Posted on July 1st, 2009 in About AK, Spanish

Hace 20 años, AK Press fue fundado oficialmente como un colectivo en Escocia. El colectivo pudo sobrevivir a esos primeros años gracias a la energia de sus fundadores, en especial Ramsey Kanaan y al apoyo de todos los anarquistas a través del Reino Unido, quienes estaban muy ansiosos esperando ver florecer nuestras ideas.

En 1994, Ramsey se traslado a Bay Area (USA) para empezar una nueva sucursal de AK Press. En esos años, AK Press ya tenia oficinas en Edinburgh y Londres, esta ultima actualmente cerrada, pero aún contando con el apoyo de sus fundadores en distintas tareas. Desde entonces, las sucursales de USA y del Reino Unido han funcionado con sus propias redes de distribución (las cuales no están ligadas financieramente) y colaborando en la edicion de nuevos proyectos como un gran colectivo. Cada año nos reunimos para nuestra Reunion General Anual (RGA) para discutir sobre negocios, el estado actual del movimiento y, lo más importante, sobre los próximos proyectos editoriales. La idea original de estas reuniones era que cada año fueran en un país distinto, pero desechamos esa idea al ver que el colectivo en USA crecia y en el Reino Unido cada dia se hacia más pequeño. Ahora estas reuniones solamente las hacemos en Bay Area.

Bueno, despues de muchos años tuve la oportunidad de visitar a Lex y Mike. Junto a Lorna pasamos unos dias en AKUK para ponernos al dia sobre las actividades del colectivo, y tambien para beber cerveza escocesa y visitar sus lujosas oficinas. Lex ha sido parte de AK Press desde sus inicios y Mike lleva mas de una década trabajando con nosotros. Como pueden ver en las fotos, tienen la misma dedicación a tener un entorno de trabajo ordenado tal como sus compañeros Norteamericanos.

Los ultimos proyectos de nuestras oficinas en UK fueron los libros Rebel Alliances de Benjamin Franks y el Volumen I de An Anarchist FAQ. Actualmente se encuentran trabajando en el Volumen II de An Anarchist FAQ y estan haciendo los preparativos para una nueva edicion de Proudhon con Iain McKay.

[Traducción: Bruno Battaglia]

(more…)

Posted on June 27th, 2009 in AK Allies

The death of Edgar Rodrigues in May was a major blow to the anarchist movement in Brazil and also around the world. Though it would be unrealistic to try to capture the richness and complexity of his life in a single essay, an attempt must be made nonetheless.

The following article by Marcolino Jeremias makes such an attempt. It was translated by Chuck Morse. The piece is available in Spanish here and in Portuguese here.

* * *

An Attempt to Say Goodbye: On the Life and Work of Edgar Rodrigues

Antônio Francisco Correia, who used the pseudonym Edgar Rodrigues, was born to Manuel Francisco Correia and Albina da Silva Santos on March 12, 1921 in Angeias, which is north of the city of Matosinhos in the Portugual’s Portu district. His father was a militant anarcho-syndicalist and participated in the “Union of the Four Arts,” an affiliate of the Confederación General del Trabajo (CGT) and the International Association of Workers (AIT), which represented various workmen’s trades in Matosinhos. Two cousins, Armindo da Silva Sarilho and Manuel Sarilho, were also members of the Union.

Toward the end of 1933, a crackdown by Antônio Oliveira Salazar’s military dictatorship forced the closure of this union. Part of its cultural archive was hidden in the Correia family home and clandestine administrative meetings were also held there in the evening hours. The young Antônio Francisco Correia listened with great curiosity to the discussions held during the gatherings.

State police raided the home one early morning in 1936 and arrested Manuel Francisco Correia. Antônio Francisco Correia—or “Correia,” as he was known among intimates—often visited his father in the political police lockup during the ten weeks that he was imprisoned there without trial. Once freed, his father was punished anew by being deprived of his job, which caused the family to endure serious economic difficulties.

Two years later, Correia wrote his first article for Portu’s Primero de Enero newspaper, although it was not published due to censorship. At this time, he also began to compose the drafts that would make up his first book.

On May Day, 1939, Correia and some friends skipped work as a form of protest—it was illegal to commemorate May Day—and met to affirm the anarchist origins of the date. In March of the following year, he joined the Flower of Youth Drama Group (Theater Lover) of Santa Cruz Bispo in the Matosinhos municipality, where he met Ondina dos Anjos da Costa Santos, who became his life-long partner. He also worked with the Joys of Perafita Drama Group, where he met the militant anarchist historian, José Marques da Costa.

In September 1946, the anarchist Luis Joaquim Portela[1] and five political prisoners escaped from the Peniche Fortress. Two years later, Correia met Portela while he was underground and helped him acquire forged documents, although it so happens that he was imprisoned again due to a betrayal.[2]

On July 19, 1951, he was introduced to the infamous anti-clerical writer Tomás da Fonseca and, the following day, set off for Brazil in flight from political persecution unleashed by the Portuguese dictatorship.

Upon arriving in Rio de Janeiro, he met the following comrades: Roberto das Neves, Manuel Perez, Giacomo Bottino, Ida Bottino, Germinal Bottino, Pascoal Gravina, José Romero, Ondina Romero, Angelina Soares, Diamantino Augusto, José Oiticica, João Peres Bouças, Carolina Peres, Ideal Peres, and Afonso Vieira among others…

At the prompting of Perse and Vieira, he submitted an article that he had authored on the Portuguese dictatorship that was published in the anarchist periodical Acción Directa[3] and later became active in the publishing group by the same name. Immediately thereafter, with the help of comrades such as Enio Cardoso, Domingos Rojas, and Benjamim Cano Ruiz, he began publishing essays in the international libertarian press and also, as this time, adopted the pseudonym Edgar Rodrigues.[4]

He participated in the gathering of the Brazilian anarchist movement that occurred on February 9-11, 1953 in the home of José Oiticica. At this meeting, he met other anarchist militants who were active in São Paulo: Edgard Leuenroth, Adelino Tavares de Pinho, Lucca Gabriel, Osvaldo Salgueiro, to name a few. During this period, he also met the Spanish writer and journalist Victor Garcia (Tomás-Germinal Gracia Ibars), Romanian poet Eugen Relgis, and Paraguayan comrade Ceríaco Duarte.

(more…)

Posted on June 27th, 2009 in AK Allies, AK Authors!, Spanish

Los estudios sobre los movimientos radicales suelen ser muy detallados o muy generales. Usualmente, estamos obligados a elegir entre los árboles o el bosque.

Los estudios sobre los movimientos radicales suelen ser muy detallados o muy generales. Usualmente, estamos obligados a elegir entre los árboles o el bosque.

Gracias a The International Encyclopedia of Revolution and Protest esto no volverá a suceder. Esta edición consta de 8 volúmenes que exploran la historia de los movimientos revolucionarios y de protesta durante los últimos 500 años. Aparte de la edición como libro, existe además una edición online de estos volúmenes. Te pedimos que consideres conseguir este libro para tu biblioteca local o universitaria, y por otro lado ver la opción de suscribirte a su edición online.

Además, estamos muy felices de anunciar que incluye una extensa cobertura al movimiento anarquista y sus pensadores, gracias al esfuerzo de Jesse Cohn. Entre los otros colaboradores, podemos encontrar a autores que han colaborado con AK PRESS de alguna manera. Entre estos autores tenemos a Chris Carlsson, Benjamin Franks, Chuck Morse, y Lucien van der Walt.

[Traducción: Bruno Battaglia]

Posted on June 22nd, 2009 in AK Allies

Our pals at justseeds.org recently posted an interesting piece about Chicago artists who partnered with the Tamms Year Ten coalition to protest state-sanctioned torture at the supermax prison in Southern Illinois. They launched a city-wide stenciling campaign…and the medium was mud.

Our pals at justseeds.org recently posted an interesting piece about Chicago artists who partnered with the Tamms Year Ten coalition to protest state-sanctioned torture at the supermax prison in Southern Illinois. They launched a city-wide stenciling campaign…and the medium was mud.

As the post notes, “mud-stenciling” has two main advantages: “Mud as a medium is especially sensible for artists and activists who want to work outdoors with a non-toxic substance to reach a large public audience. Moreover, city governments and law enforcement agencies have little precedence in dealing with mud stencils so there is a gray area on whether it is legal or not.”

So, any of you radical artistes out there who are looking for a new ways to reach the masses should head over to justseeds.org. Well, aside from mud-stenciling, you should check them out often, because there are always new ideas and approaches being broadcast on their site.

Posted on June 20th, 2009 in AK Authors!, Recommended Reading

Histories of radical movements tend to be either way too detailed or way too general. Typically, we’re forced to choose between the forest and trees.

Histories of radical movements tend to be either way too detailed or way too general. Typically, we’re forced to choose between the forest and trees.

That may no longer be the case thanks to the appearance of The International Encyclopedia of Revolution and Protest, a massive, eight-volume work that explores the history of protest and revolution over the past 500 years. In addition to the hard copy edition, there is also a searchable online edition here. Please consider getting your local public or university library to purchase the book and/or subscribe to the online database. It’s very impressive.

We are also happy to report that it contains extensive coverage of anarchist movement and thinkers, due primarily to the efforts of Jesse Cohn. Among the contributors of entries on anarchism, you will find authors who have had been associated with AK Press in one way or another, including Chris Carlsson, Benjamin Franks, Chuck Morse, and Lucien van der Walt.

Posted on June 17th, 2009 in Reviews of AK Books

We LOVE it when people review AK Press books. The following review by Abe Walker first appeared in the May 2009 issue of the CUNY Graduate Center Advocate.

* * *

“No War But Class War”

Book Review by Abe Walker

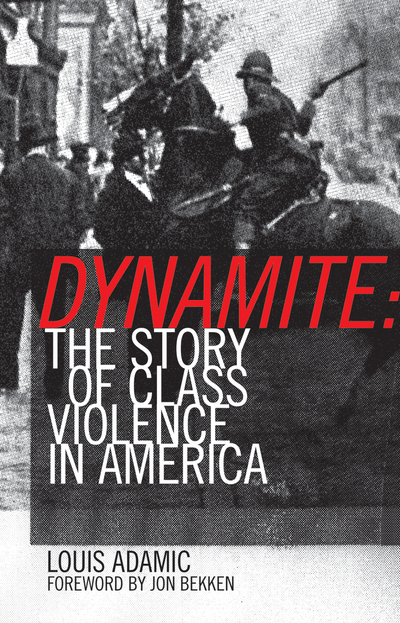

Dynamite: The Story of Class Violence in America by Louis Adamic. AK Press Edition (2008)

The contemporary US labor movement does not have a reputation for militancy. By almost any standard, American unions stack up poorly compared to their European, Asian, African and Latin American counterparts. American workers strike less often than workers almost anywhere else in the world, and the total number of days lost to work stoppage as a percentage of total days worked is embarrassingly low. The Bureau of Labor Statistics recorded only twenty-two major strikes in 2005. By comparison, in authoritarian China, where independent labor unions have no legal status and the strike weapon is outlawed, groups of workers walked off the job 19,000 times in 2005. When American workers do strike, they do it so quietly it rarely makes the news, and if the police get involved, it’s usually only to redirect traffic.

The contemporary US labor movement does not have a reputation for militancy. By almost any standard, American unions stack up poorly compared to their European, Asian, African and Latin American counterparts. American workers strike less often than workers almost anywhere else in the world, and the total number of days lost to work stoppage as a percentage of total days worked is embarrassingly low. The Bureau of Labor Statistics recorded only twenty-two major strikes in 2005. By comparison, in authoritarian China, where independent labor unions have no legal status and the strike weapon is outlawed, groups of workers walked off the job 19,000 times in 2005. When American workers do strike, they do it so quietly it rarely makes the news, and if the police get involved, it’s usually only to redirect traffic.

Given this, it’s easy to forget that 100 years ago, the American workplace was the site of perpetual, unmitigated violence. During the period extending roughly from 1886 to 1935, the conflict between labor and capital could be labeled a “class war” in more than a metaphorical sense. Labor rebellions were routinely put down by private company police, armed thugs-for-hire, state militias, the national guard, and in at least one instance, the United States Army itself. This story has been told and retold, in whole and in part, by numerous labor historians. But what’s striking about Louis Adamic’s Dynamite, originally written in 1934 and recently re-issued by AK Press, is that he stresses something the other historians know but refuse to admit: the violence was often two-sided.

This should be no surprise to any serious student of American history. The United States is a nation born of bloodshed, and there was a time when the Second Amendment had defenders others than right-wing extremists. But the other popular histories of American labor–such as Labor’s Untold Story, originally published by the Communist-led United Electrical Workers, and Jeremy Brecher’s Strike!–take the moral high ground by downplaying the violence of workers, while emphasizing the violence of the state. To be sure, in the frequent pitched battles that were waged during this period, labor casualties consistently outnumbered police and military casualties by a margin of at least ten-to-one (sometimes significantly higher). And wanton acts of cruelty, like the 1914 Ludlow Massacre where hundreds of striking miners and their families were gunned down in cold blood, were the exclusive domain of the state. Clearly, it would be wrong to suggest that workers were the primary instigators of violence. But it would be equally wrong to depict the workers as poor, defenseless victims, armed with nothing but their moral certitude and their historical prerogative. When attacked, workers readily fought back with fists, rocks, guns, incendiary devices, and organized bombing campaigns. To minimize or deny this reality is to distort the historical record.

The AK Press edition of Dynamite includes a foreword by Jon Bekken, an activist and organizer with the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). Bekken briefly situates the text in its historical context, but his main intellectual project is apparently to defend the legacy of his own organization. The IWW receives significant attention in the text, and Adamic’s assessment is mixed. Bekken quickly–though unconvincingly–refutes the suggestion that the IWW reciprocated the violence unleashed against them (well, except sometimes, but only in self-defense), and dismisses the assertion that sabotage was ever a major part of the IWW’s strategy. (The truth is probably more complicated. From 1912 to 1915, the union issued a series of pamphlets advocating sabotage, which it later disowned as the political climate grew more repressive. The contemporary organization distances itself from these pamphlets, which are displayed on its website alongside a bold disclaimer: “The following document is presented for historical purposes…workers who engage in some of the following forms of sabotage ri (more…)

Posted on June 17th, 2009 in AK News, Happenings, Spanish

Necesitas abastecerte de libros para este verano? No esperes más! Empieza AHORA, todo el material de nuestro website esta con un 20% de descuento. Esta oferta se extendera hasta el proximo Domingo 21 de junio, y hay muchisimos titulos de los cuales no podras esperar (o tambien no olvidar).

Ya lo sabes: Esta venta excluye a los productos que ya estan con un precio de venta. Los inscritos como Amigos de AK Press y los certificados de regalos no tienen derecho a este descuento. Los descuentos no pueden ser combinados. Nuestro website no puede aplicar los descuentos automaticamente, asi que tu tarjeta de credito sera PRE-AUTORIZADA por el monto total pero nosotros le restaremos el 20% antes de cargar tu tarjeta. La preautorizacion desaparecera despues de un par de dias.

Por favor, manda tu orden antes de las 11:59PM (PST) del Domingo 21 de junio y asi aprovechar este descuento!

[Traducción: Bruno Battaglia]

Posted on June 15th, 2009 in AK News, Happenings

Need to stock up on summer reading? Wait no longer! Starting NOW, everything on our website is 20% OFF! This sale will last through next Sunday (June 21st), but we have lots of great new stuff that you won’t want to wait for (plus, you wouldn’t want to forget!).

You know the drill: This sale excludes items that are already sale priced. Subscriptions to Friends of AK Press and gift certificates are not eligible for this discount. Discounts cannot be combined. Our website cannot automatically apply discounts, so your credit card will be PREAUTHORIZED for the full amount but we will subtract 20% before actually charging your card. The preauthorization will disappear after a couple of days.

Please place your order before 11:59PM (PST) on Sunday, June 21st to take advantage of sale pricing!

Posted on June 13th, 2009 in AK Allies

Although friends of AK come from all age groups, Anaya Lucia (pictured below) may be one of the youngest (and she is certainly one of the most adorable!!).

Born at 6:35 AM on April 5, 2009 in San Jose, Californina, she is the daughter of Adam W. and Virjinia J. Anaya Lucia, bienvenida a la vida!!

Posted on June 10th, 2009 in Reviews of AK Books

Oh, do we ever love it when people review AK books! Of course, we love the publicity that this gives our titles but, more than anything, we love the fact that people are wrestling with the ideas that they contain! That’s what it’s all about for us.

Dana Williams authored the following excellent review, which first appeared in the Peace Review.

* * *

Horizontalism: Voices of Popular Power in Argentina

Horizontalism: Voices of Popular Power in Argentina

Edited by Marina Sitrin, 2006, Oakland, California: AK Press. 251 pp. $18.95 (paper).

Reviewed by Dana Williams

University of Akron

Horizontalism is not just the first English-language account of the most recent social movements in Argentina. It is also an in-depth exploration of the ideas—prefigurative politics and direct democracy—driving those movements. Editor Marina Sitrin, considers a variety of topics in turn, including horizontalism, autogestion and recuperated factories, autonomy, creation, power, feminism, and protagonism. As the editor states in her introduction, many of the words currently used in Argentina’s movements—such as horizontalidad or autogestion—have no exact English translation, so she rightly keeps the original Spanish word and allows her subjects to explain the new words and their meanings. This approach is appropriate given the dramatic and quick changes taking place that require new language to describe.

Sitrin has compiled a book that has a structure that mimics the very thing it helps to explain. Horizontalism discusses the dramatic changes in social life in Argentina following a devastating financial crisis in 2001—changes that created wide-spread democratic, autonomous, self-determined, collective-minded, and empowering groupings and organizations—by the use of passionate and articulate oral histories. Following the premise of horizontalism, Argentina’s movements respect the diversity of participating voices, and this book’s characters provide an equally nuanced and diverse explanation of movement activities. Just like in their popular assemblies, the book’s subjects generally agree on what they describe, but there are large, healthy portions of comradely disagreement. Each interviewee contributes his or her own understandings of a variety of phenomena occurring in Argentina, ranging from the December 2001 rebellion, reclaimed and cooperative factories, and neighborhood assemblies, to a movement of unemployed workers, feminism, middle-class revolt, and horizontalism.

During the past few years, activist documentaries have been permeating the political left, films like The Fourth World War, The Take, and i: Argentina, Indymedia, and the Questions of Communication. These films have introduced English-speaking audiences to the upheaval taking place in this country and have favorably displayed the creative actions of everyday Argentinians for all to see. This book adds the necessary texture and analysis to the social revolution presented in the films. Who would not be inspired? Or at least shaken (and depending who you are, maybe even scared) to the bone? This social revolution is not one that is debated by arm-chair Marxists or heady intellectuals in the Ivory Tower. The revolution—and in some respects, Argentina’s very future—appears in the tight control of the movement participants themselves.

The book details the social revolution following the economic crisis of late-2001, and in doing so, reveals the new language and vision of Argentina’s social movements. Within the span of a few weeks, five successive governments disintegrated as countless thousands of citizens gathered outside the Presidential palace in Buenos Aires chanting “¡Que se vayan todos!” (“they all must go!”). People met by the hundreds on street corners and held meetings (assembleas) with their neighbors—by consensus—after reading chalked messages on sidewalks asking for people to converge at a certain time (horizontalidad). In these assemblies, neighbors discussed community problems and worked collectively to address needs unmet by conventional government. Workers who had been unemployed by corporations fleeing the ruinous economy decided to seize and cooperatize their former workplaces and run the machines themselves (autogestion). Other unemployed workers organized into small-trades with each other, while creating road blockades to prevent corporate trucks for carrying products and raw materials of Argentina out of the country (piqueteros). And families and whole communities occupied spaces as varied as abandoned land and bankrupt banks, turning them into squatter neighborhoods and community centers.

(more…)