Posted on March 26th, 2010 in AK Distribution, Happenings

Just yesterday, AK Press received our first copies of the brand new book, Sistah Vegan. This is great timing because, well, it’s always great timing when a book on an important-but-underexplored topic comes out. It’s also great timing, though, because AK is gearing up to welcome editor Breeze Harper to our warehouse for a book release event in just a few weeks.

On Thursday, April 15th at 7pm, Ms. Harper will be here to read a passage from Sistah Vegan and talk about how whiteness manifests in the vegan and animal rights community, as well as the ways black women specifically speak to and against this. The intersection of critical race studies and veganism is a topic Breeze has a passion for, and one that clearly speaks to the identities and experiences of many others. Just ask any of the multitude of contributors to her book.

About the project, Breeze says in her own blog:

My research activism focuses on the under-researched topic of intersections of vegan philsophy and race/racism/racialized consciousness. My creation of Sistah Vegan came out of my desire to create a black female socio-spatial epistemological stance around veganism, simply because no one had ever done it before. When I would visit mainstream vegan forums, several years ago, veganism was only oriented toward animal rights as priority. However, a significant number of black female identified vegans that I had dialogued with had come to veganism from a completely different angle: reclaiming their womb health and fighting black health disparities. It was a clear indicator to me that the way one comes to, and engages in, veganism is heavily influenced by racialized and gendered experiences.

She’s also got more writing, and some very interesting videos up on subjects from “consumption and decolonial possibilities” to vegan hip hop and alternative black masculinities.

And if you’d like to do some further reading on the web, I’d highly recommend checking out the Vegans of Color blog. This is where I first heard about the Sistah Vegan project, and it is full of some of the most thoughtful discourse on intersectionality as it relates to veganism, animal rights, and food politics that I’ve come across.

I trust by now you’re thoroughly convinced to come to the warehouse, full of ideas and questions, on the 15th. If you’re the Facebooking type, you can view and RSVP to the event right here. And if for some reason you can’t make it out, be sure to check out the book, and follow Breeze’s journey with it on her blog. She may just be bringing the discussion to a bookstore, coffee shop, or community center near you.

Posted on March 24th, 2010 in AK Book Excerpts

Hi folks,

Hi folks,

For those interested in anarchism’s storied past—and curious as to what its future may hold—we are happy (ecstatic) to present Chris Ealham’s new book, Anarchism and the City: Revolution and Counter-revolution in Barcelona, 1898–1937. The following excerpt is from Chapter 6, “Militarised anarchism, 1932–1936,” which charts a period of insurrection, militarization, and expropriation for the CNT. Missing from below are thirty footnotes and a rose-colored-glasses view of the Barcelona working-class.

—

In an attempt to save the organisation from collapse, the armed groups within the orbit of the CNT and the FAI initiated new forms of fundraising. It is not certain from where the instruction emanated. It has been suggested that the FAI Peninsular Committee issued an appeal to the defence committees and its own grupos for money. Yet it is far from certain that the FAI had authority in such matters, and it is more likely that the order came from the Catalan CRT, which was ultimately responsible for the unions, press and prisoners’ welfare in the region. However, what we can be sure about is the fact that the recourse to illegal funding strategies cannot be explained solely in terms of the economic crisis of the CNT, for many revolutionary groups faced economic limitations on their activities during the 1930s and did not follow this path. Rather, it was the rise of the radical anarchists, for whom armed actions were central to all social protest, which sealed the switch to illegal fundraising tactics. Indeed, in much the same way as the radicals justified the illegality of the unemployed, so also did they rationalise that which funded the movement, drawing a sharp distinction between the term ‘robber’ and those who requisitioned money for ‘the cause’. Thus, just as the armed grupos were called upon to fill the vacuum left by the decline in CNT syndical muscle, so too were they required to secure the internal funding of the Confederation.

There was no single funding mechanism. In some cases, a form of ‘revolutionary tax’ was levied against employers and companies, who were informed of the sum involved (which depended on company size and which might run into tens of thousands of pesetas for large enterprises), the method of payment and the sanctions for non-payment, which ranged from the threat of sabotage against plant to the murder of managers. Since the authorities discouraged employers from meeting these ‘tax’ demands, it is difficult to know how often it was paid. We can nevertheless get a sense of how the ‘revolutionary tax’ operated from anecdotal evidence in the memoirs of managers and activists and from the press following the killing of employers for non-payment. There is also evidence that the ‘revolutionary tax’ was imposed on businesses that had been involved in strikes with the CNT and were thus held responsible for exhausting the resources of both the movement and their supporters. In l’Hospitalet, the Comité libertario pro-revolución social (Libertarian Committee for Social Revolution) levied the ‘tax’ on high-profile businessmen, such as Salvador Gil i Gil, a local councillor active in the repression of street traders.

Yet the most common method of funding was armed expropriation, normally involving attacks on banks and payrolls. As one militant explained, ‘to raid a bank was an episode of the social war’. Although, as we saw in Chapter 2, this strategy was used by anarchist groups after World War One, it was first utilised by CNT squads in the republican period during the wood workers’ strike (November 1932 to April 1933), when pickets punished intransigent employers by expropriating their cash boxes and safes. Sometimes, businesses owned by right wingers were also deliberately targeted. This funding tactic became highly attractive because, as one activist explained, ‘one well prepared attack and you get away with a sum of money equal to four weeks collections’. By 1934, expropriations were a recurring feature of urban life, sometimes bringing as much as 100,000 pesetas into union funds at a single stroke.

The expropriations presented Companys, who replaced the recently deceased Macià as president of the Generalitat at the end of 1933, with a sharp dilemma. On 1 January 1934, in accordance with the devolution programme specified by the Catalan Autonomy Statute, the Generalitat’s newly formed Comissaria d’Ordre Públic (Public Order Office) assumed responsibility for policing. Determined to demonstrate its competence in the realm of public order to a suspicious centre-right government in Madrid and a critical Lliga in Barcelona, the Generalitat increased ‘the drive to persecute robbers, murderers and wreckers’, fearing that anything less would give the impression that order had been lost. Responsibility for the new autonomous Catalan police rested with Josep Dencàs and Miquel Badia, Generalitat interior minister and Barcelona police chief, respectively. While apparently Catalanising the security forces, Dencàs and Badia, both of whom had close links with the quasi-fascist ERC youth movement, the escamots, politicised policing in a way that had never been seen before. Along with his brother Josep, Badia drafted the violently anti-CNT, anti-migrant escamots into the Catalan police; the Sometent was also purged and replaced by escamots. Meanwhile, Jaume Vachier, an ERC councillor and businessman, took charge of the Guàrdia Urbana.

Because the expropriations were viewed as a deliberate attack on Catalan institutions, the grupistas were now repressed without quarter. The legal sanctions applied against grupistas and expropriators were stern: anyone found in possession of explosives could expect a prison term of up to twenty-two years; armed robbery normally meant a sentence of between thirteen and seventeen years, while the crime of firing at the police was normally punished with nine years in jail. Yet this did not deter the expropriators, who compromised the key professional claim of the police – that the force detected crime – for if the grupistas were not detained in flagrante delicto they proved difficult, near impossible, to apprehend. In fact, when cornered, the expropriators, who were equipped with a range of weaponry, including pistols, sub-machine-guns and grenades, were a genuine match for the security forces. Following a payroll heist at a factory in central Barcelona, one grupo used guns and grenades to break through a police cordon and, when they were later intercepted by an asalto patrol in Santa Coloma, another gun battle ensued, after which the expropriators disappeared.

The elimination of the ‘cancer of banditry’ was a key factor in the evolution of the new autonomous police. Police Chief Badia, who was known to his admirers as Capità Collons (Captain Balls), took personal responsibility for the repression of the expropriators, regularly joining the front line during shoot-outs and picking up a number of gunshot wounds in the process. According to one Barcelona faísta who had connections in catalaniste circles, Badia planned to establish a special police unit dedicated to the extra-judicial killing of anarchists, an initiative that was blocked by the personal intervention of Companys, who feared the consequences of a return to the pistolerisme of the early 1920s. Nevertheless, Badia succeeded in raising the stakes in the war against the expropriators and the grupistas, adding a new viciousness to the history of policing in Iberia. Independent doctors regularly confirmed that suspected grupistas leaving the Comissaria d’Ordre Públic had been brutally mistreated and, according to anarchists and communists who had experience with the police during the monarchy and the Republic, the autonomous Catalan security forces were the most vicious of all. In one notorious case, following a shoot-out between police and an armed gang on the outskirts of the city, Badia left wounded ‘murcianos’ without medical treatment, and it was only after a heated argument with a Guardia Civil commander that an ambulance was called to the scene. There is also evidence that the Generalitat police adopted a policy of selective assassination of ‘FAI criminals’. The first suspicious death occurred in early 1934, when the body of a young faísta was found on wasteland on the outskirts of Barcelona. Although the deceased had apparently earlier participated in a gunfight with the police, the fact that he died from a single shot from a police-issue revolver suggested that he had been summarily executed. In a separate case, an unarmed cenetista was shot and killed in broad daylight by an off-duty policeman in a Les Corts street. Memories of 1920s police tactics were evoked again when an unarmed grupista was shot in the back after he allegedly ‘attempted to escape’. Meanwhile, in mid-April, after a gunfight in which over 200 rounds were exchanged, Bruno Alpini, an Italian anarchist and expropriator, was killed on Paral.lel in what was regarded in anarchist circles as a classic act of Ley de Fugas. The following month, two more expropriators were shot dead by police in the drive to ‘clean up’ Barcelona.

Despite intense police pressure, the number of expropriations showed no sign of abating throughout 1934 and 1935, demonstrating that increased policing does not necessarily reduce illegality. This very point was recognised in a police report published in the press in April 1935: ‘When a trial for robbery or an assassination occurs, immediately new robberies are committed…an established chain of punishable events.…It is this continuity that it is vital to break’. There are several reasons for this ‘continuity’. First, it was impossible for the authorities to provide a permanent guard for the numerous large sums of money transported around and concentrated within the city that were targeted by well-drilled and selective expropriators, who apparently launched attacks when they knew they had a good chance of escape. Moreover, since speed was one of the expropriators’ main allies, they used cars, often hijacked taxis or stolen from the rich, that they knew were faster than police models. The expropriators also recognised that, if they were injured, they would be looked after by the organisation and could receive medical attention from doctors supportive of the CNT–FAI.

Second, the expropriation squads were deeply rooted in the social formation and were virtually impossible for the police to infiltrate. Recruited from proven activists from the defence committees and the prisoners’ support committee, as well as some of the more willing and capable members of the grupos de afinidad, the expropriators were trusted individuals, many of whom during earlier, less repressive times had organised union collections in workplaces and barris. Some expropriators were ‘professional revolutionaries’ in the classic sense; they had experience of evading the police from the postwar years, possessed the necessary pseudonyms and false identities and tended to move around, staying with comrades and in ‘safe houses’. In a positive sense, this commitment to the movement explains the high level of probity among the expropriators, who also needed little reminder of the sanctions that would have been applied to anyone who attempted to abscond with the organisation’s money.

In addition to the unity derived from a common ideology and shared objectives, the expropriators also relied on the affective ties of kinship and neighbouring. Many expropriators were recruited from local families with a history of anarchist and union activism. Moreover, the family structure, so often associated with the stability of the existing order, frequently gave considerable coherence to the high-risk activities of the expropriators. In one squad, a father and son worked together. Meanwhile, Los Novatos, a grupo de afinidad active in funding initiatives, included five brothers from the Cano Ruiz family and two other sets of brothers, all of whom resided within a square kilometre of one another in the La Torrassa barri.

The esprit de corps that so typifies such close-knit groups ensured that, when the security forces succeeded in detaining members of a squad, they stubbornly refused to betray their comrades by talking to the police or by passing information on to the authorities. Indeed, detained grupistas relied on a version of omertà, repeatedly informing police that they had occasioned upon their accomplices in a bar or cafe, that they could not remember anything about their appearance and that they had failed to ask their names. Grupistas also frequently told police that these same strangers had lent them any arms they had in their possession at the time of their arrest, a completely unbelievable story concocted not to appear credible but to frustrate police investigations. Meanwhile, anyone who gave in to police pressure ran the danger of being perceived as a traitor, a perfidy that was dealt with in summary fashion.

A few other observations can be made about the expropriators. They were invariably male. Women rarely participated and, when they did, their involvement was almost exclusively of an auxiliary nature. The expropriators were also predominantly young and single. Even the more seasoned activists in the squads were normally under forty, while the most active expropriators of the 1930s were in their early twenties, such as Josep Martorell i Virgili, dubbed ‘Public Enemy Number One’ in the bourgeois press, who was only twenty when arrested, by which time he had launched a series of bank robberies for the CNT and for the anarchist movement.

The expropriations provide yet another example of the readiness of the anarchists to mobilise beyond the factory proletariat and channel the rebellion of those deemed unmobilisable by other left-wing groups. This was perhaps epitomised by the presence of several former detainees from the Asil Durán borstal among the expropriators, such as the aforementioned Martorell. The eclectic tactical repertoire of the anarchists, their continuing ability to combine ‘modern’ with older protest forms, increased the vitality of their resistance struggle, and, in equal measure, scandalised the ‘men of order’.

Posted on March 22nd, 2010 in AK Authors!, Happenings

That’s a nice title for a post, huh?

Two members of the Void Network from Greece and one US comrade were in the bay area recently, where they gave a series of kick-ass talks. The occasion for their visit (and their extensive US tour) was the publication of We Are an Image from the Future: The Greek Revolt of December 2008, just released by AK Press.

Two members of the Void Network from Greece and one US comrade were in the bay area recently, where they gave a series of kick-ass talks. The occasion for their visit (and their extensive US tour) was the publication of We Are an Image from the Future: The Greek Revolt of December 2008, just released by AK Press.

The illustrious dave id of Indybay wrote a nice review of their event at the BASTARD conference (that’s the Berkeley Anarchist Students of Theory and Research and Development, in case you were wondering). And he also provided an audio link to their entire hour-and-fifteen-minute talk, which you can listen to below. It seemed to be an amazing and inspiring experience for everyone who attended, so I highly recommend giving it a listen.

If you missed the talk and/or are blown away by the audio link below, don’t despair. The “We Are an Image from the Future Tour” has about three dozen more events planned for cities around the country…with more to be added. You can check out their schedule here.

Here’s the audio:

Posted on March 20th, 2010 in AK Allies

The Left Bank Books collective is going to have to (very temporarily) close up shop this fall. Here’s how you can help:

—-

Friends of Left Bank Books!

Friends of Left Bank Books!

As you (hopefully) know, Left Bank Books is still alive and well, after 36 years in the Pike Place Market. We are still run collectively, and we still carry a wide variety of general books, while specializing in left-wing and anarchist materials.

HOWEVER—as you know, several independent bookstores have folded recently, both because of the economic crash, and competition from Amazon, etc. The demise of independent bookstores would also spell the demise of small presses, whose publications are ignored by the corporate chains.

Left Bank is facing an extra challenge as well: Our building will undergo earthquake retrofitting sometime this fall. We will be forced to close for up to three months. We have never closed before, and we are determined to reopen ASAP!!

WE NEED YOUR SUPPORT TO HELP US SURVIVE! In these hard times, we don’t want to ask for donations. But what would help enormously is this:

Purchase a Left Bank Gift Certificate before we close. Keep it for yourself, or gift it to a friend. If enough people do this, we will be able to save in advance some of the revenue we will lose during the closure. With that money, we will be able to pay our ongoing expenses, while building up our stock of great books for our re-opening.

You have several options: You can come into the store and buy the gift certificate. You can send a check in the amount you want to spend, and we will mail the GC to you. You can call in your request, and pay with a credit card.

Above all, you can pass this letter on to everyone you know who would care about the ongoing success of Left Bank. That’s 36 years of people! No need to stop at the borders of Seattle—if people don’t mind spending part of their gift certificate on postage, we will happily mail books to them.

In Solidarity,

The Left Bank Collective

Left Bank Books

92 Pike Street (corner of First and Pike)

Seattle, WA 98101

(206) 622-0195

Posted on March 19th, 2010 in About AK, AK News

The AK Press Oakland warehouse crew got a surprise workout yesterday when a truck arrived from our printer carrying five pallets of quality literature for you, dear readers. And so we offer you this photographic evidence of our truck-unloading prowess. We did it all for you—and with the help of some smooth pallet-jack maneuvers by the truck driver, Jack (unfortunately not pictured but still dear to our collective heart).

Among the boxes we unloaded were our warehouse stock of our exciting new titles We Are An Image from the Future and Anarchism and Its Aspirations (which, have we mentioned?, you will still get this month, along with Anarchism and the City, if you sign up as a Friend of AK Press today!). We also got reprints of several of our more popular titles—My Mother Wears Combat Boots, Pacifism as Pathology, No Gods No Masters, and SCUM Manifesto. Whew!

|

|

AK Press muscleheads (L-R) Bill, Ashley, Kate (visiting us from Baltimore!), Victoria, and Macio celebrate victory over the truck of books.

|

Posted on March 18th, 2010 in Happenings

What, don’t recognize that acronym?

I’m talking, of course, about the San Francisco Bay Area Anarchist Bookfair. The 15th annual, actually, which the entire AK collective attended this past weekend.

Since we’ve already dedicated two blog posts telling you about the event in advance, and listing the incredible lineup of AK authors and allies who spoke, I’m going to keep this one short on text. We’ll call it a photo essay. You’re welcome.

A couple things I can’t let just slip by, despite my promise to shut up at the beginning of this post:

First, did you see our new shirts? There’s a semi-close up of the four of them up there, all designed by our friend John Yates, and all completely effing awesome, if you ask us. Bookfair patrons got the first go at ’em, but lucky for you, dear internets, all are now available on our website.

Also, we were delighted to debut our three (count ’em!) new AK books: Anarchism and Its Aspirations, We Are an Image From the Future, and Anarchism and the City. All received a very warm welcome, of course.

And finally, we want to extend a thank you to all our hardworking volunteers (including Jeff, pictured above reigning over the sale table, as he has for all of eternity, as far as I’m aware.), and all the folks who show up year after year, to talk to, inspire, and support us at the SFBAABF. You guys are the best!

Posted on March 17th, 2010 in AK Authors!, Happenings

Those of you attending the Left Forum this year in New York should, as always, stop by the AK Press table and say hi. You’ll also have a chance to check out several AK authors who are giving talks. Here’s the lowdown:

Left Forum 2010

THE CENTER CANNOT HOLD:

Rekindling the Radical Imagination

March 19-21

Pace University

One Pace Plaza

New York, NY 10038

Session 1: SATURDAY, 10:00 AM – 12:00 PM

Post-Identity Politcs

W-615

Kevin Alexander Gray – Author of Waiting for Lightening to Strike: The Fundamentals of Black Politics

Lessons from Latin American Social Movements for a US in Crisis

W612

Ben Dangl – Author of The Price of Fire: Resource Wars and Social Movements in Bolivia

Marina Sitrin – Editor of Horizontalism: Voices of Popular Power in Argentina

Session 2: SATURDAY, 12:00 PM – 2:00 PM

Reimagining Society: The Nature of the Task

Schimmel

Chris Spannos (Chair) – Editor of Real Utopia: Participatory Society for the 21st Century

Michael Albert – Author of Moving Forward: Program for a Participatory Economy

Session 3: SATURDAY, 3:00 PM – 5:00 PM

A Panel Discussion on Anarchism and Marxism

W510

Cindy Milstein – Author of Anarchism and Its Aspirations

Envisioning Real Utopias

W612

Peter Staudenmaier – Co-author of Ecofascism: Lessons from the German Experience

Envisioning Self-Governance

E328

Cindy Milstein – Author of Anarchism and Its Aspirations

Academic Repression Book Talk

W602

Theory and Action

A panel of contributors to Academic Repression: Reflections from the Academic Industrial Complex

Anthony J. Nocella, II (Chair)

Liat Ben-Moshe and Dr. Caroline Kaltefleiter

Victoria Fontan

Deric Shannon

Rethinking the National Question in the United States

W610

Fred Ho – Editor of Legacy

Ten Years Later: Organizers Reflect on the 1999 Seattle WTO Protests

W507

Chris Dixon (Chair) Contributor to The Battle of the Story of “The Battle of Seattle”

Horizontalism and Grassroots Democracy in the Americas

W503

Marina Sitrin – Editor of Horizontalism: Voices of Popular Power in Argentina

(more…)

Posted on March 17th, 2010 in AK Authors!, AK News, Happenings

As many of you know, some of the editors of AK’s amazing new book on the Greek Insurrection of 2008 are here in the US this month (and next) on a tour to promote the book and build solidarity between activists and anarchists in Greece and the United States.

As many of you know, some of the editors of AK’s amazing new book on the Greek Insurrection of 2008 are here in the US this month (and next) on a tour to promote the book and build solidarity between activists and anarchists in Greece and the United States.

Last night, the window of their borrowed car was smashed while it was parked in a quiet Berkeley neighborhood, resulting in the loss of hundreds of dollars of books, pamphlets, videos, and other merchandise, as well as a video projector and a number of external hard-drives and other electronic equipment. On top of the cost of gas and travel across the US and back again, this is a staggering financial blow.

The Greeks need your help to continue the tour, and recoup their losses (especially the video projector, which was owned by their collective in Greece). If you are able to make a donation to help defray the expenses of window repair, and replacement equipment and stock, please do so! Your donation would be greatly appreciated – any and all donations received through the button below will go directly to our Greek friends. Please help out if you can!

The Greeks need your help to continue the tour, and recoup their losses (especially the video projector, which was owned by their collective in Greece). If you are able to make a donation to help defray the expenses of window repair, and replacement equipment and stock, please do so! Your donation would be greatly appreciated – any and all donations received through the button below will go directly to our Greek friends. Please help out if you can!

Posted on March 16th, 2010 in AK Allies, Anarchist Publishers

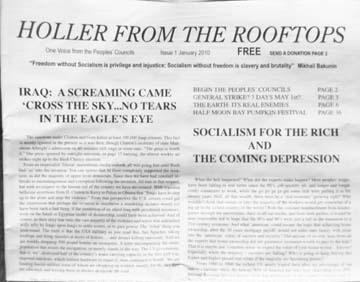

A new agitational paper is circulating around the bay area: Holler From the Rooftops. Long-time anarchist rabble-rouser Tommy Strange is at the helm. Tommy’s not the guy at every meeting and gathering, not the guy “on-the-scene” making a name for himself, he doesn’t travel the country going from book fair to book fair. When he says “ I don’t back down and I haven’t gotten soft,” he’s not full of shit. I invited Tommy to some anarchist meetings a while back and he told me, “I want action, I don’t wanna go to school.” How could I argue?

Here’s a link to some of the content from the first issue. Hopefully folks out there will see fit to contribute to the paper; not for Tommy’s sake, but because he’s bottom-lining a new (tried and true?) way to communicate our views to potential comrades. There’s a whole world to win, and Tommy’s not gonna get bogged down debating each and every nuance of your favored political persuasion. As every decent anarchist paper has done throughout history, Holler seeks to make our ideas known and accepted by those outside our circles, while holding the line.

To get a copy. contact Tommy (POB 40656, SF, CA 94140) or ask for one to be included in your next AK order. We’ve got a bundle or two that we’re including in mailorder shipments as you read this.

Why a local newspaper? Why now?

A free newspaper is the only way I see an individual reaching out to complete strangers, outside of the internet, and building some coherent base of radical face-to-face democracy. If you sell it, it ends up in only certain bookstores, and only certain people will pick it up. It’s not something I think I should be doing with my inability to write journalistic concise articles, or that I think I will excel at, but it’s a push forward for myself personally, even if only as an act of desperation. It is not simply a venue for news, facts, and horrors that the media leaves out—though on the surface that may appear to be its purpose—but a connecting point for strangers to make some attempt at bottom-up resistance.

What’s the editorial vision for the paper? Where is Holler from the Rooftops coming from? And whom do you see as the audience?

If I don’t quit—as I consider every other day, since I have that American infection of desiring immediate gratification—I would like it to be a left socialist/anarchist venue for what tiny portion of the masses that it can reach. Perhaps a mixture of the Anderson Valley Advertiser or Counterpunch, mixed with the urgency of old time anarchist papers such as the Masses and Rocker’s Arbeter Fraynd. As an editor, my main goals would be to find ten or more people to contribute, create a lengthy letter section, and act as a filter on a hard-line libertarian socialist viewpoint.

There are not many choices, many ways to look at history or present day problems, or two sides to every story. There is only one ethical “common ground” in which I view the choices for the future, and it is certainly not original, nor is it a naïve, unsubstantiated belief in human needs or human nature. I find no value whatsoever in presenting a Trotskyist or Leninist version of socialism, or revolution. The letters section is another thing. I will print many views there.

On the look of the first issue though, the paper definitely needs more workers’ voices that are not barking this intransigent view, but speaking from experience and the heart.

The last thing I want it to be is Tommy’s monthly rant, which the first issue is.

The audience is meant to be the workers, small business owners, people who still might even, after all the shit that is coming down, call themselves middle class….who have come to the obvious conclusion that there has to be another future, and we have to start building the road now. As I have handed out hundreds to complete strangers, and seen surprise and interest, I would say my overuse of the word “atomization” is not wrong. We live among millions in the USA that are just so sick of the experts and politicians, and in the past twenty years, due to great left book publishers and the internet, there are millions educated about how change really comes about. I don’t believe this paper will have anything to do with a large “spark.” I’m too cynical for that. But I do believe I have to try to create some kindling. To predict what is going to happen shortly in our lives, can either be a cynical intellectual exercise that brings on despair and inaction, or it can be a reasoned and optimistic heartfelt outlook that demands all contact possible to find real community based on physical proximity and common desires.

Your intention is for Holler to become a monthly paper. Tell us about the local independent and radical media in SF and what a paper like yours has to offer.

There is no mass radical print in the bay area. A strange thing in itself. There are tens of thousands in the bay area doing amazing organizing work, mutual aid, and education projects. The people here have the hearts and minds capable even of a long general strike against the wars. I doubt I can spark that. And I can’t change the defeatist “it can’t happen here” mindset absorbed from the ruling class’ and elites’ propaganda, among a large enough number of people. …I don’t think so anyway… More simply, it is a tangible thing you or I can pass on. Thirty percent of the country doesn’t even go on the web still, let alone to far left discussion forums. Yes, I have a problem with people relying on the internet thing as a main source of discussion. I’ve spent years in discussion forums online. Outside of its indispensable use as a great organizing avenue for actions and its obvious use as a source of information and cheap fast communication, when it comes to a “discussion forum,” …I find it dogmatic and flywheel and most often dominated by men who have too much time on their hands…(myself included for years). There is nothing comparable to face-to-face democracy. It creates responsibility and human bonds: comradery comes from the socialistic desires inside all of us. Typing alone is typing alone. (more…)

Posted on March 13th, 2010 in AK Authors!, Happenings

It’s shaping up to be a great spring; we’ve got authors out on the road promoting their new books every month from now through the fall … so stay tuned for tour details for Seth Tobocman, Ben Dangl, AK Thompson, Tricia Shapiro, Cindy Milstein, Jeff Coant, Void Network, Team Colors, and more!

In the meantime, our friends in the Pacific Northwest and Ontario have got a great couple of weeks ahead of them: Matt Hern tours the NW next week, and Michael Schmidt, South African co-author of the excellent Black Flame, tours Ontario, with the help of Common Cause. Check out the full schedules below!

And, note: we’re currently looking for funding to bring both Lucien van der Walt (Black Flame) and Raul Zibechi (Dispersing Power) to the US this summer/fall. So please get in contact if you happen to work with an organization or a university that might be willing to cover travel costs for either of these

folks!

Matt Hern in the Pacific Northwest

Starting with his appearance this Sunday (March 14) at the 15th Annual Bay Area Anarchist Bookfair, Matt Hern, author of AK’s new Common Ground in a Liquid City: Essays in Defense of an Urban Future, and editor of Everywhere All the Time: A New Deschooling Reader, takes to the road for a quick tour up the Pacific Coast. If you’re in Portland, Olympia, Seattle, or San Francisco, be sure to come on out and meet Matt!

Starting with his appearance this Sunday (March 14) at the 15th Annual Bay Area Anarchist Bookfair, Matt Hern, author of AK’s new Common Ground in a Liquid City: Essays in Defense of an Urban Future, and editor of Everywhere All the Time: A New Deschooling Reader, takes to the road for a quick tour up the Pacific Coast. If you’re in Portland, Olympia, Seattle, or San Francisco, be sure to come on out and meet Matt!

Sunday, March 14 | Matt Hern in San Francisco

Bay Area Anarchist Bookfair, 11:30AM

SF County Fair Building, Ninth Avenue and Lincoln Way, at Golden Gate Park

Studio for Urban Projects, 7-9PM

3579 17th Street, San Francisco

Monday, March 15 | Matt Hern in Seattle, WA

Left Bank Books, 7PM

92 Pike Street, Seattle

Tuesday, March 16 | Matt Hern in Olympia, WA

Orca Books, 6PM

509 4th Avenue East, Olympia

Wednesday, March 17 | Matt Hern in Portland, OR

The Red & Black Cafe, 7PM

400 Southeast 12th Avenue, Portland

*****

Michael Schmidt in Canada

South African journalist Michael Schmidt heads to Canada next week for a week-long tour of Ontario to promote Black Flame: The Revolutionary Class Politics of Anarchism and Syndicalism, organized by the wonderful folks at Common Cause. Be sure to check out one of Michael’s events if you’re in the area!

South African journalist Michael Schmidt heads to Canada next week for a week-long tour of Ontario to promote Black Flame: The Revolutionary Class Politics of Anarchism and Syndicalism, organized by the wonderful folks at Common Cause. Be sure to check out one of Michael’s events if you’re in the area!

Monday, March 15 | Michael Schmidt in Waterloo

Wilfrid Laurier University, 4-6PM

School of Business and Economics, Room 2260

75 University Avenue West

(Sponsored the Communication Studies and Global Studies departments.)

March 16 | Michael Schmidt in London, details tba

March 17 | Michael Schmidt in Hamilton

McMaster University, 12-2pm

MUSC Rooms 311 and 313

1280 Main St. West

Limited seating.

Please RSVP at commoncauseontario@gmail.com

(Sponsored by the LIUNA-Mancinelli Professorship in Global Labour Issues and the School of Labour Studies.)

Sky Dragon Centre, 7-9pm

27 King William Street

Hamilton, ON

Organized by Common Cause Hamilton

commoncausehamilton@gmail.com

March 18 | Michael Schmidt in Montreal, details tba

March 19 | Michael Schmidt in Ottawa

University of Ottawa 3:00pm

Desmarais Building room 3120 (DMS)

(the newer building at ‘Laurier Station’ on the Transitway)

Exile Infoshop 7pm

256 Bank St, 2nd floor

(at the corner of Bank and Cooper)

March 20 | Michael Schmidt in Toronto

University of Toronto, 3-5PM

Bahen Centre, Room 1220

40 St. George Street

(Co-sponsored by the Pan African Solidarity Network and the Work and Labour Studies Programme, York University.)

Keep an eye out for updates at linchpin.ca, or email Common Cause at commoncauseontario@gmail.com.

PLUS! I almost forgot … the folks at Common Cause have made a promotional web video for Michael’s tour, making Black Flame the first book (I think) to have it’s own promo video. How cool is that? Stay tuned for more exciting forays into the world of 21st century technology … and enjoy the video!

Two members of the Void Network from Greece and one US comrade were in the bay area recently, where they gave a series of kick-ass talks. The occasion for their visit (and their extensive US tour) was the publication of

Two members of the Void Network from Greece and one US comrade were in the bay area recently, where they gave a series of kick-ass talks. The occasion for their visit (and their extensive US tour) was the publication of  Friends of Left Bank Books!

Friends of Left Bank Books!