1st Libertarian Encounter: Anarchism & Social Movements (in Fortaleza, Brazil)

From 8-11 December 2008, the Organização Resistência Libertária (ORL – Libertarian Resistance Organization) will be hosting the 1st Libertarian Encounter in Fortaleza (north-eastern Brazil). The event will see the participation of members of anarchist political organizations from various Brazilian cities, militants from the social movements, sympathisers, and the curious. Through this initiative, we hope to create a space for exchanging experiences and methodologies between people who are involved in developing ideas and concrete forms in the anti-capitalist struggle from a libertarian perspective.

There will be four days of workshops, debates, discussions, lectures, exhibitions, cultural activities, and informal meetings around themes such as social anarchism, libertarian education, independent media, homeless and housing movements, social ecology, the student movement, libertarian organization, ethnic resistance, the anti-capitalist struggle, and more.

We believe that the anti-capitalist struggle can only make important and long-lasting advances if its social roots and dimensions are continually widened. Therefore, we think that anarchism must be present inside the social struggles and at their service, encouraging autonomy, direct action, combativity, and direct democracy. This insertion must in no way seek to manage the struggles or submit them to particular interests, but instead contribute in such a way that they can go beyond their immediate demands and take on a libertarian, revolutionary nature seeking to overthrow capitalist society.

We invite everyone to participate in this occasion for meeting and getting to know each other, so that we can join forces and make longer, stronger steps towards developing and building opportunities for organization and struggle with an anti-capitalist, libertarian perspective.

The great are only great because we are on our knees! Rise up!!

* * *

For more information, see: http://encontrolibertario.blogspot.com/

Free E-Books from Traficantes de sueños

Spanish readers interested in radical theory and history will welcome the news that Madrid’s oppositional bookstore and publisher, Traficantes de sueños, has decided to make all of its publications available online for free in PDF format.

You can visit their entire catalog here.

Some notable titles (among many others) are:

| Con la comida no se juega. Alternativas autogestionarias a la globalización capitalista desde la agroecología y el consumo by Daniel López García and J. Ángel López López |  |

| Autogestión y anarcosindicalismo en la España revolucionaria by Frank Mintz |  |

| Las huelgas en Francia durante mayo y junio de 1968 by Bruno Astarian |  |

Free E-Book: Critical Geographies: A Collection of Readings

For a free, awesome, and huge (728 pages!) e-book on radical geography that emphasizes anarchism, check out Harald Bauder and Salvatore Engel-Di Mauro’s Critical Geographies: A Collection of Readings (Praxis (e) Press, 2008).

For a free, awesome, and huge (728 pages!) e-book on radical geography that emphasizes anarchism, check out Harald Bauder and Salvatore Engel-Di Mauro’s Critical Geographies: A Collection of Readings (Praxis (e) Press, 2008).

Introduction: Critical Scholarship, Practice and Education

Harald Bauder and Salvatore Engel-Di Mauro

Part I: Critical Reflections

What Geography Ought to Be

Peter Kropotkin (1885)

Introduction to a Critique of Urban Geography

Guy Debord (1955)

Activism and the Academy

Nicholas K. Blomley (1994)

Reinventing Radical Geography: Is All That’s Left Right?

Vera Chouinard (1994)

The International Critical Geography Group: Forbidden Optimism?

Smith and Caroline Desbiens (1999)

Reflections on a White Discipline

Laura Pulido (2002)

Learning to Become a Geographer: Reproduction and Transformation in Academia

Harald Bauder (2006)

Part II: Space & Society

(more…)

The Empire Is Losing Its Grip: An Interview with Joaquin Cienfuegos

Joaquin Cienfuegos, twenty-five, is a longtime anarchist militant, member of Revolutionary Autonomous Communities, Cop Watch Los Angeles, Anarchist People of Color (APOC), and one of the organizers of the first annual LA Anarchist Bookfair, which will occur on December 13, 2008. I spoke with Cienfuegos about his recent conflicts with law enforcement and his activism generally. ~ Chuck Morse

Communities, Cop Watch Los Angeles, Anarchist People of Color (APOC), and one of the organizers of the first annual LA Anarchist Bookfair, which will occur on December 13, 2008. I spoke with Cienfuegos about his recent conflicts with law enforcement and his activism generally. ~ Chuck Morse

* * *

Can you tell us about your arrest in July and where your case stands at the moment?

On June 27, the police pulled me over as I was giving a compañero a ride to his house. They looked through my trunk and found fliers for the Summer Solidarity Festival for the Black Rider 3 (three political prisoners held on trumped up conspiracy and weapons charges) and then pulled out a black case holding my legally owned AR-15. They immediately took me into custody and charged me with unlawful possession of an assault rifle.

This wasn’t the first time I’ve dealt with political repression or with police harassment. Growing up Chicano in the neo-colonies of Fresno and South Central, Los Angeles, this is business as usual. Of course, the state wants to have a monopoly on guns and violence and views everyone in our communities as criminals. That is why they relate to us in the way they do and don’t hesitate to kill innocent people in our neighborhoods.

I’m fighting my case. My next court date is November 6. Guillermo Suarez, a radical civil rights attorney, is representing me. And people in the movement generally, and anarchists around the world in particular, have supported me, my family, and my organization.

What can people do to support you?

Any support is appreciated. I was bailed out thanks to the help of the people, my friends and comrades, and we want to pay those folks back. We have a website up where people can contribute at www.diyzine.com/freejoaquin.

Also, the Revolutionary Autonomous Communities (RAC), along with Anarchist People of Color (APOC), is building a defense fund so we will be prepared when something like this happens again in the future. We know that this isn’t the first or last time that there will be political repression.

You’re active in a wide range of local activities. Please tell us about these.

I’ve been involved in Cop Watch LA for almost three years. We came out of the STOP Coalition (Stop Terrorism and Oppression by the Police), the Los Angeles Chapter of the Southern California Anarchist Federation (SCAF), the Raise the Fist Direct Action Network, and youth involved in defending the South Central Farm.

(more…)

Will you carry the torch? An interview with Ashanti Alston

The following phone interview with Ashanti Alston was conducted on 19 February 2006 by Dina Rodriguez and myself. It was originally published in The Matrix Magazine—a student-run publication out of Humboldt State University’s Women’s Resource Center. Dina and I met Ashanti while undergrads at HSU. Acción Zapatista de Humboldt, the Black Student Union, and other local groups had organized to bring Ashanti to Humboldt as part of his larger west coast speaking tour. At the time of his first visit to Humboldt, we had no idea that Ashanti would become such a prominent and inspiring figure in our lives, in terms of both our political and intellectual development.

The following phone interview with Ashanti Alston was conducted on 19 February 2006 by Dina Rodriguez and myself. It was originally published in The Matrix Magazine—a student-run publication out of Humboldt State University’s Women’s Resource Center. Dina and I met Ashanti while undergrads at HSU. Acción Zapatista de Humboldt, the Black Student Union, and other local groups had organized to bring Ashanti to Humboldt as part of his larger west coast speaking tour. At the time of his first visit to Humboldt, we had no idea that Ashanti would become such a prominent and inspiring figure in our lives, in terms of both our political and intellectual development.

For those of you who do not know, Ashanti Alston is a former political prisoner who was part of the Black Panther Party and the Black Liberation Army. Referring to his prison cell as his “university,” Ashanti emerged from that cell to become one of the most sought after anarchist lecturers/speakers in the US. I think the reason that so many of us are drawn to Ashanti is the fact that he is able to connect various struggles—from the Zapatista movement, to anarchism, to prison abolition, to queer liberation, to radical feminism, to people of color struggles, to earth liberation—with a critical eye, engaging language, and a great deal of humility. You can see these aspects of his personality shine through even in his business cards, where his qualifications are listed as: Revolutionary Trickster, Anarchist of African Descent, Wannabe Diehard Elder.

Since his first visit to Humboldt, Ashanti has been invited back up too many times to even keep count. See below for a partial glimpse of why he has a rolling invite to our community.

– Victoria Gutierrez

(Note: please keep in mind that this was a recorded telephone conversation and was transcribed as such—a conversation. This might explain why the flow is a bit choppy at times and a bit hard to understand at others. Enjoy!)

* * *

Matrix: Can you tell us a little bit about your work?

A.A.: Of course, you know Estación Libre (EL)—that’s probably my main organization. Right here in the New York chapter, we just had a delegation back from Chiapas—so a lot of it is setting up little report-backs for them. And then also just gathering up that energy to come back with and do everything from fundraisers to political education stuff. So that’s my main thing here.

Also, I’m a member of Critical Resistance. Our thing here is, we have an upcoming round table—this is the second round table. And it’s all part of this idea of establishing, [of] helping groups in particular communities develop a “harm-free zone”—and a harm free zone is the idea of getting people away from dialing 911, dialing the police every time there’s a problem. But it’s, like, being able to offer the different communities ways that that can happen. For example, if we need conflict resolution or mediation skills, can we offer that kind of training to communities who want to do this? Are there intervention skills? Like if there’s some direct violence in the street; whether it involves street organizations of the criminal activity or maybe just domestic violence—can we find ways of intervening?

And it’s not for us as Critical Resistance to intervene. We want to identify folks in communities who are willing to do this kind of work—and we will help to provide the trainings and the resources to make it happen. We had one round table discussion about three months ago; this is the second one that’s coming up. So there’s follow-up work around that from the organizations that came to the first one, and then preparing for this second one—but also we’re always identifying folks who can provide training or resources to make this happen.

Other than that I do political prisoner work—but I’m not doing that with a particular organization; though I work closely with people from the Jericho movement. I guess the last year I’ve been back into visiting the political prisoners in New York state more. And right now I’m just trying to talk to folks from different organizations who have not worked together—for all kinds of political and personal reasons—to see if I can encourage them to sit down at the table and work out some agreements, principles, that would allow them to work—even as different organizations and not let differences from the past stop them.

I don’t get to do this much—but the Institute for Anarchist Studies (IAS)…Lately I’ve been on a little speaking thing, I get more speaking engagements, and it hasn’t been possible for me to do more [with IAS]. But when I can, I do participate in that, even if it’s doing a speaking engagement that would help to raise money for the Institute.

Matrix: Speaking of anarchism—you self-identify as an anarchist, right? We were wondering what were some of the key elements of anarchism that draw you to that political philosophy.

A.A: For me anarchism showed me some weaknesses in a Marxist-Leninist or Maoist approach, which is what I came out of, being a member of the Black Panther Party (BPP). And specifically around internalized oppression, [and the] internal structure of the organization; in terms of the organization being structured on a hierarchical basis, and the whole authoritarian thinking and ideology that comes with that…Also I think what attracted me to anarchism was that it was giving me a better understanding of diversity, and like what the Zapatistas say…the vision of creating a world where many worlds fit. That, I was getting more from an anarchist perspective, because all of them [anarchists] were helping me to reflect on my past and the BPP, to see some serious errors we made.

(more…)

No Foe Too Large: Lucio Uturbia’s Fight for Freedom

Lucio is a documentary film about the life and work of an anarchist militant, Lucio Uturbia, a hard-working bricklayer of Spanish peasant stock. For over thirty years, when his workday was done, Lucio spearheaded forgery campaigns that funded clandestine activity the world over. His counterfeited Travelers’ Checks that cost City Bank an estimated $15 million, coupled with his fake passports, lent direct support to the anti-Franco resistance and a host of other groups, such as the Red Brigades, the Baader-Meinhof Gang, the Black Panthers, and the Tupac Amarus, among others.

Lucio was born in 1931, in the town of Cascante. As a rebellious teenager, he took part in a smuggling operation across the French border, for which he was eventually arrested. He later entered the military where, up to his old tricks, he smuggled army supplies out of the barracks and sent them to his family for resale. This came to an end when, after learning that his co-conspirators had been caught red-handed, Lucio made his way to Paris, where he became a bricklayer and tiler. He was a hard worker and militant supporter of the local union movement. When asked by CNT laborers about his political affiliations, he answered, “communist.” They laughed in his face and corrected him, “No, you are an anarchist.”

Although he never joined the CNT, he shared the exiles’ anti-Franco fervor. As a trusted union militant without a record with the Paris police, he was asked to shelter his hero, Sabate, who was on the run from Spanish and French authorities. The two men bonded immediately and the short time that they spent together set Lucio on a path of resistance that would last throughout his life. Sabate eventually turned himself in, to avoid extradition to Spain where he would be garroted—but he left his weapons hidden with Lucio. (Sabate later resumed his activities and was killed while entering Spain in 1960.)

Knowing the strain that Sabate’s incarceration put on the resistance movement, Lucio took it upon himself to contribute to the cause that he held so dearly. He began a series of bank expropriations through which he amassed large sums of money, none of which went to his own coffers but rather to the anti-Franco resistance. Never viewing himself as a criminal, these robberies were the only means he could find to fund the activities of his fellow anarchists. He never shot anyone and humbly recalls wetting his pants under the intense pressure of the moment.

Having trained himself in the art of printing, the next course of action was to produce currency and other documents (passports, ID cards, drivers licenses, etc.). Crossing the border was a life-and-death matter for militants, so he reproduced them perfectly. Since the government limited the freedom of movement, they decided to “become the government” by forging passports.

(more…)

Realizing the Impossible: Art Against Authority

Realizing the Impossible: Art Against Authority

Realizing the Impossible: Art Against Authority

Josh MacPhee and Erik Reuland, eds.

319 pp.; AK Press, Oakland and Edinburgh, 2007

Reviewed by Alan W. Moore

The artist in capitalist society is necessarily a revolutionary. S/he is as well necessarily an entrepreneur. Between these two positions lies a wide gulf in understandings. The artist must strive to change society according to a vision, because s/he does not fit. Creativity is not an absolute good and value in this society, and the artist is absolutely committed to creativity. Still, the artist must survive, and so must do what that requires.

What is that? What is longed-for utopia and what is impinging reality? The divide between our dreams of a perfect world and the realities of our lives, between what is necessary and what is desired has shifted. The Wall is gone; new walls are a’building. The organizers of the Documenta 12 exhibition recently proffered the assertion, “Modernity is our antiquity.” In finding new coordinates for radical position-takings today, we are continuously picking through those ruins for stuff we can use.

Realizing the Impossible bespeaks an exciting upsurge of attention to a world of dynamic committed artistic practices, past and present. It is largely a book on contemporary art, concerned first with explicating artistic practice now and in the postmodern past.

Realizing begins with Christine Flores-Cozza’s interview with the late venerable Mexican-American artist Carlos Koyokuikatl Cortéz. Influenced by Rivera, Orozco and Posada, Cortéz’s stark woodcut graphic style grew out of the IWW milieu in Chicago, also home to a long-time Chicano/a community. Bill Nowlin interviews another strong-lined graphic artist, the Italian Flavio Costantini who portrays the historical actors of continental anarchism in shadowbox vignettes. Icky A interviews Clifford Harper, the English illustrator and “classic working class anarchist” who drew Class War Comix and the Utopian Visions series in the mid-1970s. These interviews comprise some of the most valuable parts of Realizing, primary documents that point to realms of hidden history.

A key group of essays in Realizing reach back to modernism. Patricia Leighten makes the broadest case for anarchist influence in the pre-World War I French avant garde. (She wrote Re-Ordering the Universe: Picasso and Anarchism 1897-1914, a key part of the social art history which revisioned classic modernism in the late 1980s.) In a chapter from her forthcoming book, she investigates the relationship between satirical cartoons and modernist abstraction, particularly the cubism of Juan Gris and Picasso. Like Antliff, she reads artists’ illustration work back into their oeuvres. Previous scholars followed the separations endemic to the period, during which each mode had its own salon. The new scholarly tack, influenced by the pressure of cultural studies, is now general (think Andy Warhol’s shoes). It was signaled as legit in 1990 with the Museum of Modern Art’s titanic “High & Low” exhibition.

(more…)

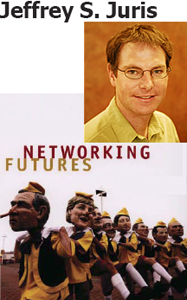

Inside Networked Movements: Interview with Jeffrey Juris

Inside Networked Movements: Interview with Jeffrey Juris

by Geert Lovink

Jeffrey Juris wrote an excellent insiders story about the “other globalization” movement. Networking Futures is an anthropological account that starts with the Seattle protests, late 1999, against the WTO and takes the reader to places of protest such as Prague, Barcelona, and Genoa. The main thesis of Juris is the shift of radical movements towards the network method as their main form of organization. Juris doesn’t go so far as to state that movement as such has been replaced by network(ing). What the network metaphor rather indicates is a shift, away from the centralized party and a renewed emphasis on internationalism. Juris describes networks as an “emerging ideal.” Besides precise descriptions of Barcelona groups, where Jeff Juris did his PhD research with Manuel Castells in 2001–2002, the World Social Forum, and Indymedia, Networking Futures particularly looks into a relatively unknown anti-capitalist network, the People’s Global Action. The outcome is a very readable book, filled with group observations and event descriptions, not heavy on theory or strategic discussions or disputes. The email interview below was done while Jeffrey Juris was working in Mexico City, where studies the relationship between grassroots media activism and autonomy. He is an Assistant Professor of Anthropology in the Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences at Arizona State University.

is an anthropological account that starts with the Seattle protests, late 1999, against the WTO and takes the reader to places of protest such as Prague, Barcelona, and Genoa. The main thesis of Juris is the shift of radical movements towards the network method as their main form of organization. Juris doesn’t go so far as to state that movement as such has been replaced by network(ing). What the network metaphor rather indicates is a shift, away from the centralized party and a renewed emphasis on internationalism. Juris describes networks as an “emerging ideal.” Besides precise descriptions of Barcelona groups, where Jeff Juris did his PhD research with Manuel Castells in 2001–2002, the World Social Forum, and Indymedia, Networking Futures particularly looks into a relatively unknown anti-capitalist network, the People’s Global Action. The outcome is a very readable book, filled with group observations and event descriptions, not heavy on theory or strategic discussions or disputes. The email interview below was done while Jeffrey Juris was working in Mexico City, where studies the relationship between grassroots media activism and autonomy. He is an Assistant Professor of Anthropology in the Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences at Arizona State University.

GL: One way of describing your book is to see it as a case study of Peoples’ Global Action. Would it be fair to see this networked platform as a 21st century expression of an anarcho-trotskyist avant-gardist organization? You seem to struggle with the fact that PGA is so influential, yet unknown. You write about the history of the World Social Forum and its regional variations, but PGA is really what concerns you. Can you explain to us something about your fascination with PGA? Is this what Ned Rossiter calls a networked organization? Do movements these days need such entities in the background?

JJ: I wouldn’t call my book a case study of People’s Global Action (PGA) in a strict sense, but you are right to point to my fascination with this particular network. In many ways, I started out wanting to do an ethnographic study of PGA, but as I suggest in my introduction, its highly fluid, shifting dynamics made a conventional case study impossible. A case study requires a relatively fixed object of analysis. With respect to social movement networks this would imply stable nodes of participation, clear membership structures, organizational representation, etc., all of which are absent from PGA. However, this initial methodological conundrum presented two opportunities. On the one hand, it seemed to me that PGA was not unique, but reflected broader dynamics of transnational political activism in an era characterized by new digital technologies, emerging network forms, and the political visions that go along with such transformations. In this sense, PGA was on the cutting edge; it provided a unique opportunity to explore not only the dynamics, but also the strengths and weaknesses of new forms of networked organization among contemporary social movements.

At the same time, PGA also represented a kind of puzzle: I knew it had been at the center of the global days of action that people generally associate with the rise of the global justice movement, yet it was extremely hard to pin down. Participating individuals, collectives, and organizations seemed to come and go, and those who were most active in the process often resolutely denied that they were members or had any official role. Yet, the PGA network still had this kind of power of evocation, and, at least during the early years of my research (say 1999 to 2002), it continued to provide formal and informal spaces of interaction and convergence. In this sense, it seemed to me that figuring out the enigma of PGA could help us better understand the logic of contemporary networked movements more generally. On the other hand, the difficulty of carrying out a traditional ethnographic study of PGA meant I had to shift my focus from PGA as a stable network to the specific practices through which the PGA process is constituted. In other words, my initial methodological dilemma opened up my field of analysis to a whole set of networking practices and politics that were particularly visible within PGA, but could also be detected to varying degrees within more localized networks, such as the Movement for Global Resistance (MRG) in Barcelona, alternative transnational networks such as the World Social Forum (WSF) process, new forms of tactical and alternative media associated with the global justice movement, and within the organization of mass direct actions.

(more…)

Seth Tobocman’s Disaster and Resistance

AK is thrilled to publish Seth Tobocman’s haunting and inspiring Disaster and Resistance: Comics and Landscapes for the 21st Century (introduced by Mumia Abu-Jamal). The work outlines pressing social and political struggles at the dawn of the twenty-first century—from post 9-11 New York City, to Israel and Palestine, to Iraq and New Orleans. Fans of Seth’s work will see that his punch has not softened in this new book, which skewers the individuals and institutions reaping havoc across the globe today. In his bold comic style, he chronicles events as they happen, musing not on the instability and fear, but on the struggle to resist the disaster that they would visit upon us.

AK is thrilled to publish Seth Tobocman’s haunting and inspiring Disaster and Resistance: Comics and Landscapes for the 21st Century (introduced by Mumia Abu-Jamal). The work outlines pressing social and political struggles at the dawn of the twenty-first century—from post 9-11 New York City, to Israel and Palestine, to Iraq and New Orleans. Fans of Seth’s work will see that his punch has not softened in this new book, which skewers the individuals and institutions reaping havoc across the globe today. In his bold comic style, he chronicles events as they happen, musing not on the instability and fear, but on the struggle to resist the disaster that they would visit upon us.

Here is a small excerpt from the book: a piece called “Bayou Future.”