Posted on April 17th, 2009 in About AK, Anarchist Publishers

Rob Ray’s recent blog post on Libcom about what he see’s as anarchist literature’s “failure to crack the mainstream” really resonated with me. In a nutshell, Rob says:

a) anarchist publishers are producing higher quality works as of late.

b) this increase in production standards hasn’t necessarily resulted in higher sales

c) distribution of our literature needs more fruitful outlets

d) anarchists need more resources to help them reach their readership

I’m not sure that the quality of anarchist publications has improved overall (design and readability is improving, editing and fact-checking are going in the right direction but we have a long way to go still). And I think sales have increased (again, for some, not others, but largely due to making publications available through mainstream channels). But I agree that it is always crucial for anarchist publishers to find better ways to distribute their materials and that it’s a great idea for us to share, and find new, resources to help everyone reach a wider readership. Cover design alone doesn’t move books, but some knowledge and experience about what does move them exists—there’s no need to reinvent the wheel. AK Press has been operating for almost two decades now under an assumption that anarchist ideas are not only worthy of being “in the mainstream,” but had better find a sizable following there (or else, um, there’s little hope in working toward an anarchist future).

I’m not sure that the quality of anarchist publications has improved overall (design and readability is improving, editing and fact-checking are going in the right direction but we have a long way to go still). And I think sales have increased (again, for some, not others, but largely due to making publications available through mainstream channels). But I agree that it is always crucial for anarchist publishers to find better ways to distribute their materials and that it’s a great idea for us to share, and find new, resources to help everyone reach a wider readership. Cover design alone doesn’t move books, but some knowledge and experience about what does move them exists—there’s no need to reinvent the wheel. AK Press has been operating for almost two decades now under an assumption that anarchist ideas are not only worthy of being “in the mainstream,” but had better find a sizable following there (or else, um, there’s little hope in working toward an anarchist future).

NAVIGATING THE “BOOK TRADE”

Firstly, Rob mentions that “Even with the best of organization [anarchist pub lishers] are having difficulty finding new places to stock [books, magazines] and hawk them around.” No doubt this seems increasingly true, but the picture is much broader than one might expect. The obvious place to start selling books is through the book trade. The good news is that almost anyone will carry your books (from Amazon to Barnes & Noble to City Lights)—if they feel that someone will wander in and buy them. So, since City Lights is a great bookstore and readily stocks radical literature, the big question is: who is going to buy our books from Barnes & Noble and the like? Well, to be honest, lots of people. In my opinion, the challenge is how to convince the B&N buyers that your book is going to sell (and hence it’s worth them stocking it). Well, that’s the icky marketing and publicity side of things. You want to gain access to these places? There’s two ways to do it: have convincing-enough marketing and publicity plans in place or buy your way in—large stores have “programs” where you can basically rent space in the store. Book stores are a business. Buying shelf space doesn’t guarantee sales for the publisher but it guarantees income for the store (Amazon has similar programs in place to “promote” your book for a fee). Amazon is the fastest-growing bookseller, hands down. They extract non-negotiable fees from AK’s main distributor (that we end up having to pay ourselves) just to sell through them. Wholesale distributors have similar plans in place to extract money from publishers and smaller distributors (in the form of warehousing fees, catalog fees, fees on books returned, etc.). It’s called business. You don’t like it? Neither do we, but that’s the playing field.

lishers] are having difficulty finding new places to stock [books, magazines] and hawk them around.” No doubt this seems increasingly true, but the picture is much broader than one might expect. The obvious place to start selling books is through the book trade. The good news is that almost anyone will carry your books (from Amazon to Barnes & Noble to City Lights)—if they feel that someone will wander in and buy them. So, since City Lights is a great bookstore and readily stocks radical literature, the big question is: who is going to buy our books from Barnes & Noble and the like? Well, to be honest, lots of people. In my opinion, the challenge is how to convince the B&N buyers that your book is going to sell (and hence it’s worth them stocking it). Well, that’s the icky marketing and publicity side of things. You want to gain access to these places? There’s two ways to do it: have convincing-enough marketing and publicity plans in place or buy your way in—large stores have “programs” where you can basically rent space in the store. Book stores are a business. Buying shelf space doesn’t guarantee sales for the publisher but it guarantees income for the store (Amazon has similar programs in place to “promote” your book for a fee). Amazon is the fastest-growing bookseller, hands down. They extract non-negotiable fees from AK’s main distributor (that we end up having to pay ourselves) just to sell through them. Wholesale distributors have similar plans in place to extract money from publishers and smaller distributors (in the form of warehousing fees, catalog fees, fees on books returned, etc.). It’s called business. You don’t like it? Neither do we, but that’s the playing field.

And none of this work is particularly gratifying, and certainly not glamorous. Further, it’s not generally thought of as “anarchist activity” by most.

DOING IT OURSELVES

Luckily, the established book trade isn’t our only source for reaching people. But how do we reach the vast number of  folks who never set foot into a bookstore and don’t troll Amazon for new books? AK Press reaches them by tabling at a variety of events, networking with other groups, and passing out catalogs. Certainly we endeavor to attend as many radical events as possible (see our Spring list here) but we also get out to places where our literature isn’t commonplace. Whether it’s the Barrio Bookfest in LA, the Sonoma County Book Festival, the Baltimore Book Festival, the San Diego International Book Festival, or The Crossroads of the West Gun Show (yes, two of us tabled there a few years back), we actually go out and talk to people. Sometimes we sell a lot of books, sometimes we don’t—but we always meet new people and do our best to turn them on to anarchist ideas.

folks who never set foot into a bookstore and don’t troll Amazon for new books? AK Press reaches them by tabling at a variety of events, networking with other groups, and passing out catalogs. Certainly we endeavor to attend as many radical events as possible (see our Spring list here) but we also get out to places where our literature isn’t commonplace. Whether it’s the Barrio Bookfest in LA, the Sonoma County Book Festival, the Baltimore Book Festival, the San Diego International Book Festival, or The Crossroads of the West Gun Show (yes, two of us tabled there a few years back), we actually go out and talk to people. Sometimes we sell a lot of books, sometimes we don’t—but we always meet new people and do our best to turn them on to anarchist ideas.

TRAVELING OUTSIDE THE “ANARCHIST GHETTO”

And Rob really hit a nerve with “Both online and off, more effort has been put into looking at what the mainstream does, understanding why it works, and then turning out our own, more honest work.” I couldn’t agree more. Attending a sales conference at the Helmsley Hotel isn’t really my, um, cup of tea, but it helps get AK books into stores around the country and we learn new tips from our fellow publishers—anarchist or not. Everyday we’re on the phone with Ingram, drafting catalog copy for Consortium, making onesheets for the media, preparing new title updates to send out to our book trade contacts, sending Spring announcements to Publisher’s Weekly, and we’re tediously processing returns. Don’t know about Ingram, Consortium, or Publisher’s Weekly? Well, that’s because you are in the anarchist movement, and not the book trade.

What AK’s flurry of activity means—both as a publisher and distributor—is that anarchist ideas break out into the bookstores, the reviews journals, and get uploaded to Amazon, etc. When we handle distribution for publishers—like Freedom Press, Autonomedia, Black Cat, Bureau of Public Secrets, Charles H. Kerr, and the Kate Sharpley Library—they can rest well knowing that someone on our end is filling those purchase orders, warehousing the stock, and tracking down that money owed. It frees them up to what they do best: produce literature. But the scope of their reach will be determined in large part by how much effort they want to put into promoting their books. And believe me, it’s a lot of work.

What AK’s flurry of activity means—both as a publisher and distributor—is that anarchist ideas break out into the bookstores, the reviews journals, and get uploaded to Amazon, etc. When we handle distribution for publishers—like Freedom Press, Autonomedia, Black Cat, Bureau of Public Secrets, Charles H. Kerr, and the Kate Sharpley Library—they can rest well knowing that someone on our end is filling those purchase orders, warehousing the stock, and tracking down that money owed. It frees them up to what they do best: produce literature. But the scope of their reach will be determined in large part by how much effort they want to put into promoting their books. And believe me, it’s a lot of work.

CREATING AND MAINTAINING INFRASTRUCTURE

Over the years we’ve made our share of mistakes, but we’ve always tried to learn from them. And while publishing and distributing literature is not the only priority for the anarchist movement, it’s an integral part of laying the groundwork for making social and economic change attractive and coherent. So yes, we’re asking ourselves these same questions Rob poses and answering them from within and without “mainstream models.”

And I have an answer to Rob’s final comments: “What we don’t have, yet, is a central clearing house for all this information. We don’t have a database of potential outlets, or much in the way of guides to expected rates, the best approaches to take—how to close a distro deal. … Such an entity, or collective, creating and maintaining this kind of resource and with the ability to walk new groups through the minefield that is publishing, would be worth its weight in gold. As a creed that is supposed to excel in mutal aid, we desperately need something along these lines, and it’s a great shame that now, when we really need it, we haven’t got it.” Yes we do. AK is happy to be a helpful resource. And, possibly more importantly, there’s always the growing web of infoshops and radical/anarchist bookstores popping up around the US. There’s a healthy diversity in the style and approach these spaces take and, among the valuable services they offer their local communities, they can function as an alternative book trade. Tap into the Infoshop Network and find out more.

FROM PUBLISHING TO PRESENCE

To publish literally means “to make public.” We promote our ideas and histories but is it an end goal just to make books available? Do we measure “success” by our Amazon ranking? Certainly not. We need to reach people but let’s not let that pursuit become a substitute for action and efforts that can positively affect people’s daily lives (hopefully inspiring their own self-activity). In order to have a presence in society, we need to make public more than just new publications. We actually need to change the world. Let’s not lose sight of that.

You got specific questions about navigating the publishing world? Send them to blog@akpress.org or post them in the comments and we’ll try to answer them. With enough interest and a specific idea of what people would find most useful, perhaps we could do some “Distribution 101” posts.

Posted on April 15th, 2009 in AK Authors!, Happenings, Reviews

Diego Camacho, best known as Abel Paz, died on Monday, April 13, 2009 in Barcelona. What follows is a translation of a note announcing the sad news by Manel Aisa, Diego’s good friend and the pillar of the Ateneu Encyclopedic Popular Barcelona.

* * *

Diego Camacho / “Abel Paz” left us at 4:00 in the afternoon today, an eighty-seven year old anarchist who was born in Almería on August 12, 1921.

Diego Camacho / “Abel Paz” left us at 4:00 in the afternoon today, an eighty-seven year old anarchist who was born in Almería on August 12, 1921.

Diego witnessed many of the social struggles of the 20th century, including the eruption of the Spanish Revolution in Barcelona in 1936, during which he actively participated in the social changes of the times, creating the “Quixotes of the Ideal” group with his Libertarian Youth comrades from the Clot neighborhood.

When Spain’s war was over, he became familiar with the concentration camps in southern France and, under the Nazis, toiled as a slave laborer near Bordeaux during the Second World War.

But his commitment to freedom in Spain led him to return secretly to the country in the early 1940s. He was detained by Franco’s police and spent many years in Spanish prisons.

After completing his biography of Buenaventura Durruti, and autobiographical books documenting the many compelling moments of Spanish anarchism that he had experienced personally, he dedicated himself to disseminating his books through constant lectures in which he discussed the achievements of the Revolution.

He will be buried at 4:00pm on April 15 in Barcelona’s Sancho de Avila morgue.

Hasta siempre compañero.

[Translation by Chuck Morse]

Posted on April 14th, 2009 in AK Allies, Current Events

Franklin Rosemont, celebrated poet, artist, historian, street speaker, and surrealist activist, died Sunday, April 12 in Chicago. He was 65 years old. With his partner and comrade, Penelope Rosemont, and lifelong friend Paul Garon, he co-founded the Chicago Surrealist Group in 1966, an enduring and adventuresome collection of characters that would make the city a center for the reemergence of that movement of artistic and political revolt. Over the course of the following four decades, Franklin and his Chicago comrades produced a body of work, of declarations, manifestos, poetry, collage, hidden histories, and other interventions that has, without doubt, inspired an entirely new generation of revolution in the service of the marvelous.

Franklin Rosemont, celebrated poet, artist, historian, street speaker, and surrealist activist, died Sunday, April 12 in Chicago. He was 65 years old. With his partner and comrade, Penelope Rosemont, and lifelong friend Paul Garon, he co-founded the Chicago Surrealist Group in 1966, an enduring and adventuresome collection of characters that would make the city a center for the reemergence of that movement of artistic and political revolt. Over the course of the following four decades, Franklin and his Chicago comrades produced a body of work, of declarations, manifestos, poetry, collage, hidden histories, and other interventions that has, without doubt, inspired an entirely new generation of revolution in the service of the marvelous.

Franklin Rosemont was born in Chicago on October 2, 1943 to two of the area’s more significant rank-and-file labor activists, the printer Henry Rosemont and the jazz musician Sally Rosemont. Dropping out of Maywood schools after his third year of high school (and instead spending countless hours in the Art Institute of Chicago’s library learning about surrealism), he managed nonetheless to enter Roosevelt University in 1962. Already radicalized through family tradition, and his own investigation of political comics, the Freedom Rides, and the Cuban Revolution, Franklin was immediately drawn into the stormy student movement at Roosevelt.

Looking back on those days, Franklin would tell anyone who asked that he had “majored in St. Clair Drake” at Roosevelt. Under the mentorship of the great African American scholar, he began to explore much wider worlds of the urban experience, of racial politics, and of historical scholarship—all concerns that would remain central for him throughout the rest of his life. He also continued his investigations into surrealism, and soon, with Penelope, he traveled to Paris in the winter of 1965 where he found André Breton and the remaining members of the Paris Surrealist Group. The Parisians were just as taken with the young Americans as Franklin and Penelope were with them, as it turned out, and their encounter that summer was a turning point in the lives of both Rosemonts. With the support of the Paris group, they returned to the United States later that year and founded America’s first and most enduring indigenous surrealist group, characterized by close study and passionate activity and dedicated equally to artistic production and political organizing. When Breton died in 1966, Franklin worked with André’s wife, Elisa, to put together the first collection of Breton’s writings in English.

Active in the 1960s with the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), the Rebel Worker group, the Solidarity Bookshop and Students for a Democratic Society, Franklin helped to lead an IWW strike of blueberry pickers in Michigan in 1964, and put his considerable talents as a propagandist and pamphleteer to work producing posters, flyers, newspapers, and broadsheets on the SDS printing press. A long and fruitful collaboration with Paul Buhle began in 1970 with a special surrealist issue of Radical America. Lavish, funny, and barbed issues of Arsenal/Surrealist Subversion and special issues of Cultural Correspondence were to follow.

The smashing success of the 1968 World Surrealist Exhibition at Gallery Bugs Bunny in Chicago announced the ability of the American group to make a huge cultural impact without ceasing to be critics of the frozen mainstreams of art and politics. The Rosemonts soon became leading figures in the reorganization of the nation’s oldest labor press, Charles H. Kerr Company. Under the mantle of the Kerr Company and its surrealist imprint Black Swan Editions, Franklin edited and printed the work of some of the most important figures in the development of the political left: C.L.R. James, Marty Glaberman, Benjamin Péret and Jacques Vaché, T-Bone Slim, Mother Jones, Lucy Parsons, and, in a new book released just days before Franklin’s death, Carl Sandburg. In later years, he created and edited the Surrealist Histories series at the University of Texas Press, in addition to continuing his work with Kerr Co. and Black Swan.

A friend and valued colleague of such figures as Studs Terkel, Mary Low, the poets Philip Lamantia, Diane di Prima, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, and Dennis Brutus, the painter Lenora Carrington, and the historians Paul Buhle, David Roediger, John Bracey, and Robin D.G. Kelley, Rosemont’s own artistic and creative work was almost impossibly varied in inspirations and results. Without ever holding a university post, he wrote or edited more than a score of books while acting as a great resource for a host of other writers.

He became perhaps the most productive scholar of labor and the left in the United States. His spectacular study, Joe Hill: The I.W.W. and the Making of a Revolutionary Workingclass Counterculture, began as a slim projected volume of that revolutionary martyr’s rediscovered cartoons and grew to giant volume providing our best guide to what the early twentieth century radical movement was like and what radical history might do. His coedited volume Haymarket Scrapbook stands as the most beautifully illustrated labor history publication of the recent past. Indispensable compendiums like The Big Red Songbook, What is Surrealism?, Menagerie in Revolt, and the forthcoming Black Surrealism are there to ensure that the legacy of the movements that inspired him continue to inspire young radicals for generations to come. In none of this did Rosemont separate scholarship from art, or art from revolt. His books of poetry include Morning of a Machine Gun, Lamps Hurled at the Stunning Algebra of Ants, The Apple of the Automatic Zebra’s Eye and Penelope. His marvelous fierce, whimsical and funny artwork—to which he contributed a new piece every day—graced countless surrealist publications and exhibitions.

Indeed, between the history he himself helped create and the history he helped uncover, Franklin was never without a story to tell or a book to write—about the IWW, SDS, Hobohemia in Chicago, the Rebel Worker, about the past 100 years or so of radical publishing in the US, or about the international network of Surrealists who seemed to always be passing through the Rosemonts’ Rogers Park home. As engaged with and excited by new surrealist and radical endeavors as he was with historical ones, Franklin was always at work responding to queries from a new generation of radicals and surrealists, and was a generous and rigorous interlocutor. In every new project, every revolt against misery, with which he came into contact, Franklin recognized the glimmers of the free and unfettered imagination, and lent his own boundless creativity to each and every struggle around him, inspiring, sustaining, and teaching the next generation of surrealists worldwide.

Posted on April 13th, 2009 in AK Authors!, Happenings

We know you’re all anxiously awaiting the appearance of Josh MacPhee and Dara Greenwald’s incredible new compendium of movement art, Signs of Change (due out later this season). Hopefully some of you had the chance to catch the actual gallery show when it graced the walls of NYC’s Exit Art or Pittsburgh’s Miller Gallery last year, but if not, you have another chance: Signs of Change has just begun a new engagement at The Arts Center of the Capital Region in Troy, NY, and runs until June 5!

Check out the description for the show, and photos from the install below (courtesy of the JustSeeds blog).

**********

Signs of Change: Social Movement Cultures 1960s to Now

Reception: April 24, 2009 5:00-9:00 PM

Exhibition runs from April 5, 2009 – June 5, 2009

The Arts Center of the Capital Region, 265 River Street, Troy NY, 518.273.0552,

Sponsored by iEAR Presents! and Humanities at Rensselaer

In Signs of Change: Social Movement Cultures 1960s to Now, hundreds of posters, photographs, moving images, audio clips, and ephemera bring to life over forty years of activism, political protest, and campaigns for social justice. Curated by Dara Greenwald and Josh MacPhee as part of Exit Art’s Curatorial Incubator, this important and timely exhibition surveys the creative work of dozens of international social movements.

Organized thematically, the exhibition presents the creative outpourings of social movements, such as those for Civil Rights and Black Power in the United States; democracy in China; anti-apartheid in Africa; squatting in Europe; environmental activism and women’s rights internationally; and the global AIDS crisis, as well as uprisings and protests, such as those for indigenous control of lands; against airport construction in Japan; and student and worker revolution in France. The exhibition also explores the development of powerful counter-cultures that evolve beyond traditional politics and create distinct aesthetics, life-styles, and social organization.

Although histories of political groups and counter-cultures have been written, and political and activist shows have been held, this exhibition is a groundbreaking attempt to chronicle the artistic and cultural production of these movements. Signs of Change offers a chance to see relatively unknown or rarely seen works, and is intended to not only provide a historical framework for contemporary activism, but also to serve as an inspiration for the present and the future.

|

|

Posted on April 10th, 2009 in About AK, AK Allies

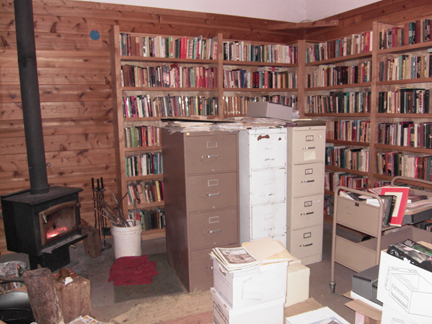

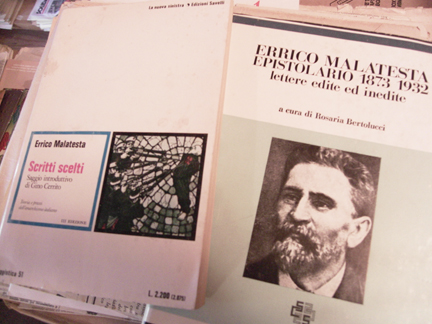

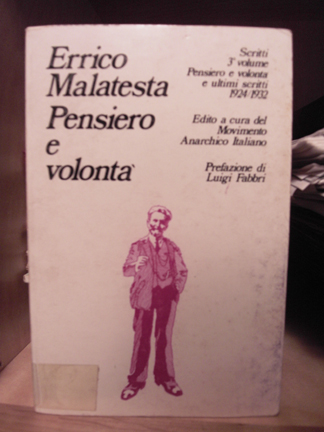

Zach and I have taken a two day “working vacation” to head up to the Kate Sharpley Library in Grass Valley, CA. Our ostensible reason is to do research for an upcoming Malatesta Reader that AK Press is planning to publish: digging up harder-to-find works, as well as any material we can find in Italian that has yet to be translated (a task that’s somewhat impeded by the fact that neither of us actually read Italian. In effect, we’re flagging pieces for Paul Sharkey to look at.).

Of course, once one enters the KSL archives, distractions, tangents, and circuitous meanderings are inevitable. It’s impossible to take two steps in any direction without finding some fascinating nugget to absorb your attention, and inspire yet another publishing idea. The danger is compounded by the fact that KSLers Barry Pateman and John Patten (who’s in town from the UK for a couple of weeks) are on hand to stoke the fires of welcome distraction.

The “vacation” part of the working vacation is the idyllic setting, leisurely reading, Barry’s chili, good conversation (ranging from the state of contemporary anarchism to the musical legacy of Dusty Springfield), and, for me at least, cracking your first beer in the early afternoon…even as you type up your Friday blog post.

Thanks to Barry and John for a swell time and, for those of you who’ve never made the trip to Grass Valley, here are some photos:

Posted on April 8th, 2009 in Happenings

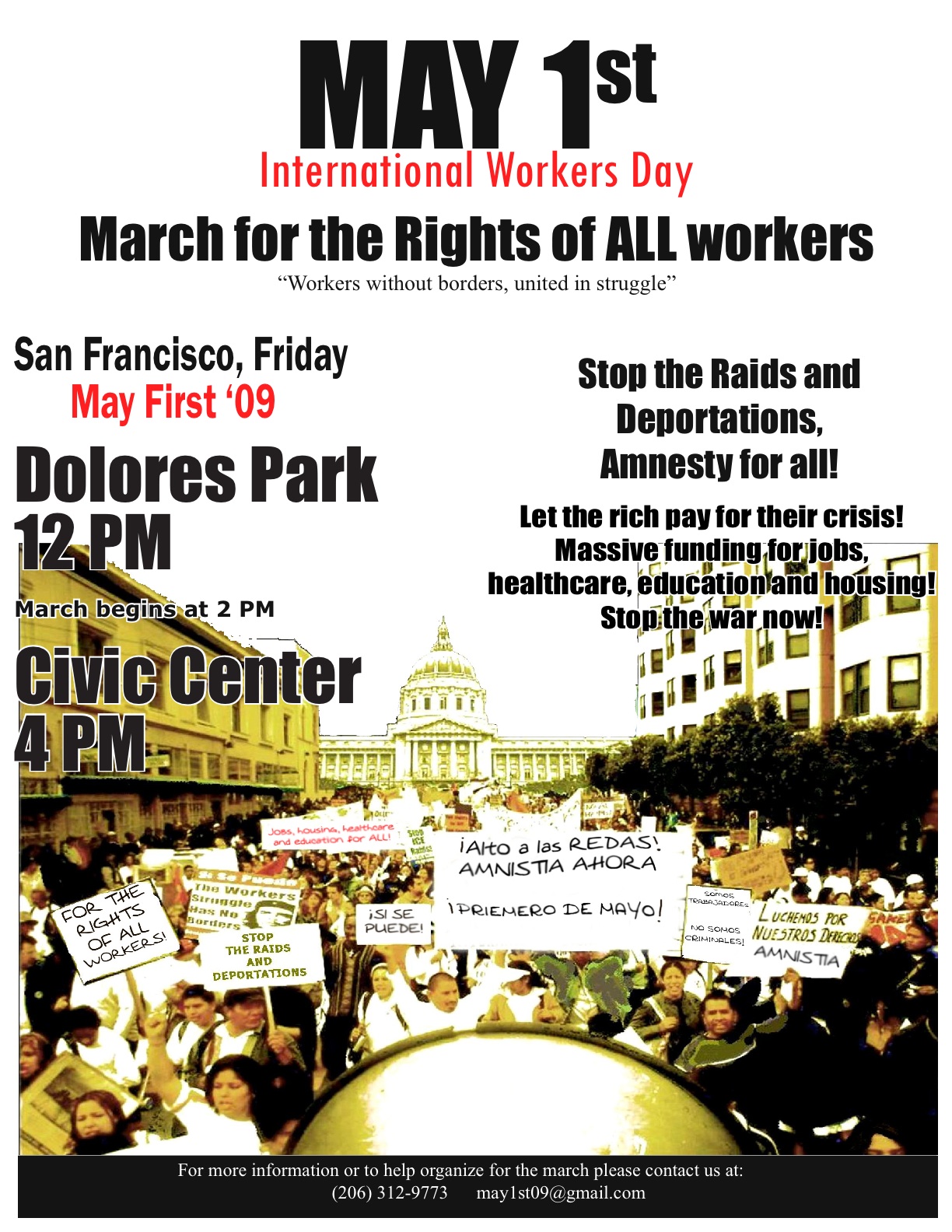

Mayday is a very important event in the history of anarchism and will be celebrated in many different ways in the Bay Area (and worldwide)

this year. We will do our best to keep you informed about significant

attempts to mark the date.

The following flyer announces a rally organized—we think—by the Peace and Freedom Party, who are not anarchists by any stretch of the imagination, but probably won’t try to browbeat you

into joining the party either.

Posted on April 6th, 2009 in AK Allies

Being the compulsive nerd that I am, I’ve set up a bunch of Google Alerts to inform me when any mention of anarchism (or related terms) show up on the almighty web. Every day, the Google mothership sends me two to four emails, each with links to anywhere from two to a dozen news or blog posts. And, in each email, there’s usually one or two links worth checking out. This, of course, leads to an hour or so of screen-reading and link-hopping.

It’s always amazing to me how much interesting stuff is out there (and, of course, how much utter crap), though I sometimes despair of making sense of it all, let alone obsessively organizing my browser’s bookmarks in order to be able to find any of it again.

During today’s electronic meandering, I wound up at a site that I really should have mentioned on this blog long ago: The Anarchist Studies Network…especially since I’m a member of their useful and thought provoking listserv. We did provide a link to it in the interview Zach did with Dave Berry last August, but I thought they deserved a more explicit call-out. So…

The Anarchist Studies Network is an academically oriented group. More specifically, it is an official Specialist Group of the Political Studies Association (UK), whose principal aims are to coordinate and promote the re-investigation of anarchism as a political ideology. Currently headed by Ruth Kinna, Alex Pritchard, and Dave Berry, they organize conferences, foster research and discussion, and, I think, add a lot to anarchist theory by defining “anarchist studies” not simply as the study of anarchism, but as the study of the world from an anarchist standpoint.

(more…)

Posted on April 4th, 2009 in Current Events

Archie Green, 1917–2009

by Nathan Salsburg

Published in the April 1 edition of the Louisville Eccentric Weekly (LEO).

Archie Green at home. Courtesy of Adam Machado

In mid-December, Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi received a memorandum from a constituent on Caselli Street in San Francisco. President-Elect Obama had been publicly ginning up support for the stimulus package he would submit to Capitol Hill immediately after his inauguration, and the constituent, 91-year-old Archie Green, had a bit of historical perspective to share with Madame Speaker. He reminded Pelosi that during the New Deal there weren’t just roads paved and bridges built; federal agencies stimulated all manner of American ingenuity and creativity, and reflected the best parts of the country back to itself.

“The Federal Writers Project,” Green wrote, “included a folk unit that both preserved and presented workers’ culture” through photography, recordings, film, and journalism, and he advocated the establishment of a similar cultural unit to document the occupational experience of the current stimulus projects.

Green, who died March 22, was a shipwright, union activist, labor historian, folklorist, record collector, professor, author, a wholly unreconstructed progressive, and the progenitor of the theory and expert of the practice of “laborlore.” Defined as the expressive culture—song, story, slang, and technical know-how—of workers, laborlore blew open the hermetically sealed pantheon of generalized American “folk” archetypes—the Yankee, the Negro, the Indian, the hillbilly, the lumberjack, the cowboy—all of which had long prevailed in both popular and academic consciousnesses. Archie insisted on a deeper, more fluid understanding of American diversity, reflected by the diversity of occupational involvement, and to be seen where any two bodies gather to work a job together, swapping stories, jokes, and expertise. Ingredients of class solidarity and union brotherhood, to be sure, but also, and more essentially, a proud, conscious, and engaged citizenry.

(more…)

Posted on April 1st, 2009 in About AK, AK Distribution, AK News

Greetings! In addition to publishing great literature AK Press also distributes amazing and often hard to find books. AK Press stands as the exclusive distributor for many publishers, including Microcosm, Autonomedia, Arbeiter Ring, and Charles H. Kerr. Now, AK Press Distribution brings to you a selection of our latest releases. Once a month AK Distro will list our top ten new and most exciting items. Be sure to check out the new titles! For more information and frequent updates please join our mailing list.

10. Queen of the Bolsheviks: The Hidden History of Dr. Marie Equi Now forgotten, Dr. Marie Equi was a physician for working-class women and children, a lesbian, and a dynamic and flamboyant political activist. Equi’s life serves as a chronicle of her times and illuminates how one person was affected by and sought to change world events. 10. Queen of the Bolsheviks: The Hidden History of Dr. Marie Equi Now forgotten, Dr. Marie Equi was a physician for working-class women and children, a lesbian, and a dynamic and flamboyant political activist. Equi’s life serves as a chronicle of her times and illuminates how one person was affected by and sought to change world events. |

|

9. The Anarchist’s Book of Verse This book of Brian Gianelli’s and poetry is published in tribute to his life and his ideals. Sales of the book go toward providing scholarships for students in all disciplines of art. 9. The Anarchist’s Book of Verse This book of Brian Gianelli’s and poetry is published in tribute to his life and his ideals. Sales of the book go toward providing scholarships for students in all disciplines of art. |

|

8. Black Women: Bringing It All Back Home From Barbados to Brooklyn, from Jamaica to England, two accounts of girlhood in the Caribbean, the upheaval of leaving and the conflicts of being an immigrant. 8. Black Women: Bringing It All Back Home From Barbados to Brooklyn, from Jamaica to England, two accounts of girlhood in the Caribbean, the upheaval of leaving and the conflicts of being an immigrant. |

|

7. The Red Army Faction, A Documentary History: Vol 1, Projectiles for the People Through its bombs and manifestos the RAF confronted the state with opposition at a level many activists today might find difficult to imagine. 7. The Red Army Faction, A Documentary History: Vol 1, Projectiles for the People Through its bombs and manifestos the RAF confronted the state with opposition at a level many activists today might find difficult to imagine. |

|

|

6. It’s Our Time: Ella Baker, Participatory Democracy, & Oakland, California The insights in this book are designed to provide a new generation of activists with the background needed to overcome the challenges we face and chart a path to a better future. 6. It’s Our Time: Ella Baker, Participatory Democracy, & Oakland, California The insights in this book are designed to provide a new generation of activists with the background needed to overcome the challenges we face and chart a path to a better future.

|

|

|

5. Resistance Behind Bars: The Struggles of Incarcerated Women In 1974, women imprisoned at New York’s maximum-security prison at Bedford Hills staged what is known as the August Rebellion. Protesting the brutal beating of a fellow prisoner, the women fought off guards, holding seven of them hostage, and took over sections of the prison. 5. Resistance Behind Bars: The Struggles of Incarcerated Women In 1974, women imprisoned at New York’s maximum-security prison at Bedford Hills staged what is known as the August Rebellion. Protesting the brutal beating of a fellow prisoner, the women fought off guards, holding seven of them hostage, and took over sections of the prison.

|

|

|

4. Animal Rights: A Very Short Introduction David DeGrazia explores the implications for how we treat animals in connection with our diet, zoos, and research. 4. Animal Rights: A Very Short Introduction David DeGrazia explores the implications for how we treat animals in connection with our diet, zoos, and research.

|

|

|

3. Arena: On Anarchist Cinema Arena aims to tap into the end of the Cold War and worldwide protests against corporate globalization, anarchism continues to attract new adherents among both aging leftists and new generations of young radicals. 3. Arena: On Anarchist Cinema Arena aims to tap into the end of the Cold War and worldwide protests against corporate globalization, anarchism continues to attract new adherents among both aging leftists and new generations of young radicals.

|

|

|

2. Down But Not Out/Dos Americas: the Reconstruction of New Orleans Providing accounts of living in a city whose populace has largely been forgotten, the survivors give a stinging description of a slow reconstruction process that is ignoring the human cost of rebuilding. But Not Out shows the people directly affected by the fallout from Hurricane Katrina, and lets those who experienced it tell the stories themselves. 2. Down But Not Out/Dos Americas: the Reconstruction of New Orleans Providing accounts of living in a city whose populace has largely been forgotten, the survivors give a stinging description of a slow reconstruction process that is ignoring the human cost of rebuilding. But Not Out shows the people directly affected by the fallout from Hurricane Katrina, and lets those who experienced it tell the stories themselves.

|

|

|

1. Women, the Unions and Work or…What is Not to be Done and the Perspective of Winning With this pamphlet feminism finally broke out of the political ghetto which confined “women’s issues” to a no-man’s-land outside of class. ALSO AVAILABLE: The Rapist Who Pays the Rent: Women’s Cast for Changing the Law on Rape and Black Women and the Peace Movement. 1. Women, the Unions and Work or…What is Not to be Done and the Perspective of Winning With this pamphlet feminism finally broke out of the political ghetto which confined “women’s issues” to a no-man’s-land outside of class. ALSO AVAILABLE: The Rapist Who Pays the Rent: Women’s Cast for Changing the Law on Rape and Black Women and the Peace Movement.

|

|

|

|

Posted on March 30th, 2009 in Reviews of AK Books

Roots of My Radicalism: A Review of Granny Made Me an Anarchist

Eleanor J. Bader From the March 20, 2009 issue of the Indypendent

Granny Made Me an Anarchist: General Franco, the Angry Brigade and Me By Stuart Christie AK Press, 2007

Growing up, many of us got from Granny what we didn’t get from Mom or Dad: attention, indulgence and wisdom, the stuff that molds identity and prepares us for the world. Scottish anarchist Stuart Christie describes his grandmother as his “strongest moral influence.” Independent, hard-working, generous and smart, she taught him to stand up for his beliefs and take the consequences.

And he has. As he recounts in Granny Made Me an Anarchist, his grandmother began teaching him right from wrong shortly after his 1946 birth, from tolerance toward Catholics to hatred for authoritarian rule. As a teenager he began reading political tracts and became incensed that Generalissimo Franco had retained his title as head of Spain’s government. Inspired by thousands of antifascists who joined the International Brigades of the 1930s, Christie became obsessed. “I simply could not understand why the Allies permitted Franco to remain in power after 1945,” he writes.

The question burned until Christie, determined to do something about what he saw as worldwide acquiescence to the dictator, found a group of like-minded youth. A plan was developed — direct action to show the world that “some people were still fighting the Franco regime.” Barely 18 and speaking no Spanish, Christie traveled to Madrid with explosives taped to his body. The scheme involved picking up a directive and then delivering the weapons to a saboteur. Not surprisingly, things went awry. “As I steeled myself to make a dash through the crowds, I was suddenly grabbed by both arms from behind, the anorak ripped from me, my face pushed to the wall and a gun barrel thrust into the small of my back… It was over in a matter of minutes,” he recalls.

In short order, Christie was charged with banditry and terrorism, death penalty offenses. The media ran sensationalist story after sensationalist story about the “kilted assassin.” A trial led to a guilty verdict and a two-decade sentence was imposed. Interestingly, while the memoir dubs the incident an act of adolescent rebellion, Christie neither condemns his youthful ardor nor denies the need to fight oppression by force. At the same time, he never romanticizes violence, knowingly presenting the psychological toll caused by hurting another person.

Christie served just three years of his punishment. Upon his release in 1967 he found that the world had exploded. His head spun as he learned of Israel’s six-day attack on Egypt and Syria; anti-Shah demonstrations in Iran; marches against the Vietnam war in the United States; and the death of Che Guevara. His response? Continued political engagement.

Attacks throughout the U.K., carried out by groups like the Angry Brigade, put Christie on police radar and his every move was monitored. The 1968 bombing of the homes of two British officials upped the ante and a dragnet eventually rounded up eight anarchists, including Christie. A yearlong trial ultimately freed him, but imprisoned several of his comrades.

It’s a gripping story, told with humor and passion. Unfortunately, the book ends with Christie’s 1975 acquittal and offers few clues about his next three decades as a writer and activist. That aside, Christie has crafted an engrossing—if occasionally communist-bashing—political thriller. Like all good memoirs, his story is emotional, fast-paced and moving. Better yet, its adherence to grandma’s moral stance resonates. As she said, “We are not bystanders to life.” Christie’s actions may not be your cup of tea, but his passion is exhilarating.

* * *

April 1 is the 70th anniversary of the end of the Spanish Civil War, where General Francisco Franco founded his right-wing dictatorship.

I’m not sure that the quality of anarchist publications has improved overall (design and readability is improving, editing and fact-checking are going in the right direction but we have a long way to go still). And I think sales have increased (again, for some, not others, but largely due to making publications available through mainstream channels). But I agree that it is always crucial for anarchist publishers to find better ways to distribute their materials and that it’s a great idea for us to share, and find new, resources to help everyone reach a wider readership. Cover design alone doesn’t move books, but some knowledge and experience about what does move them exists—there’s no need to reinvent the wheel. AK Press has been operating for almost two decades now under an assumption that anarchist ideas are not only worthy of being “in the mainstream,” but had better find a sizable following there (or else, um, there’s little hope in working toward an anarchist future).

I’m not sure that the quality of anarchist publications has improved overall (design and readability is improving, editing and fact-checking are going in the right direction but we have a long way to go still). And I think sales have increased (again, for some, not others, but largely due to making publications available through mainstream channels). But I agree that it is always crucial for anarchist publishers to find better ways to distribute their materials and that it’s a great idea for us to share, and find new, resources to help everyone reach a wider readership. Cover design alone doesn’t move books, but some knowledge and experience about what does move them exists—there’s no need to reinvent the wheel. AK Press has been operating for almost two decades now under an assumption that anarchist ideas are not only worthy of being “in the mainstream,” but had better find a sizable following there (or else, um, there’s little hope in working toward an anarchist future). lishers] are having difficulty finding new places to stock [books, magazines] and hawk them around.” No doubt this seems increasingly true, but the picture is much broader than one might expect. The obvious place to start selling books is through the book trade. The good news is that almost anyone will carry your books (from Amazon to Barnes & Noble to City Lights)—if they feel that someone will wander in and buy them. So, since City Lights is a great bookstore and readily stocks radical literature, the big question is: who is going to buy our books from Barnes & Noble and the like? Well, to be honest, lots of people. In my opinion, the challenge is how to convince the B&N buyers that your book is going to sell (and hence it’s worth them stocking it). Well, that’s the icky marketing and publicity side of things. You want to gain access to these places? There’s two ways to do it: have convincing-enough marketing and publicity plans in place or buy your way in—large stores have “programs” where you can basically rent space in the store. Book stores are a business. Buying shelf space doesn’t guarantee sales for the publisher but it guarantees income for the store (Amazon has similar programs in place to “promote” your book for a fee). Amazon is the fastest-growing bookseller, hands down. They extract non-negotiable fees from AK’s main distributor (that we end up having to pay ourselves) just to sell through them. Wholesale distributors have similar plans in place to extract money from publishers and smaller distributors (in the form of warehousing fees, catalog fees, fees on books returned, etc.). It’s called business. You don’t like it? Neither do we, but that’s the playing field.

lishers] are having difficulty finding new places to stock [books, magazines] and hawk them around.” No doubt this seems increasingly true, but the picture is much broader than one might expect. The obvious place to start selling books is through the book trade. The good news is that almost anyone will carry your books (from Amazon to Barnes & Noble to City Lights)—if they feel that someone will wander in and buy them. So, since City Lights is a great bookstore and readily stocks radical literature, the big question is: who is going to buy our books from Barnes & Noble and the like? Well, to be honest, lots of people. In my opinion, the challenge is how to convince the B&N buyers that your book is going to sell (and hence it’s worth them stocking it). Well, that’s the icky marketing and publicity side of things. You want to gain access to these places? There’s two ways to do it: have convincing-enough marketing and publicity plans in place or buy your way in—large stores have “programs” where you can basically rent space in the store. Book stores are a business. Buying shelf space doesn’t guarantee sales for the publisher but it guarantees income for the store (Amazon has similar programs in place to “promote” your book for a fee). Amazon is the fastest-growing bookseller, hands down. They extract non-negotiable fees from AK’s main distributor (that we end up having to pay ourselves) just to sell through them. Wholesale distributors have similar plans in place to extract money from publishers and smaller distributors (in the form of warehousing fees, catalog fees, fees on books returned, etc.). It’s called business. You don’t like it? Neither do we, but that’s the playing field. folks who never set foot into a bookstore and don’t troll Amazon for new books? AK Press reaches them by tabling at a variety of events, networking with other groups, and passing out catalogs. Certainly we endeavor to attend as many radical events as possible (see our Spring list here) but we also get out to places where our literature isn’t commonplace. Whether it’s the Barrio Bookfest in LA, the Sonoma County Book Festival, the Baltimore Book Festival, the San Diego International Book Festival, or The Crossroads of the West Gun Show (yes, two of us tabled there a few years back), we actually go out and talk to people. Sometimes we sell a lot of books, sometimes we don’t—but we always meet new people and do our best to turn them on to anarchist ideas.

folks who never set foot into a bookstore and don’t troll Amazon for new books? AK Press reaches them by tabling at a variety of events, networking with other groups, and passing out catalogs. Certainly we endeavor to attend as many radical events as possible (see our Spring list here) but we also get out to places where our literature isn’t commonplace. Whether it’s the Barrio Bookfest in LA, the Sonoma County Book Festival, the Baltimore Book Festival, the San Diego International Book Festival, or The Crossroads of the West Gun Show (yes, two of us tabled there a few years back), we actually go out and talk to people. Sometimes we sell a lot of books, sometimes we don’t—but we always meet new people and do our best to turn them on to anarchist ideas.

Franklin Rosemont, celebrated poet, artist, historian, street speaker, and surrealist activist, died Sunday, April 12 in Chicago. He was 65 years old. With his partner and comrade, Penelope Rosemont, and lifelong friend Paul Garon, he co-founded the

Franklin Rosemont, celebrated poet, artist, historian, street speaker, and surrealist activist, died Sunday, April 12 in Chicago. He was 65 years old. With his partner and comrade, Penelope Rosemont, and lifelong friend Paul Garon, he co-founded the