of theory to other sorts of political writings of people like Bakhtin or Franz Fanon. We try to develop an open methodology which doesn’t hesitate to employ third world studies, art practices and art theory, and political forms of activities. So although we had good relations with postanarchists of the English-speaking world (like Todd May, Saul Newman, and Lewis Call), we have developed a different path since we first made our postanarchist publications in mid-90s.

First I would like to explain our position and our approach. Briefly, we have been actively working on a research and publication project in Istanbul from a poststructuralist anarchist perspective, or we can say a postanarchist perspective. Of course, what we understand by these terms needs to be discussed in detail, but at the risk of simplifying we can say it has been a kind of updated pananarchism; an anarchism that is understood beyond the limits of politics and one which includes post-eurocentric, non-modernistic elements, contemporary theoretical developments, and culture in a broad sense, which leads to a conception of an anarchism that grabs different fields and everyday life. When we are asked to summarize what we try to do, we simply describe it as a pursuit for heterodoxies in every possible field and an effort to enhance these fields of heterodoxies and challenge orthodoxies everywhere. And we make use of the works of contemporary philosophers like Foucault or Deleuze, so-called poststructuralists, and relating this body of theory to other sorts of political writings of people like Bakhtin or Franz Fanon. We try to develop an open methodology which doesn’t hesitate to employ third world studies, art practices and art theory, and political forms of activities. So although we had good relations with postanarchists of the English-speaking world (like Todd May, Saul Newman, and Lewis Call), we have developed a different path since we first made our postanarchist publications in mid-90s. Karasin was formed of people who were translating, writing, reading, and discussing. I was active with a web site, photocopy magazine, photocopy newspaper, and pamphlets. But these were not its only activities. Long discussions had preceded our publications. As I remember it, a discussion period of nearly two years with different people came before publishing anything. We were having endless reflective talks about what we want to do. Before starting Karasin Anarchist Publications we did some works with the Karasin “logo” in some events in literature and politics.