Posted on May 9th, 2014 in Events

Author Maia Ramnath will be speaking on Decolonizing Anarchism and Kristian Williams will be speaking on a panel entitled “Informants: Types, Cases & Warning Signs.”

More info and complete schedule are available at https://lawandisorder.wordpress.com/.

Posted on May 9th, 2014 in Events

Visit http://www.anarchistbookfair.net/ for more info.

Posted on April 29th, 2014 in About AK, AK Authors!, AK Book Excerpts, AK News

Remember when Lula’s election in Brazil offered some pretense of hope to certain folks on the international left? Remember how the liberals and reformists just stopped referring to him as the New Great Hope once his policies became clear? Brazil has since emerged as a powerful new player on the geopolitical stage, with Lula embracing the legacy of the country’s oligarchic past, paying off huge IMF loans years ahead of schedule, and placing Brazil at the center of political and economic power in the region.

Raul Zibechi’s The New Brazil: Regional Imperialism and the New Democracy is on it’s way back from the printer. Get your order in today, get 25% off, and get schooled not only on exactly how Brazil became the poster child for neoliberal capitalism, but also on how unrest is growing in Brazil to a point that questions the very foundations capital and the state.

Posted on April 25th, 2014 in AK Allies, AK Distribution, Anarchist Publishers

Did you know that some of the folks involved with the Institute for Anarchist Studies (anarchist grant-givers extraordinaires, and also the co-publishers of our Anarchist Interventions series!) put out a journal, too? Well, now you do—and if you’re the journal-reading type, you should really check it out. It’s been looking pretty snazzy as of late, thanks to some new cover designs and illustrations by Josh MacPhee. And it’s not just good looking! It’s got substance, too—including, in their new issue (#27), contributors’ different takes on the idea of “strategy.” You can see more about the issue, and order your copy (or back issues) HERE.

Did you know that some of the folks involved with the Institute for Anarchist Studies (anarchist grant-givers extraordinaires, and also the co-publishers of our Anarchist Interventions series!) put out a journal, too? Well, now you do—and if you’re the journal-reading type, you should really check it out. It’s been looking pretty snazzy as of late, thanks to some new cover designs and illustrations by Josh MacPhee. And it’s not just good looking! It’s got substance, too—including, in their new issue (#27), contributors’ different takes on the idea of “strategy.” You can see more about the issue, and order your copy (or back issues) HERE.

To give you just a taste of what’s included in the new issue, here’s part of an interview by Perspectives editor Lara Messersmith-Glavin:

An Excerpt from “OCTAVIA’S BROOD: SCIENCE FICTION STORIES FROM SOCIAL JUSTICE MOVEMENTS—An Interview with Walidah Imarisha.”

Co-editors adrienne maree brown and Walidah Imarisha are compiling an anthology of science and speculative fiction, fantasy, horror, and magical realist short fiction, all written by activists working for social change. Under the umbrella of what they call ‘visionary fiction,’ the editors seek to draw from the imaginative and creative potential that exists in the realm of literature to inspire and guide the strategies and dreams of the radical movement.

…

Can you talk a little about the importance of thought experiments and prefigurative dreaming in the development of political praxis? What are some examples of this?

Can you talk a little about the importance of thought experiments and prefigurative dreaming in the development of political praxis? What are some examples of this?

My co-editor adrienne has said that sci fi is the perfect “exploring ground,” that it gives organizers the opportunity to play with different outcomes and strategies before we have to deal with the real world costs. Based on that, adrienne has been doing Octavia Butler Emergent Strategy Sessions across the country, coming out of a Transformative Justice space at the Allied Media Conference a few years ago. In the Transformative Justice Science Fiction Reader a collective of folks put out, they wrote, “We are four power geeks who come to the Allied Media Conference every year, and we have been developing a space for conversation around science fiction as a tool for our organizing and futurizing… Over the past few years we found each other out, as people thinking about TJ, and as sci fi geeks seeing interesting examples of potential futures rooted in TJ approaches in our isolated reading experiences.”

Emergent strategy focuses on the idea of strategizes that arise organically. You collectively have a shared vision and values, but rather than having a five year strategic plan, you recognize that in a constantly changing landscape, your strategies must be fluid and flexible, must react to the surroundings. It also allows you to use the resources around you, to find value in things that previously you may have dismissed as trash. This idea is really encapsulated in Butler’s book Parable of the Sower, which follows the main character Olamina, who is a young Black woman who lives in a slightly more dystopic future in a gated community. She begins studying skills needed to survive outside of the walls, packs a survival kit bag, and begins envisioning other ways the world could be. When the community is attacked and the walls fall, she finds herself on the outside with her bag, her knowledge and her dreams. She finds people along the way who collectively dream with her to imagine what a new community can look like.

I wrote an article “Science Fiction and Prison Abolition: Lessons To Build Our Futures” for an upcoming issue of The Abolitionist, because I feel that sci fi is actually an ideal place to explore something like prison abolition. Many folks are completely unfamiliar with the idea of community accountability processes that do not depend on the criminal justice system and the prison industrial complex. So this is a great opportunity to have that exploring ground adrienne talked about, to say, without confining us to reality at first, what else is there?

One of our stories in Octavia’s Brood does just that – Kalamu ya Salaam’s story “Manhunter” (an excerpt from a larger piece) focuses on a community of women warriors and leaders who are attempting to keep the human race alive. One of the warriors kills another, and they have a gathering to decide what is to be done with her. It is a powerful scene that shows the complexities of community accountability, and offers solutions rooted in healing rather than retribution.

My partner David Walker, whose story “The Token Superhero” also appears in Octavia’s Brood, wrote, “Life would be easier if people understood that you can be a hero without having a villain.”

Our ability to tell stories shapes how we view our reality around us. If we only hear stories that neatly package good and evil with no understanding of the complexities of situations, how can we begin to see the world through lenses that take into account complexity?

As Black feminist thinker and poet Alexis Pauline Gumbs (also an Octavia’s Brood contributor) said when asked how abolition and science fiction connected to her, “For me prison abolition is a speculative future. It imagines a species with a set of fully developed powers that are right now only fledgling. We are that species.”

Your forthcoming collection owes a great deal of its framework to the thought and writing of Octavia Butler. Ursula LeGuin is often cited as a sci fi writer who explores issues of gender (Left Hand of Darkness) and anarchist social organization (The Dispossessed); Kim Stanley Robinson’s Mars trilogy grappled with revolution and coalition-building on a planetary scale; Marge Piercy contrasted utopian and dystopian possible futures (Woman on the Edge of Time.) Who are some of the writers that have moved you the most, politically speaking, and what kinds of issues or insights did they address the most successfully? Which issues remain untouched?

Yes, we definitely owe much to Octavia Butler. We call ourselves her brood (a nod to her collection of books Lilith’s Brood) – her children; we do not claim to be Octavia or to do what she would, but we believe we are carrying on that work in countless multitudes of ways, just as she carried on the work handed down to her.

One of our contributors Alexis Pauline Gumbs quotes from an interview Octavia Butler did in the 1980s, where she was asked how it felt to be THE Black female sci fi writer. And she said she never wanted that title. She wanted to be one of many Black female sci fi writers. She wanted to be one of thousands of folks writing themselves into their present and into the future. We believe that is the right that Octavia claimed for each of us – the right to dream as ourselves, individually and collectively. But we also think it is a responsibility she handed down – are we brave enough to imagine beyond the boundaries of “the real,” and then do the hard work of sculpting reality from our dreams?

And we also want to honor many other writers, especially those living at the intersections of multiple identities and oppressions, who have dreamed new worlds and then set about the hard work of making them reality. We know WEB DuBois wrote visionary fiction in 1920, using it as another avenue for discussing the racial landscape of this country, and we want to honor that this lineage of work is long. It is actually ancient. Specifically for adrienne and myself as two Black women, we know that our enslaved ancestors were visionary fiction creators; while in chains, they dreamed of us, their children’s children, free, which was complete science fiction at that time. And then they bent reality to create us. It’s vital for those of us from communities with historic and collective oppression to remember each of us is science fiction. And as such, this is part of that responsibility Octavia laid down for us – we have a responsibility to those who came before, and to those who come after.

To read the rest of the interview—and lots more—check out the new issue!

Posted on April 17th, 2014 in About AK

We’re counting the minutes. At some point today, a truck will arrive with newly minted copies of our Malatesta anthology: The Method of Freedom. We’re all big fans of Malatesta’s thought and writing, his tactical insights, his no-nonsense approach, and his uncommon ability to remain generous and comradely even as he debates opponents into smithereens. We like him so much that this anthology will be followed, year by painstaking year, by our ten-volume The Complete Works of Malatesta.

For now, we offer an excerpt as evidence of Malatesta’s continued relevance. It’s his take on the relationship between riots and revolutions (turns out he’s a fan of both), with a few additional paragraphs addressing the question of police infiltration, the nineteenth-century version of snitchjaketing, and how a vital movement should deal with both.

| Click here for the excerpt. |

|

Click here to learn more

about the book. |

|

Posted on April 11th, 2014 in AK Authors!, AK News, Happenings

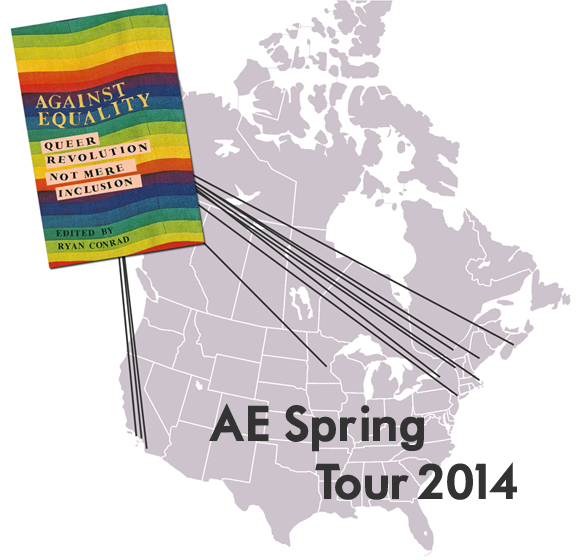

Members of the Against Equality collective have an impressive list of events lined up this spring throughout the U.S. and Canada, to celebrate the release of Against Equality: Queer Revolution, Not Mere Inclusion. If you’re lucky, you can catch an event near you. And if you’re not so lucky this time around, you can always get in touch with them and invite them to speak on their next tour!

Members of the Against Equality collective have an impressive list of events lined up this spring throughout the U.S. and Canada, to celebrate the release of Against Equality: Queer Revolution, Not Mere Inclusion. If you’re lucky, you can catch an event near you. And if you’re not so lucky this time around, you can always get in touch with them and invite them to speak on their next tour!

SPRING 2014 EVENTS:

Apr 12 @ 10:50am: Radical Archives Conference, Cantor Film Center Theater, New York University (NYC)

Apr 16 @ 4:30pm: Kagin Ballroom, Macalester College (Saint Paul, MN)

Apr 19 @ 7pm: Bureau of General Services – Queer Division (NYC)

Apr 22 @ 4:30pm: Axinn 229, Middlebury College (Middlebury, VT)

Apr 23 @ 6:30pm: Concordia Coop Bookstore (Montreal, QC)

Apr 24 @ 8pm: Queer Possibilities Lecture Series, Alteregos Cafe (Halifax, NS)

Apr 26 @ 7pm: Calamus Books (Boston, MA)

May 2 @ Time TBA: Bates College (Lewiston, ME)

May 4 @ 6pm: Artists at Work Space, Maine College of Art (Portland, ME)

May 5 @ 4pm: UC San Diego (San Diego, CA)

May 6 @ 4pm: MultiCultural Center Lounge, UC Santa Barbara (Santa Barbara, CA)

May 10 @ 7:30pm: Stories Books & Cafe (Los Angeles, CA)

Keep an eye on the Against Equality website for the most up-to-date tour news and event information.

Posted on April 5th, 2014 in AK Allies, AK Authors!

The interview below was conducted and published by the group Anarchist Affinity, in Melbourne, Australia. You can read the original (and check out their site) here.

Global Fire – South African author Michael Schmidt on the Global Impact of

Revolutionary Anarchism

Michael Schmidt is an investigative journalist, an anarchist theorist and a radical historian based in Johannesburg, South Africa. He has been an active participant in the international anarchist milieu, including the Zabalaza Anarchist Communist Front. His major works include ‘Cartography of Revolutionary Anarchism (2013, AK Press) and, with Lucien van der Walt, ‘Black Flame: The Revolutionary Class Politics of Anarchism and Syndicalism’ (2009, AK Press).

Michael Schmidt is an investigative journalist, an anarchist theorist and a radical historian based in Johannesburg, South Africa. He has been an active participant in the international anarchist milieu, including the Zabalaza Anarchist Communist Front. His major works include ‘Cartography of Revolutionary Anarchism (2013, AK Press) and, with Lucien van der Walt, ‘Black Flame: The Revolutionary Class Politics of Anarchism and Syndicalism’ (2009, AK Press).

In your recent book, Cartography of Revolutionary Anarchism (AK Press, USA, 2013), you argue that anarchists have often failed to draw insights from anarchist movements outside of Western Europe. What lessons does the global history of anarchism have to offer those engaged in struggle today?

The historical record shows that anarchism’s primary mass-organisational strategy, syndicalism, is a remarkably coherent and universalist set of theories and practices, despite the movement’s grappling with a diverse set of circumstances. From the establishment of the first non-white unions in South Africa and the first unions in China, through to the resistance to fascism in Europe and Latin America – the establishment of practical anarchist control of cities and regions, sometimes ephemeral, sometimes longer lived in countries as diverse as Macedonia (1903), Mexico (1911, 1915), Italy (1914, 1920), Portugal (1918), Brazil (1918), Argentina (1919, 1922), arguably Nicaragua (1927-1932), Ukraine (1917-1921), Manchuria (1929-1931), Paraguay (1931), and Spain (1873/4, 1909, 1917, 1932/3, and 1936-1939).

The results of the historically-revealed universalism are vitally important to any holistic understanding of anarchism/syndicalism:

Firstly, that the movement arose in the trade unions of the First International, simultaneously in Mexico, Spain, Uruguay, and Egypt from 1868-1872 (in other words, it arose internationally, on four continents, and was explicitly not the imposition of a European ideology);

Secondly, there is no such thing within the movement as “Third World,” “Global Southern” or “Non-Western” anarchism, that is in any core sense distinct from that in the “Global North”. Rather that they are all of a feather; the movement was infinitely more dominant in most of Latin America than in most of Europe. The movement today is often more similar in strength to the historical movements in Vietnam, Lebanon, India, Mozambique, Nigeria, Costa Rica, and Panama – so to look to these movements as the “centre” of the ideology produces gross distortions.

The lessons for anarchists and syndicalist from “the Rest” for “the West” can actually be summed up by saying that the movement always was and remains coherent because of its engagements with the abuse of power at all levels.

How is anarchism still relevant in the world today? What do anarchist ideas about strategy and tactics have to offer people active in social movements today?

I’d say there are several ways in which anarchism is relevant today:

1) It provides the most comprehensive intersectoral critique of not just capital and the state; but all forms of domination and exploitation relating to class, gender, race, colour, ethnicity, creed, ability, sexuality and so forth, implacably confronting grand public enemies such as war-mongering imperialism and intimate ones such as patriarchy. It is not the only ideology to do this, but is certainly the main consistently freethinking socialist approach to such matters.

2) With 15 decades of militant action behind it, it provides a toolkit of tried-and proven tactics for resistance in the direst of circumstances, and, has often risen above those circumstances to decentralise power to the people. These tactics include oppressed class self-management, direct democracy, equality, mutual aid, and a range of methods based in the conception that the means we use to resist determine the nature of our outcomes. The global anti-capitalist movement of today is heavily indebted to anarchist ethics and tactics for its internal democracy, flexibility, and its humanity.

3) Strategically, we see these tactics as rooted in direct democracy, equality, and horizontal confederalism (today called the “network of networks”), in particular in the submission of specific (self-constituted) anarchist organisations to the oversight of their communities, which then engage in collective decision-making that is consultative and responsible to those communities. It was the local District Committees, Cultural Centres, Consumer Co-operatives, Modern Schools, and Prisoner-support Groups during the Spanish Revolution that linked the great CNT union confederation and its Iberian Anarchist Federation (FAI) allies to the communities they worked within: the militia that fought on the frontlines against fascism, and the unions that produced all social wealth would have been rudderless and anchorless without this crucial social layer to give them grounding and direction. In order to have a social revolution of human scale, we submit our actions to the real live humans of the society that we work within: this is our vision of “socialism”.

In sum, anarchism’s “leaderless resistance” is about the ideas and practices that offer communities tools for achieving their freedom, and not about dominating that resistance. Anarchists ideally are fighting for a free world, not an anarchist world, one in which even conservatives will be freed of their statist, capitalist and social bondage to discover new ways of living in community with the rest of us. (more…)

Posted on April 4th, 2014 in AK Distribution, Current Events

The Winter We Danced is a brand-new collection of writing on the Idle No More movement. We at AK Press Distro have been anxiously awaiting getting this new book from our friends at Arbeiter Ring Publishing, ever since we first heard about it. And we weren’t the only ones—we’ve been fielding lots of calls and emails from other folks eager to read the words of the folks involved in this inspiring moment of Indigenous organizing. The waiting is over: the book is here in our hands, and can be in yours too! The publishers were gracious enough to give us permission to post the editors’ introduction to the book here, to give you all a better sense of the book so that you, too, can be excited about it. So here it is, we think it speaks for itself.

—

Idle No More:

Idle No More:

The Winter We Danced

The Kino-nda-niimi Collective

Indigenous peoples have been protecting homelands; maintaining and revitalizing languages, traditions, and cultures; and attempting to engage Canadians in a fair and just manner for hundreds of years. Unfortunately, these efforts often go unnoticed—even ignored—until flash-point events, culminations, or times of crisis occur. The winter of 2012-2013 was witness to one of these moments. It will be remembered—alongside the maelstrom of treaty-making, political waves like the Red Power Movement and the 1969-1970 mobilization against the White Paper, and resistance movements at Oka, Gustefson’s Lake, Ipperwash, Burnt Church, Goose Bay, Kanostaton, and so on—as one of the most important moments in our collective history. “Idle No More,” as it came to be known, was a watershed time, an emergence out of past efforts that reverberated into the future. The clear lesson regarding this brief note of context is that most Indigenous peoples have never been idle in their efforts to protect what is meaningful to our communities—nor will we ever be.

This most recent link in this very long chain of resistance was forged in late November 2012, when four women in Saskatchewan held a meeting called to educate Indigenous (and Canadian) communities on the impacts of the Canadian federal government’s proposed Bill C-45. The 457 pages of multiple pieces of legislation, an “omnibus” of new laws, introduced drastic changes to the Indian Act, the Fisheries Act, the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act, and the Navigable Water Act (amongst many others). Entitled Idle No More, this “teach-in” organized by Sylvia McAdam, Jess Gordon, Nina Wilson and Sheelah Mclean raised concerns regarding the removal of specific protections for the environment (in particular water and fish habitats), the improper “leasing” of First Nations territories, as well as the lack of consultation with the people most affected even where treaty and Aboriginal rights were threatened. With the help of social media and grassroots Indigenous activists, this meeting inspired a continent-wide movement with hundreds of thousands of people from Indigenous communities and urban centres participating in sharing sessions, protests, blockades and round dances in public spaces and on the land, in our homelands, and in sacred spaces.

From the perspective of our collective and based on the curated articles in this book, the Idle No More movement coalesced around three broad motivations or objectives:

- The repeal of significant sections of the Canadian federal government’s omnibus legislation (Bills C-38 and C-45) and specifically parts relating to the exploitation of the environment, water, and First Nations territories.

- The stabilization of emergency situations in First Nations communities, such as Attawapiskat, accompanied by an honest, collaborative approach to addressing issues relating to Indigenous communities and self-sustainability, land, education, housing, healthcare, among others.

- A commitment to a mutually beneficial nation-to-nation relationship between Canada, First Nations (status and non-status), Inuit, and Metis communities based on the spirit and intent of treaties and a recognition of inherent and shared rights and responsibilities as equal and unique partners. A large part of this includes an end to the unilateral legislative and policy process Canadian governments have favoured to amend the Indian Act.

Admittedly, the movement goes beyond even these issues. The creativity and passion of Idle No More necessarily revealed long-standing abusive patterns of successive Canadian governments in their treatment of Indigenous peoples. It brought to light years of dishonesty, racism and outright theft. Moreover, it engaged the oft-slumbering Canadian public as never before. Within four months, Idle No More moved beyond the turtle’s continental back and became a global movement with manifold demands.

Idle No More is, in the most rudimentary terms, a culmination of the historical and contemporary legacies emerging from colonization and violence throughout North America and the world. These involve land theft, treaty violations, and many misunderstandings. There is therefore much to talk about, reflect upon, and take action to redress. In this way, Idle No More represents a unique opportunity: a chance to deepen everyone’s understanding of the circumstances and choices that have led to this time and place; and a forum for how we can come up with solutions together. This movement represents an important moment for conversations about how to live together meaningfully and peacefully, as nations and as neighbours.

That being said, the nature and enormity of Idle No More meant that it was sometimes bewildering in scope and complexity. As it grew, the movement became broad-based, diverse, and included many voices. There were those focused on the omnibus legislation, others who mobilized to protect land and support the resurgence of Indigenous nations, some who demanded justice for the hundreds of missing and murdered Indigenous women, and still others who worked hard to educate and strengthen relationships with non-Indigenous allies. Many did all of this at once. Idle No More adopted a radically decentralized character, having no single individual or group “leader.” Instead, communities would join together for distinct purposes, temporarily or for long-term activism. Events were local, regional, and wide-scale. This often confused and frustrated those (particularly in the media) who looked for the “voice” of the movement or somebody who could—or would—speak on behalf of all participants. Idle No More, however, was inherently different. It defied orthodox politics.

(more…)

Posted on April 3rd, 2014 in AK Authors!, Current Events

Javier Sethness-Castro, author of Imperiled Life: Revolution Against Climate Catastrophe, conducted a lengthy and pretty fascinating interview with Noam Chomsky on the ongoing environmental crisis, its capitalist causes, and what anarchism might contribute to a solution. We’ve included an excerpt below. You can read the whole interview on truth-out.org, or watch it in glorious living color here.

JC-S: You have described humanity as being imperiled by the destructive trends on hand in capitalist society – or what you have termed “really existing capitalist democracies” (RECD). Particularly of late, you have emphasized the brutally anti-ecological trends being implemented by the dominant powers of settler-colonial societies, as reflected in the tar sands of Canada, Australia’s massive exploitation and export of coal resources, and, of course, the immense energy profligacy of this country. You certainly have a point, and I share your concerns, as I detail in Imperiled Life: Revolution against Climate Catastrophe, a book that frames the climate crisis as the outgrowth of capitalism and the domination of nature generally understood. Please explain how you see RECD as profoundly at odds with ecological balance.

Noam Chomsky: RECD – not accidentally, pronounced “wrecked” – is really existing capitalist democracy, really a kind of state capitalism, with a powerful state component in the economy, but with some reliance on market forces. The market forces that exist are shaped and distorted in the interests of the powerful – by state power, which is heavily under the control of concentrations of private power – so there’s close interaction. Well, if you take a look at markets, they are a recipe for suicide. Period. In market systems, you don’t take account of what economists call externalities. So say you sell me a car. In a market system, we’re supposed to look after our own interests, so I make the best deal I can for me; you make the best deal you can for you. We do not take into account the effect on him. That’s not part of a market transaction. Well, there is an effect on him: there’s another car on the road; there’s a greater possibility of accidents; there’s more pollution; there’s more traffic jams. For him individually, it might be a slight increase, but this is extended over the whole population. Now, when you get to other kinds of transactions, the externalities get much larger. So take the financial crisis. One of the reasons for it is that – there are several, but one is – say if Goldman Sachs makes a risky transaction, they – if they’re paying attention – cover their own potential losses. They do not take into account what’s called systemic risk, that is, the possibility that the whole system will crash if one of their risky transactions goes bad. That just about happened with AIG, the huge insurance company. They were involved in risky transactions which they couldn’t cover. The whole system was really going to collapse, but of course state power intervened to rescue them. The task of the state is to rescue the rich and the powerful and to protect them, and if that violates market principles, okay, we don’t care about market principles. The market principles are essentially for the poor. But systemic risk is an externality that’s not considered, which would take down the system repeatedly, if you didn’t have state power intervening. Well there’s another one, that’s even bigger – that’s destruction of the environment. Destruction of the environment is an externality: in market interactions, you don’t pay attention to it. So take tar sands. If you’re a major energy corporation and you can make profit out of exploiting tar sands, you simply do not take into account the fact that your grandchildren may not have a possibility of survival – that’s an externality. And in the moral calculus of capitalism, greater profits in the next quarter outweigh the fate of your grandchildren – and of course it’s not your grandchildren, but everyone’s.

Now the settler-colonial societies are particularly interesting in this regard because you have a conflict within them. Settler-colonial societies are different than most forms of imperialism; in traditional imperialism, say the British in India, the British kind of ran the place: They sent the bureaucrats, the administrators, the officer corps, and so on, but the place was run by Indians. Settler-colonial societies are different; they eliminate the indigenous population. Read, say, George Washington, a leading figure in the settler-colonial society we live in. His view was – his words – was that we have to “extirpate” the Iroquois; they’re in our way. They were an advanced civilization; in fact, they provided some of the basis for the American constitutional system, but they were in the way, so we have to extirpate them. Thomas Jefferson, another great figure, he said, well, we have no choice but to exterminate the indigenous population, the Native Americans; the reason is they’re attacking us. Why are they attacking us? Because we’re taking everything away from them. But since we’re taking their land and resources away and they defend themselves, we have to exterminate them. And that’s pretty much what happened – in the United States almost totally – huge extermination. Some residues remain, but under horrible conditions. Australia, same thing. Tasmania, almost total extermination. Canada, they didn’t quite make it. There’s residues of what are called First Nations around the periphery. Now, those are settler-colonial societies: there are elements of the indigenous populations remaining, and a very striking feature of contemporary society is that, throughout the world – in Canada, Latin America, Australia, India, all over the world, the indigenous societies – what we call tribal or aboriginal or whatever name we use – they’re the ones who are trying to prevent the race to destruction. Everywhere, they’re the ones leading the opposition to destruction of the environment. In countries with substantial indigenous populations, like say in Ecuador and Bolivia, they’ve passed legislation, even constitutional provisions, calling for rights of nature, which is kind of laughed at in the rich, powerful countries, but is the hope for survival.

Ecuador, for example, made an offer to Europe – they have a fair amount of oil – to leave the oil in the ground, where it ought to be, at a great loss to them – huge loss for development. The request was that Europe would provide them with a fraction – payment – of the loss – a small fraction – but the Europeans refused, so now they’re exploiting the oil. And if you go to southern Colombia, you find indigenous people, campesinos, Afro-Americans struggling against gold mining, just horrible destruction. Same in Australia, against uranium mining; and so on. At the same time, in the settler-colonial societies, which are the most advanced and richest, that’s where the drive is strongest toward the destruction of the environment. So you read a speech by, say, Obama, for example, at Cushing, Oklahoma – Cushing is kind of the center for bringing together and storing the fossil fuels which flow into there and are distributed. It was an audience of oil types. To enormous applause, he said that during his administration more oil had been lifted than any previous one – for many, many years. He said pipelines are crossing America under his administration to the extent that practically everywhere you go, you’re tripping across a pipeline; we’re going to have 100 years of energy independence; we’ll be the Saudi Arabia of the 21st century – in short, we’ll lead the way to disaster. At the same time, the remnants of the indigenous societies are trying to prevent the race to disaster. So in this respect, the settler-colonial societies are a striking illustration of, first of all, the massive destructive power of European imperialism, which of course includes us and Australia, and so on. And also the – I don’t know if you’d call it irony, but the strange phenomenon of the most so-called “advanced,” educated, richest segments of global society trying to destroy all of us, and the so-called “backward” people, the pre-technological people, who remain on the periphery, trying to restrain the race to disaster. If some extraterrestrial observer were watching this, they’d think the species was insane. And, in fact, it is. But the insanity goes back to the basic institutional structure of RECD. That’s the way it works. It’s built into the institutions. It’s one of the reasons it’s going to be very hard to change.

[…] (more…)

Posted on April 1st, 2014 in AK Authors!

Persons in and around the Twin Cities area, two AK Press authors are in Minneapolis. You should see them, listen to them, and maybe even buy their books!

|

Kristian Williams, editor of Life During Wartime: Resisting Counterinsurgency.

Friday, April 4th 2014 at University of Minnesota

(hosted by Minnesota Global Justice Project)

1:30-3:00pm Room 614, Social Science Tower

Saturday, April 5th 2014 at Minnehaha Free Space

(hosted by Twin Cities Anti-Repression)

3747 Minnehaha Avenue S., Minneapolis, Minnesota 55406 |

|

Eric Laursen author of The People’s Pension: The Struggle to Defend Social Security Since Reagan

Monday, April 7th 2014 at Boneshaker Books

7:00pm, 2002 23rd Ave. S. MSP ~ One Block South of Franklin Ave. |