Posted on June 28th, 2011 in AK Authors!

Captive Genders: Trans Embodiment and the Prison Industrial Complex, due in August from your own AK Press, is a collection of essays representing years of struggle in the transgender, gender variant, queer liberation movements, and the movement for the abolition of the prison industrial complex. It is the first of its kind—not simply a bridge, but a space for discourse about the linkages between these struggles. A vital new look at how gender and sexuality are lived under the crushing weight of corporal captivity!

We invited Eric Stanley, one of the editors of Captive Genders to interview some of the contributors to give you a better idea of what the book is about, in the words of the folks who have been inspired to take up their pens (or computers, typewriters, word processors). Take a look, and check out the book at akpress.org.

There will be more interviews taking place soon, so stay tuned!

In celebration of the August release of Captive Genders: Trans Embodiment and the Prison Industrial Complex, I asked two of the authors about their contributions to the collection and their current political work. Yasmin Nair is a Chicago-based writer, academic, and activist who has, for the last many years, worked in radical queer and immigration organizing. Ralowe T. Ampu currently lives in a residents hotel in San Francisco, works with Gay Shame and has worked with ACT UP and around the the New Jersey 4 case.

Eric Stanley: It’s now the 42nd anniversary of the Stonewall uprising and it seems for many trans and queer folks, specifically those marginalized by mainstream LGBT politics, little has changed in terms of police harassment, imprisonment and the ways the prison industrial complex destroys trans and queer possibilities. Obviously corporate gay pride celebrations are not the answer, so how do you two think we should situate Stonewall and its commemoration within the present?

Yasmin Nair: Well, for starters, I’d like us to think beyond and outside Stonewall. While clearly an important and historic event, pretending that this was the sole and singular event that somehow caused a radical uprising that then changed queer history for ever erases the fact that such moments of protest were going on before Stonewall, in the 1966 Compton’s riot in San Francisco, for example, or in Chicago, at the raid on The Trip, a gay bar, in 1968.

That being said, the commemoration of Stonewall or any queer uprising presents us with additional problems: on the one hand, mainstream gays and lesbians and straights continually erase the reality that such moments were largely initiated by trans people, hustlers, drag queens, very, very angry queens and queers – precisely the sort of misbehaving misfits they’d like to pretend don’t exist.

On the other hand, as the rest of us work to reinstate the central figures of Stonewall and other events and remind the world that Stonewall was not a Human Rights Campaign fundraiser, I’m also concerned about our unquestioned assumption that simply recovering these “forgotten heroes” is in itself a radical act. Yes, that resistance to authority was deeply important, but what were its long-term effects? And how did that resistance eventually become an anti-capitalist, anti-PIC movement as well? Well, we know that it did not, and what I see over and over again is a kind of recovery, which takes the form of “Stonewall was a riot,” or “Let’s not forget the drag queens,” but nothing beyond a fetishistic reclaiming of sexual identity as some kind of originary marker of radical politics. I’m impressed by any movement that challenges the status quo, but I also need to be clear on what that challenge represents and against whom.

Forty-two years later, we still see queers and straights being targeted for “sex crimes,” we still see the PIC growing in its capacity to profit from the incarceration of the economically and politically vulnerable, and there are now cases where people are being put in jail for debt, a resurrection of the long-ago debtors’ prisons. A lot of queers, especially the ones who don’t conform and can’t get jobs with health care and benefits, end up penniless; a lot of the drag queens and hustlers who participated in riots ended up bereft. I’m not interested in recovering any of them as lost heroes/heroines; I want to see more of a discussion about how they weren’t just screwed over by people who couldn’t stand their sexual identity, but by capitalism.

Frankly, I’m suffering from hero fatigue, and I’m tired of Pride parades which, even when they resist corporate takeovers, never go beyond some vaguely sexualized idea of a “radical” celebration that does nothing to really think through the neoliberal nightmare we live in.

I think Pride ought to become an occasion for queers to begin staging their own Prides, without corporate sponsorship, but with an awareness of the complications of economic and race issues. Currently, in Chicago, for instance, we have an alternative Dyke March, but it became, over the course of a decade, a predominantly white and middle-class event. Even after it moved locations (first to the predominantly Latin@ west side, then to the largely African-American South Shore) there’s a great deal of talk about alternative politics, but not very much conscious conversation about what it means to, essentially, stage Dyke March in these communities and not very much explicit engagement with people, including queers, who live there. Instead, one day a year, we “take over the streets,” and then disappear. I’ve been to the alternative Dyke three out of the four years so far, and I can see its value as a kind of annual resting space/networking tool for queers with alternative politics, but I wish we would drop the pretense that moving the location is more than just marching in a different place.

I’d also like to see a month-long series of radical events and actions that question the queer fealty to the prison industrial complex and to capitalism while critiquing our collective obsession with identity as some marker of freedom. Over the years, I’ve seen queers increasingly support the systems that incarcerate the most vulnerable and marginalized amongst us, in the shape of hate crimes legislation or by turning a blind eye upon the blatant targeting of queers who engage in public sex, for instance. I’d like to see more of an explicit conversation about how the prison industrial complex not only targets queers but actually requires their support to help further its expansion. And, yes, I’d like us to think about that in terms of capitalism and its deployment of the rhetoric of rights, which we embrace too readily. You’ll note that I don’t simply bracket off gays and lesbians as the problem; I think that too many self-identified “radical” queers buy into the idea that somehow simply claiming queerness as an identity is in and of itself a radical act.

Ralowe Ampu: Within the last few years whenever I’ve overheard “respectable,” “clean,” “decent” folks in the Left talk about remembering riots like Compton’s Cafeteria or Stonewall it’s always been with suspicion. Last time I checked, riots don’t exist in the realm of respectability. My initial response is that the only ethical way to remember Stonewall is with another riot. There’s an interesting idea. That idea relies on a political memory that uses convenient rhythms that can renew and imbue non-profit fiscal cycles with relevance. Such a notion would also play well with the sub-cultural frat-boy circuit that fetishizes and glamorizes such authentic moments of insurgency to further their own ableist agendas. I’m not sure why I’m attempting to conceal my resentment here. For the two milieus I’ve just described it’d be infinitely more useful for us all if they simply remained mum on our riots in their rhetoric, for the sake of maintaining consistency throughout their institutional practice. Wouldn’t that make more sense? Until their institutions have been over-turned and revised? To attempt anything else would be to deny that these riots were moments of the powerless seriously asserting themselves in a hopeless situation. Yasmin rightly assesses the assimilationist machinations of the gay mainstream–these riots can’t be reduced to the theme of a fundraiser nor any other opportunistic distortions. Leading from there into campaigns about gay marriage and the military is in the very least ideologically incongruous and, if you would forgive me, outright profane. Nevertheless, these are the times that we find ourselves in.

Those of us that are disenfranchised by the gay mainstream don’t have the ability to represent Stonewall as a battle against police power because the gay mainstream reproduces their hegemonic narratives. You and I could throw together a flier and wheatpaste it or something, but shy of this riot of the disenfranchised (if that), it won’t receive international mass media coverage. This “anniversary” deserves nothing less. As time marches on, we should be thinking deeper and more thoroughly about the implications that this riot presented to the status quo. It’s precisely what this “anniversary” deserves. So I think that those of us that are marginalized can continue to think about interventions. What would it look like? It’s critical to recuperate our powerlessness and dream of intervention because it’s the best way to commemorate Stonewall without speciously memorializing it as a sign of progress.

Eric Stanley: You both, in different ways, call for an expanded understanding of the PIC to include spaces and ideologies not traditionally understood as such. For example: Yasmin, in your piece, “How to Make Prisons Disappear: Queer Immigrants, the Shackles of Love, and the Invisibility of the Prison Industrial Complex,” you call on us to understand the ways the “good immigrant vs. the bad immigrant” binary is maintained is in part a product of the PIC. In other words, while you do want us to pay attention to detention centers, you ask us to consider the entire discourse more broadly. Can you tell us more about that?

Yasmin Nair: Yes, those sorts of binaries are crucial to the discursive strengthening of the PIC. The best example of that has come about in my city, Chicago, where DREAM Act activists, predominantly undocumented youth who would benefit from the legislation, have used the rhetoric of “coming out” as an explicit form of “queering” the movement. A significant number of them, perhaps even the near majority, are in fact queer, and the discourse of “coming out” allows them to form a kind of solidarity with the gay movement. But it also allows them to emphasize that they are, like the mainstream gays whose support they seek, the “good” undocumented: the high school valedictorians, the ones who go on to universities like the University of Illinois or the University of Chicago and are working towards degrees in Law, the ones who will be “productive” citizens.

But there are many countless numbers of youth, queer or not, who have simply not been able to access the same advantages because they and their parents never “made it” – or who may not want to “make it,” for any number of reasons, including a deep suspicion of the state and its supposed munificence, or because they don’t care for the military component of the DREAM Act. Many of these youth recognize that they, like the majority of undocumented youth, are likely to have to take the military option and have no desire to support the US military regime in their countries of origin and/or around the globe. And these are the youth most susceptible to the PIC, because they offer nothing to the state in return, might be resistant its seductions via the PIC and the military, and lack the economic and cultural capital that is being accessed by the “good” ones. Immigrant’s rights groups are not going to fight the deportations of “slacker” undocumented youth or those who are openly critical of the military component.

In the meantime, in the public eye, such a combined discourse – of good gays and good undocumented youth – allows for a continued perception that only the good ones deserve “rights” – the right to health care through marriage, the right to demand that the PIC incarcerate more people, the right to immigration as long as normative requirements of citizenship are adhered to. In Chicago, what has been most disappointing to me is that an influential if putatively left/progressive bloc of the city has cleaved mightily to this same discourse of “good immigrant vs. bad immigrant,” without even, at the very least, acknowledging that it is problematic and deeply harmful to far more in the long run or that such a discourse legitimizes the extension of the PIC. This is why a critique of discourse is so necessary.

As someone who wants to see actual change come about, I’m not unaware of the compromises we are sometimes required to make, but it’s one thing to compromise and quite another to willfully erase the contradictions with which we find ourselves confronted. The DREAM Acters may well help get the legislation passed, and as someone with several friends who might benefit, I’d be happy to see that happen. But what do we then do about the youth left behind, the ones coerced into military service or the ones who, like, well, so many native-born teens, aren’t able to prove their exemplary status? At no time in history have those who won their “rights” ever then turned around and worked with or for the ones left behind – the reality of political success demands that you move on and forget the rest.

(more…)

Posted on June 28th, 2011 in AK Distribution, Reviews

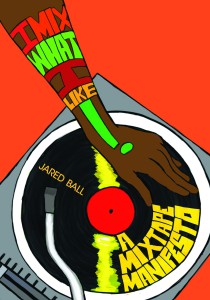

Hopefully all you news hounds have been faithfully following the recent press coverage related to AK Press releases such as I Mix What I Like, Revolt and Crisis in Greece, and Peace, Love & Petrol Bombs. But we’re not the only ones publishing kick-ass books these days; several of our distributed publishers have gotten some great recognition recently for their recent titles, and we highly recommend all of these … read on and check them out, if you haven’t yet!

The Listener, a new graphic novel by artist and Mecca Normal guitarist (and Gruesome Acts of Capitalism author) David Lester, and published by Arbeiter Ring, has been getting quite a lot of press. Besides the early reviews we’ve already mentioned, it’s gotten write-ups from the Baltimore City Paper and The Onion A.V. Club. And most recently, Publishers Weekly called The Listener “a dense and fiercely intelligent work that asks important questions about art, history, and the responsibility of the individual, all in a lyrical and stirring tone.” And School Library Journal, calling it one of the best books of the year so far(!!), recommended it in the “Adult Books 4 Teens” category: “This is an excellent graphic novel for teens who appreciate history or have an interest in contemporary politics as well as for young artists and writers who can both learn from and appreciate the storytelling that brings the past to life while focusing on a character’s present. From the opening passages, the tension never lets up, yet the story remains accessible and memorable.

The Listener, a new graphic novel by artist and Mecca Normal guitarist (and Gruesome Acts of Capitalism author) David Lester, and published by Arbeiter Ring, has been getting quite a lot of press. Besides the early reviews we’ve already mentioned, it’s gotten write-ups from the Baltimore City Paper and The Onion A.V. Club. And most recently, Publishers Weekly called The Listener “a dense and fiercely intelligent work that asks important questions about art, history, and the responsibility of the individual, all in a lyrical and stirring tone.” And School Library Journal, calling it one of the best books of the year so far(!!), recommended it in the “Adult Books 4 Teens” category: “This is an excellent graphic novel for teens who appreciate history or have an interest in contemporary politics as well as for young artists and writers who can both learn from and appreciate the storytelling that brings the past to life while focusing on a character’s present. From the opening passages, the tension never lets up, yet the story remains accessible and memorable.

And check out this brand-new arrival, the steampunk choose-your-own-adventure What Lies Beneath the Clock Tower by Margaret Killjoy (also the author of the AK Press book Mythmakers and Lawbreakers), published by Combustion Books! It was featured recently on BoingBoing, where Cory Doctorow complimented the author’s “pitch-perfect steampunk sensibility” and continued: “There are many different ways the story can proceed, of course, but if you make your way through to the end, you’ll discover that Killjoy’s not just spinning a shaggy-dog story—there’s a surprising amount of heart and adventure to be had if you’re bold enough to choose the path of heroism.”

And check out this brand-new arrival, the steampunk choose-your-own-adventure What Lies Beneath the Clock Tower by Margaret Killjoy (also the author of the AK Press book Mythmakers and Lawbreakers), published by Combustion Books! It was featured recently on BoingBoing, where Cory Doctorow complimented the author’s “pitch-perfect steampunk sensibility” and continued: “There are many different ways the story can proceed, of course, but if you make your way through to the end, you’ll discover that Killjoy’s not just spinning a shaggy-dog story—there’s a surprising amount of heart and adventure to be had if you’re bold enough to choose the path of heroism.”

Last but certainly not least: Defying the Tomb—a collection of artwork and writings by political prisoner Kevin “Rashid” Johnson, published by our friends at Kersplebedeb—was recently featured on the Black Agenda Report‘s morning shot. It’s also been at the center of a fight between the publisher and Pelican Bay Security Housing Unit, where prison administration has banned the book, alleging “promotion of gang activities.” In Rashid’s own words (from the book): “Repression of “gangs” serves as a fig leaf for the repression of any collective action or organization by the oppressed that does not suit the plans of the oppressor. This dynamic exists in oppressed communities throughout the united states, but like most oppressive dynamics it appears in its most concentrated form within the prison system.” Check out Sketchy Thoughts for more on the banned-book fiasco, as well as links to more information about the prisoner struggles currently taking place at Pelican Bay.

Last but certainly not least: Defying the Tomb—a collection of artwork and writings by political prisoner Kevin “Rashid” Johnson, published by our friends at Kersplebedeb—was recently featured on the Black Agenda Report‘s morning shot. It’s also been at the center of a fight between the publisher and Pelican Bay Security Housing Unit, where prison administration has banned the book, alleging “promotion of gang activities.” In Rashid’s own words (from the book): “Repression of “gangs” serves as a fig leaf for the repression of any collective action or organization by the oppressed that does not suit the plans of the oppressor. This dynamic exists in oppressed communities throughout the united states, but like most oppressive dynamics it appears in its most concentrated form within the prison system.” Check out Sketchy Thoughts for more on the banned-book fiasco, as well as links to more information about the prisoner struggles currently taking place at Pelican Bay.

All of these titles (and thousands of others!) can be ordered directly, by individual customers or wholesale, from AK Press Distribution.

Posted on June 25th, 2011 in Reviews of AK Books

Last week we posted the first section of an interview with Jared Ball, author of I Mix What I Like!: A Mixtape Manifesto on his take on emancipatory journalism, hip-hop, colonialism and black culture in America. We’re very excited to be able to bring you the second part of this great interview by Gabriel San Roman.

Last week we posted the first section of an interview with Jared Ball, author of I Mix What I Like!: A Mixtape Manifesto on his take on emancipatory journalism, hip-hop, colonialism and black culture in America. We’re very excited to be able to bring you the second part of this great interview by Gabriel San Roman.

There’s still time to order the book through akpress.org and receive the I Mix What I Like! installment of the Free Mix Radio mixtape! Just order before July 12th and we’ll include the CD for free!

Be sure to check out the original post, which appeared in The OC Weekly on Wednesday, July 22nd!

OC Weekly (Gabriel San Roman): A lot of people have popular frustrations with music these days whether it’s what’s on the radio or on the shelves, but they don’t have a way to articulate it. Your book provides helpful information in that regard. Let’s start out with what is called “the Musical OPEC.” What does that term mean?

Jared Ball: The phrase “Musical OPEC” comes from Greg Palast who used that phrase in his discussion in The Best Democracy Money Can Buy. It obviously draws the comparison between the musical companies that control popular music and the organization of petroleum exports, the community that organizes the distribution of oil in the world and the power it wields over our daily lives from the cost of gas to the our choice in vehicles. These music companies and their parent companies really have all the power that they’ve earned through corruption [laughs] and as one person I quoted calls ‘economic terrorism’ to take control over cultural expression and the popular culture of people that are meant to be maintained in a social order that I’m describing as colonialism but could be described in a number of many other ways and often is.

What does this consolidation of music corporations entail and how much control do they have over the music we hear?

These corporations determine everything! They determine what songs go on the radio, what songs get videos, how often they’re played on the radio, what artists get billboards, where they tour, who gets to tour, what venues they get and to a great extent determine who we know to consider to be our favorites and who we never hear from through the simple process of omission and so on. Through a record contract, a corporation gets control over an artist’s product or song, and that ownership allows that corporation to determine through payola, or pay-to-play, how often that song appears in radio, videos, movies or for a video game soundtrack. They make sure that the songs that they own are the songs that we hear most often. It doesn’t mean we won’t hear something else. It doesn’t mean that artists can’t break through that in small pockets and make dents in this thing and have careers with followings though.

Who are “The Big 3” in the music industry?

To become truly popular, to truly dominate the public sphere, you have to be supported by one of three major corporations, Warner Music Group, Universal Music Group and Sony, each one of them owned by larger entities with holdings in all kinds of different business all around the world, and they basically sanction whether or not an artist is famous is not. While we think we like something, or that we have some choice in the matter, for the most part, we have very little and we just respond to what these corporations prefer what we listen to or be aware of and of course most of that is nothing that would intellectually threaten their position of power and dominance. You’re going to get a bunch of songs that are vaguely about love, or shaking it, selling this, or smacking that, or buying this. Very little of what becomes popular will encourage us to become thoughtful people or certainly to have what would be considered radical or dissident ideas.

I MiX What I Like! is just as much about journalism as it is about hip-hop and the mixtape. The two are, of course, interrelated. Given that, do you think that much of music journalism today is lacking in political economy or critical consciousness?

Yeah, certainly in a lot of what is, again, considered most popular. There’s always, of course, exceptions in pockets and even in popular spaces. I’m often impressed by Rolling Stone and some of the journalism they get in that magazine. In general, though, a lot of what we get is fandom and it’s almost a musical equivalent to White House Press Corps press coverage of the White House. It’s like corporate stenographers. It’s more like publicity, promotional work than it is actual journalism. There’s not a lot of critique, or as you’ve said political economy in the questions or the coverage. This is again part of the same problem. The same political and corporate entities that control the cultural expression control journalistic expression. This is why we need to combine radical concepts of journalism, art and mass media communication to circumvent it. One of the major points I’m trying to address is the intent behind the final product. I argue that it is not simply about making money or selling product. It’s really about making sure that we don’t raise fundamental questions about our relationship to this society and how we are going to sustain ourselves in it. These are the questions that if we don’t get serious about asking and answering, we’ll just see the same patterns of negative outcomes continue.

There were two recent headlines in the world of hip-hop that are pretty juxtaposed. Soulja Boy gave a shot out to the slave masters, and Lupe Fiasco was on the O’Reilly Factor on Monday after he made comments about terrorism, Obama, the United States, and its foreign policy. What do these headlines tell us about mainstream hip-hop today?

It’s actually unfortunate that Lupe Fiasco would even go on that program. I don’t see the value of going on the O’Reilly Factor to argue. That aside, as much as I like Lupe, I don’t consider him a true representative of mainstream hip-hop. My point of view is he’s an exception of the rule at this point. Mainstream hip-hop has become so centrist, right-wing, reactionary and anti-thought, that any degree of thoughtfulness seems like a radical break and something new. Lupe is not representative of what is now mainstream hip-hop, but he is more representative of mainstream thinking within hip-hop. He’s got a lot of attention because anytime you call Obama ‘the biggest terrorist’ and you are, to a relative degree, at the top of the game, that’s what will happen. Soulja Boy’s comments are much more to the point; that hip-hop has been forcibly reduced in its public form to being absent of thought or depth. If we were allowed to hear more of the hip-hop community, we would hear more along the lines of what Lupe said then we would of Soulja Boy and similar comments. That is the fear of those that are in control of all this. There is a long history and long line of documentation, overt and some more implicit, to support this. Those in power want to make sure that the popular discussion or the popular image of those that they most need to oppress will be more like a Soulja Boy than like a Lupe Fiasco.

Lastly, a book about mixtapes wouldn’t be complete without one of its own. How can people get a copy of the official I MiX What I Like! mixtape to see how it’s done?

People who get the book through AK Press will get a copy of the mixtape. We’re also asking people to go imixwhatilike.com and send me some sort of proof of purchase and we send them a password to get the digital copy online, or we can send the actual hard copy mixtape out. As much as I’m happy to hear the version we’ve done, one of the points I make in the book is that people should take these concepts with their own expertise and put them together and create versions of mixtape radio and emancipatory journalistic projects wherever they are in their local communities. That’s really how it’s supposed to work. That’s the point of the book; that wherever we are, the genius already exists, the talent already exists. I just think we need to re-politicize them a little bit and people will put it together and do all kinds of things with their own wonderful, brilliant and radically imaginative ways. In any event we can make sure they get a copy of the mixtape if they really want one.

I MiX What I Like! A Mixtape Manifesto is available now. Order the book via AK Press before July 12th and receive a physical copy of the accompanying mixtape featuring Dead Prez, Malcolm X, Head-Roc, Pharoahe Monch and many others. You can also send a photo of yourself with the book at imixwhatilike.com for the digicopy password.

Posted on June 24th, 2011 in AK Allies, AK Authors!, AK Distribution, Anarchist Publishers, Recommended Reading, Uncategorized

Last month I had the great fortune to table for AK Press at the annual Montreal Anarchist Bookfair, one of the most well-attended anarchist events in North America, and a total pleasure. I was also fortunate enough to get a stack of copies of the first book released by Combustion Books, a new publishing project with anarchist principles, started by the editor of AK’s volume on anarchist fiction, Mythmakers & Lawbreakers, and other alumni from SteamPunk Magazine. The books were fresh from the printers, and arrived just in time for the event, and I’ll be damned if we didn’t sell the entire stack. It wasn’t hard. The book is called What Lies Beneath the Clock Tower (Being an Adventure of Your Own Choosing), and at $8, it’s a bargain for nearly endless hours of fun… I figured it was time to call up Combustion Books and get the scoop on what they’re up to, and what other little gems are in the pipeline for the coming year. Margaret, Smokey, and Elena were kind enough to answer my questions …

Let’s start off with an easy one: tell me a little about Combustion Books. Who are you, and what’s your story?

Let’s start off with an easy one: tell me a little about Combustion Books. Who are you, and what’s your story?

Margaret: Combustion Books is a worker-run genre fiction publisher based in New York City. We’re brand new, though the group of us have been working together on radical fiction projects for a number of years.

Your tagline is “Publishers of Dangerous Fiction”–why? What’s dangerous about the fiction you publish?

Margaret: I think the best stories have always been dangerous. I think that stories have a real power, that we build our identities and our lives based on fictions and myths, and we aim to publish stories that challenge the status quo. The stories that really stick with us are the ones that shake up or shape how we see the world, that focus our dreams and help us figure out what we’d like to see in the world. Genre fiction has a rich history of this–Michael Moorcock and Ursula Le Guin come to mind–but a sadly overwhelming number of books are published every year that are just banal and derivative, or even reactionary and conservative.

I find myself going off sometimes about “cultural warfare” as an element of social war or class war or whatever: I’m all about encouraging stories of the underclasses, of the oppressed. I want us to stop fantasizing about being powerful queens and princes and start identifying with people closer to our own situations who learn how to struggle to be free and happy.

Smokey: I would add that all regimes have always banned works of fiction much more than non-fiction which makes sense to me. Fiction has an uncanny power to infect people with new ideas and for many that can be very dangerous indeed. Also most fiction is controlled by a few publishing houses that fear for their bottom-line. That means any work that is not easy to identify and sell is dangerous. We are interested in publishing books and works that might be hard to publish elsewhere because they are groundbreaking, using unusual formats, saying unpopular things, and so on.

Can you tell me a little about the structure of Combustion Books? Are you a collective? Is it a completely volunteer-run project, or do you intend on paying yourselves?

Margaret: We are a collective and make our decisions by consensus but with a large degree of individual autonomy in our work. Ideally, we’ll be paying ourselves a bit through this work–because publishing is indeed a lot of work–but we’re committed to anti-capitalist practice. Smokey can probably explain that better though.

Smokey: We have had to struggle quite a bit around the issue of intellectual property rights, royalties and capitalism in general in designing Combustion Books. We in Combustion Books are radicals and believe that capitalism is a poor engine for disseminating ideas we care about. Thus we have had to rethink every aspect of how books get published. In short we want to create a community of authors, publishers and artists that work together and support each other while making the works available to the largest number of people. We do not believe in property rights (royalties) and are moving more to the model many radical and even progressive musicians have moved towards. We pay for the actual work, for both writers and artists, and make every step both participatory and transparent. The authors and artists keep the rights and we provide them money for allowing us to publish they work but that is it. If they ever feel we are not doing a good job or for whatever reason they are not content they are free to sell their work elsewhere. We want to be able to push just as hard titles that will only ever sell a thousand copies as we would for some blockbuster. The key for this new approach to work is that artists, writers, editors, people distro-ing, etc. all feel they are partners in the project that is Combustion Books.

(more…)

Posted on June 24th, 2011 in Events

Join the AK Press collective for our annual “F*ck the Fourth” sale at our Oakland warehouse!

We’ll be opening up our stock of over 4,000 titles to the public, with everything at 25% off, including books, t-shirts, DVDs, pamphlets and magazines. There will also be tables of bargain books (good stuff!) for just $1, $3 or $5!

Plus music from local DJ’s, and free refreshments (vegan-friendly)! Bring your friends and neighbors, it’s not to be missed!

For those of you not in the Bay Area, you can still take advantage of the deals by placing your order online between now and July 4th. You’ll get a 25% discount on anything we sell! See http://www.akpress.org for details.

Posted on June 22nd, 2011 in AK Authors!, Current Events

Members of the Occupied London collective, authors/editors of our new release Revolt and Crisis in Greece, wrote a great op-ed piece on the renewed turmoil in Greece and the creative strategies and responses of the protest movement that’s just been posted up on Al Jazeera. Here’s a snippit from the article by Hara Kouki and Antonis Vradis:

Members of the Occupied London collective, authors/editors of our new release Revolt and Crisis in Greece, wrote a great op-ed piece on the renewed turmoil in Greece and the creative strategies and responses of the protest movement that’s just been posted up on Al Jazeera. Here’s a snippit from the article by Hara Kouki and Antonis Vradis:

Grassroots politics flourish in Greek turmoil

As politicians become embroiled in massively unpopular “austerity measures”, protesters find creative avenues of change.

[…]

On June 15, in the immediate aftermath of the violent General Strike demonstration, and following days of negotiations with his parliamentary opposition, Prime Minister Papandreou threw in the towel by announcing a government reshuffle. Snap elections and perhaps a swift round of short-lived governments are now likely; the prime ministerial seat has become unenviable, if not near-untenable.

For the people gathered in Syntagma, the intense political manoeuvring in the corridors of parliament seems to matter little. Theirs is a mass mobilisation that draws a distinction between representational and grassroots politics. Political parties seem unlikely to come to a halt over developments in the upper echelons of power. For them, the Memorandum is not just a sum of persons or abhorrent policies, but a system of power that has misruled the country for 30 years, bringing it to the edge of collapse. It is a system of beliefs, values, expectations and political roles and identities that cannot be abolished simply by replacing the head or members of the government.

The people in the squares have started, again, to believe that they have the freedom and the responsibility to act; they are urging radical change through the creation of different personal and social relations.

By now, the distance between the people and their representatives might seem unbridgeable; as the old system of government crumbles under the burden of sovereign debt, a new, grassroots system of politics is starting to make itself heard from the ground.

Be sure to head over to Al Jazeera to read the whole thing. Hopefully we’ll see more commentary from the Occupied London collective in the international news in the coming days.

And, be sure to check out Revolt and Crisis; it’s 25% off on the AK Press site for a few more weeks, and well worth the money. Really a great analysis and background on the current situation in Greece and how things came about; with more and more pundits claiming that the US economy is going the same way as Greece (and an equal amount of doubt as to the validity of those claims), folks should definitely check this book out … !

Posted on June 21st, 2011 in Reviews of AK Books

Thanks to Gabriel San Roman for conducting this great interview! Take a look to see what the hip-hop mixtape has to do with colonialism, how the mixtape can be used as a journalistic tool, and even how the nickname The Funkinest Journalist came about.

Check out the original posting of the article in the OC Weekly.

Order the book at akpress.org between now and July 12th, and get a free copy of the I Mix What I Like! edition of the Free Mix Radio revolutionary mixtape!

As I MiX What I Like! A Mixtape Manifesto pays homage in title to a series of articles written by the late freedom fighter Steve Biko, Dr. Jared A. Ball’s first book declares hip-hop’s mixtape as a principle means by which to “fight the power.” Provocative in his analysis, the “Funkinest Journalist” positions the “hip-hop nation” as an internal colony in need of a liberated form of expression. The music industry, Ball argues, has succumbed to ever increasing corporate consolidation homogenizing what is heard on mainstream commercial radio.

The Associate Professor of Communication Studies at Morgan State University offers a critique of the politics of popular culture that lends a framework of understanding to all those who routinely turn off the dial in disgust and wonder aloud about what happened to the state of music these days. Better yet, Ball offers a detailed vision of a politicized mixtape as an empowering alternative. Boots Riley of the Coup says of I MiX What I Like, “With this book, Jared Ball correctly and cogently posits hip-hop in its rightful place – as the most important literary form to emerge from the 20th century.”

OC Weekly (Gabriel San Roman): For starters, what does your nickname, “the Funkinest Journalist,” say about the nature of your work and how did you get that nickname in the first place?

Jared Ball: It actually started when I began doing a low powered FM radio program in Washington D.C. and we all needed nicknames. I had just been reading Rickey Vincent’s work on the relationship and history of funk music to hip-hop. I needed a nickname and I took that one, “the Funkinest Journalist,” meaning that I wanted to practice the kind of journalism that represented what Vincent was talking about in terms of what the funk is, this universal revolutionary principal, African cosmological symbol, and cultural expression, giving something new and revolutionary to the world. So I just took the nickname and ran with it for the program.

Let’s talk about your journalism as it relates to your new book, I MiX What I Like, and the concept of the mixtape. It’s popularly seen as a free collection of songs from artists between albums these days, but what’s its history rooted in hip-hop?

The mixtape, as you said, has a lot of different applications and various definitions and as it emerged out of the DJ culture of the late ’60s/early ’70s around the world, I’ve just tried to argue, picking up something Angela Ards said in an essay some years ago, that the mixtape was really hip-hop’s first mass medium, a national and dissident one. In that sense, the mixtape has a particular and specific relationship to hip-hop as opposed other communities and other various forms that it took, or takes.

What, then, do you see as its current potential as you put forth in your book?

Black and brown progenitors of hip-hop, or this “hip-hop nation” as some people call it, still have the same colonized and antagonized relationship to the United States that they always had. The mixtape, then, should still be used as a form of underground emancipatory journalism that is still a great space and is still used in hip-hop in a variety of ways to circumvent corporate and colonizing media structures. I’m arguing that it could be politicized and be put more to that use and purpose. It’s still very popular in a commercial sense. It’s still one of the best ways that artists promote themselves and corporations use to promote their artists in advance of official album releases. Within hip-hop, the mixtape still has a particular cultural relevance that it doesn’t have in other communities that makes it a viable source for organizers to use as an underground emancipatory press in the twenty-first century.

When people read I MiX What I Like, they’re going to be thinking a lot about Internal Colonialism Theory (ICT) because that’s what the book really starts out with. Why do you think that’s of vital importance to the context of the mixtape as an emancipatory form of journalism?

The phrase “emancipatory journalism” comes from Professor Hemant Shah at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. Fifteen years ago now, he coined this philosophy of journalism that had been, and could be and should be practiced by colonized communities and nations around the world, and held that oppressed communities needed a different philosophy of journalistic practices to deal with the oppression that they faced. Building on a long line and history of people theorizing Black America as an internal colony, I just wanted to put those two concepts together and apply them to the mixtape, which has become for me my favorite form of communication over the years. In interviewing him and reading his work, he agreed actually that what I was trying to do fit the model and made sense, so I just kept running with it. Basically, if you are going to make in 2011 an argument that a low-tech, underground mass medium be developed for radical journalism and cultural expression to take place you have to go through a lot to justify that claim and to justify the reasoning behind applying this thing called emancipatory journalism to Black America. That’s why I spend so much time in this book trying to deal with this concept of colonialism to say that Black people have been colonized just like many others around the world and even others within this country.

Coming from that political context, the mixtape, becomes an avenue for excluded dialogue and music, does it not?

Most definitely! We need to stop talking so much about democracy, freedom and equality and start really talking about the political nature of communication, the political nature of media in the context in which hip-hop developed and the context in which the mixtape found itself in the margins then and now. The purpose is to use all of that to say let’s have some other discussions in general about where we all are politically and so on and see if some new forms of organization and movement can emerge.

Stay tuned for Part II of our interview as Dr. Ball and I discuss the Big 3 “Musical OPEC,” music journalism, Lupe Fiasco, Soulja Boy, and how you can get the I MiX What I Like mixtape.

Posted on June 13th, 2011 in Uncategorized

Peace, Love & Petrol Bombs, D.D. Johnston’s first novel, and the second title in our new fiction series, has arrived in Baltimore! It should arrive in Oakland any day now, so capital F Friends and those of you who have preordered should be receiving it very soon! If you haven’t yet placed an order for it, don’t worry there’s still time to get it at 25% off the list price of $14.95. Just scoot on over to akpress.org and click the “Buy it now!” button!

Peace, Love & Petrol Bombs, D.D. Johnston’s first novel, and the second title in our new fiction series, has arrived in Baltimore! It should arrive in Oakland any day now, so capital F Friends and those of you who have preordered should be receiving it very soon! If you haven’t yet placed an order for it, don’t worry there’s still time to get it at 25% off the list price of $14.95. Just scoot on over to akpress.org and click the “Buy it now!” button!

In the meantime, whet your appetite with this excerpt in which our protagonist, Wayne finds himself preparing to hit the Greek streets in Black Bloc style with French anarchist, Manette.

In June 2003, Manette and I travelled from London to Thessaloniki. We arrived on a train from Belgrade, which creaked and hissed, straining to stop at the platform. Doors swung open and from different carriages a dozen people emerged into the morning heat. Two men jumped from the first carriage, laughing as they ran down the steps free of luggage. A family passed laundry bags from the train and cursed the broken handles, holding them underarm where the checked canvas had split and pots and children’s toys nosed into the sunshine.

It was cool in the station building—fans motored; a man in a long winter coat picked cigarette butts from the dark slabbed floor—but outside, Thessaloniki sweltered in the morning sunshine. Bus drivers in big sunglasses leant against their vehicles, and nine policemen loitered by a small office. The police looked up as Manette threw her rucksack into the shade, but they slumped back into conversation as she unzipped the top pocket and tugged out her guidebook.

I sighed and leant my rucksack against the wall.

“What,” she said, lifting her sunglasses onto her hairline, “you know the way?” We had slept on trains the previous two nights, and dots of stubble had reclaimed her armpits. “Fuckeeng shut up then.” Beyond the buses, through the haze, cars paused at traffic lights. Engines revved. Now and then a horn sounded. Manette folded the book, trapping the page with her finger, and then she lifted her rucksack and walked into sunshine that hurt my eyes.

“You sure?”

“You want to study the map?” She must have been exhausted; during the night, I had slept on her lap, and so I wouldn’t wake, she had cupped her hands over my ears whenever the train had roared through a tunnel.

In Platía Yardhari, the leaves of trees looked lush above the scorched yellow grass, and the smell of roasting vegetables mixed with the background pong of stalled sewage. There were posters, pasted to walls and stuck on electricity boxes, with pictures of masked figures throwing petrol bombs, and a caption in English: “We promise a warm welcome for the leaders of Europe.”

Flanked by tall pastel-coloured buildings with balconies at every floor, Odhós Egnatías is a wide road with three lanes on either side of the central reservation. We crossed to the shady side, where a waitress struggled with a parasol, and her colleague dragged metal chairs scratching across the pavement. Manette stopped to read the menu, but it was all in Greek. “Are you hungry?”

I shook my head. “Need some water but.”

“We should eat also.”

We walked in silence for a few minutes before Manette pointed ahead. “Look, Petit Fantôme, up there, that must be the…” She turned the page in her guidebook. “The Arch of Galerius.”

“Oh aye?” I dropped my rucksack in the shade and my Tshirt stuck to my skin. Around the arch’s abutments, bikes rested against green railings, and English tourists walked this way then back again, studying carvings that had softened with time. When we pulled our rucksacks on, we both laughed and grimaced as cold sweat licked the length of our backs.

We walked another fifty yards until Manette stopped at a street kiosk. She checked her guidebook and mouthed the words to herself as she stepped to the counter.

“Oríste?”

“Dhío neró parakaló,” she said, pointing.

“Dhío? You want two?” said the man, holding up two fingers.

Manette nodded and passed a note as the seller looked in his money belt for change.

On the far side of the road, audible between cars, Avril Lavigne sang on a crackly radio, as workmen fixed corrugated aluminium across the windows of Benny’s Burgers.

“Look, Benny’s,” I said.

“They fuckeeng expect us then.” When the sun hit the unpainted shutters, the metal glowed as if on fire.

From the third floor of Aristotle University there hung a black banner as big a penalty box, on which was painted “SMASH CAPITALISM” in giant white letters. Loudspeakers played “A Las Barricadas” through an open window and out into the noise of the street. But once we were on the campus, behind the Theology Department, it was all soft-paced and calm. In a square of grass criss-crossed by concrete paths, topless men finished constructing a stage, while others stretched on the yellow turf, or sipped water in the shade beneath trees, holding their arms out when ever they felt some breeze. Manette fixed on a man in a white vest, who was smoking a roll up at the entrance to the refectory. She crept up behind him, placing her hands over his eyes. “Arrette, Police!”

He kicked his chair back and spun round. “Manette, Salut! Tu va bien?”

“Ça va malaka?”

He put his arms around her waist, swinging her feet off the ground as he kissed her cheeks.

“Comment va Paris?”

“Plus de la même chose: grève à la SNCF; grève dans les écoles.”

“Sounds about right. I fuckeeng miss it, you know?”

His hands still held her shoulders with an easy intimacy that made me think that at one time they had been lovers. Eventually, Manette introduced me and Alex clasped my hand as though we were about to arm wrestle. “Come inside, please. You can leave the bags here.”

The room was empty except for a scatter of chairs and a giant drum of water. Alex pulled a can of Amstel from the drum and the water lapped the sides and the cans bobbed like rowing boats. “You want beer? They take all the refrigerators so we keep them cold like this. They take everything from this building, all the computers, everything. But in the Law Building, across there, we have Indymedia Centre, and this is also the base for the medics.”

“Wow.”

“Yes.” We sat with our beers: Manette and Alex sat on plastic chairs; I sat cross-legged on the cool tiled floor. Alex was in his mid-twenties with dark hair almost as short as his stubble. He had the build of a medium-weight boxer, but there was something quiet about the way he sat. “They learn that we will squat this building and they plan to build gates and hire private security. So we go to the Dean of Theology and we say: One way or another we occupy this building. Either you give us the keys and we stay here, look after it, and next term you still have the building; or, we fight your security, we smash our way in, we break everything, and we burn it before we leave. After this, he give us the keys. Anyway, welcome. Stinyássas. To a hot summer.” We tapped our cans together and drank. “So, how you come, by plane?”

“Nah, train. We met some comrades in Belgrade yesterday, then came down overnight.”

“Is good this way, I think. No problems at the border?”

“Nah, no search or anything.”

“And the Serbian comrades, they come also for the manifestation?”

“They cannae get visas, can they?”

“Po-po-po. This is very important. Tomorrow night—tonight is big party, we have bands playing, we drink, we have fun—but tomorrow night we make manifestation for solidarity with the sans-papier, you know?”

“That’s tomorrow night?”

“Yes, yes. Is not us who organise this, but is our friends from Athens. We make the manifestation in the suburbs, where is the homes of many Albanians and other immigrants, so is very important that we do not make the fight then. Not because we are pacifist, but because we do not want to damage the neighbourhood of our Albanian brothers and sisters, you see? Then next day we make the main manifestation, and where we find the police in the most number, there we attack. With the sticks, with the stones, and with the fire.”

In the afternoon, we explored the university and the streets outside. It was summer vacation; bushes grew unpruned and weeds squeezed between paving stones. Political slogans and posters advertising long-passed demonstrations covered the walls. The university buildings were concrete with big windows that reflected the sun, and in-between these modern blocks there were half-excavated Roman remains: the base of a column, an engraved flagstone, a knee-high wall. Near the Law Department, beneath a sunshade suspended between two trees, a man in shorts cooked stew in a big pot, and behind him two women descended a grassy slope, weaving between tents, clambering over guy ropes.

In the evening, we bought red wine and plastic cups, and we sat on the grass with Alex. On the stage, a punk band hacked through a sound check. Then they shrugged and jumped onto the grass, leaving their instruments leaning in the sunshine and the square quiet except for the hum of a Vespa. I watched the riders approach, their shirts billowing as the girl held the boy round the waist. They stopped outside the Theology Building, and everyone looked as they removed their helmets.

“Hey Stavros!”

“Alex, malaka!”

As those around me returned to their conversations, I lay on my back and let the sun shine orange through my eyelids.

I fell asleep like that, and when I woke the sun had gone and people were standing up, pointing and shouting, as a crowd—maybe fifty people—rushed past the Theology Building. They had a road sign on a metal pole, and they were whooping with wild energy.

“You are awake,” said Alex, slapping me on the back.

“Look,” said Manette. “Hristos!”

“You know these malakas?” asked Alex, rolling a cigarette.

People ran from the tents, chanting “No justice, no peace! Fight the police!” They swarmed around the steps of the Philosophy Building, and Manette held my hand as we ran towards them. She called out to Hristos, but the crowd was too loud. There was something of the medieval siege about it; the metal pole, still with the no-left-turn sign attached, was being used as a batter ing ram. It swung backwards and forwards, held by more hands than there was room for. Then the door crashed open and the crowd cheered and surged forward. I could hear smashing before we were all inside. As we ran through the corridors, a punk hit light bulbs with a stick. Someone let off a fire extinguisher. Near the front door, where a noticeboard had been ripped off the wall, a man in a black vest sprayed big letters: “We don’t forget. We don’t forgive. Carlo vive.”

We didn’t realise how many people were in the university until the immigration demo. Then they streamed from every building. There were thousands of us—four, five-thousand of us—squeezing through the university gates, hoisting flags. Some wore bandannas but most didn’t. Some had cameras swinging from their necks and others held cans of beer. Some were running at the side of the march, spray painting the wall of a church. You wanted to scramble to the highest point so you could see it all.

Then, at the crossroads, we saw riot police in the side streets. They were dressed in green uniforms and white helmets, and they held their shields to their chins. Young anarchists ran forward to throw bottles. They stood in the road, swearing and taunting, until their friends put arms round their necks and pulled them back. Sometimes, the police ran forward, shouting and gesticulating, until they were restrained by their colleagues. It was getting hotter and hotter. When the march roared as one, the noise left you feeling winded. “BATSI! GOUROUNEA! DO-LO-FONÉ! BATSI! GOUROUNEA! DO-LO-FONÉ!” Cops, Pigs, Murderers! Cops, Pigs, Murderers! Louder and louder, until you heard it with your whole body and your insides shook.

In the evening, the sun slipped behind the Theology Building, and the darkness seemed to grow out of the shadows. A smell of petrol settled over the university, and we talked so quietly you could hear the chink of empty bottles and the lawnmower buzz of cicadas. “I have heard,” said the American guy, pausing and looking behind him, “that there was a meeting in the Philosophy Building, a meeting of insurrectionists, who say they plan to kill a cop in revenge for Carlo.”

“Fuck,” said the English guy.

“This is the shit I’m talking about, man!” Welsh Rob stretched his legs out on the Labrador-coloured grass. “This is what I’m saying to you; half the people here are fucking crazy. Look,” he said, whispering now, bird-like the way he pecked around for danger, “there are guys staying here who have outstanding warrants for fucking serious shit. I mean, straight to jail shit. Do not pass go, do not collect two hundred pounds shit. Membership of banned organisations, kidnapping, explosives, arson. Decades in jail shit, right?” A Vespa tore through the quiet, and the engine grabbed a breath as the driver changed gears. “And these guys are going outtomorrow, carrying hand guns—”

“You are fuckeeng scared, Rob.”

“Yeah, I’m fucking scared. These guys are carrying pistols because they don’t plan on being taken alive. That’s too much heat, man.”

“You sound like a fuckeeng scared hippy.”

“If someone shoots a cop, they’ll gun us down. Forget rubber bullets, they’re gonna—”

“Nobody shoot a fuckeeng cop. No wonder you so scared; you believe every rumour you hear. Listen, the last time I am at Hyde Park, an old man tell me that the fuckeeng world end on Friday.”

“So?”

“So you believe every rumour you never leave the house, eenit?”

“Look,” said the English guy, pointing at a stripy gecko on the wall of the Theology Building.

“I’m not a pacifist,” said Rob. “I was with the black bloc in Genoa, but I’m staying away from that shit tomorrow.”

Manette stood up, kicking the pins and needles out of her legs. “As long as you have my fuckeeng dinner ready when I get back. I go to find Hristos.” She threw her cigarette away and walked towards the Philosophy Building.

“And you?” asked the English guy. I shrugged and ran after Manette.

“Fuckeeng hippy wanker. As long as I know him he is crying about police brutality, but as soon as anyone start fighting back, he fuckeeng run away.” The Philosophy Building was guarded by a man in an unbuttoned sleeveless shirt, who sat on a broken wooden chair, chewing gum and tapping his palm with a short club. Inside, our feet crunched on broken glass. The paint fumes made you feel drunk, and the slogans were hard to read because so many lights were broken. “By any means necessary.” “The Future is Unwritten.” “Ultras AEK.” “No War Between Nations, No Peace Between Classes.” The shadows, and the people in the shadows, and the closed doors, carried the suggestion of an ambush, so I found myself looking left and right, as if crossing a road.

Climbing the stairs, I stopped on the landing, and through the window I watched the square below: the intense conversations, Alex’s comrades wielding sticks beneath the lights of the Theology Building, the rest of the campus black and quiet, and, beyond that, the city. You could hear the noise of a dog barking in the distance.

At the top of the stairs, at the end of a corridor where the air was thick with petrol, a man stood in boot-cut jeans, wearing his Ray-Bans folded over the V of his polo shirt. “What?” said Manette.

“Is nobody can come in here.”

“We are friends of Hristos.”

“Sorry, is nobody can come in here.”

“Well, fuckeeng tell Hristos Manette come here to see him.”

A female voice said, “Nikos, ti néa?”

“Eva, you know where is Hristos?”

“Ékso, méh Yiorgos.”

“Hristos go out, sorry. Maybe after he come here.” Fumes tumbled through the doorway, intoxicating, like the runaway train smell of diesel.

(more…)

Posted on June 8th, 2011 in AK Authors!, Uncategorized

A few months back when we made the decision to publish Revolt and Crisis in Greece in collaboration with the editors of Occupied London, we were so excited about it that we decided to rush the book out, and send emails far and wide hailing it’s impending release. About five seconds after those emails went out, I got a response from long-time friend of AK (capital F and otherwise), Deric Shannon, who was chomping at the bit to get a copy of the book, and to get at editors Antonis and Dimitris for an interview. Connections were made, wheels were set in motion, and the result is this fantastic, thoughtful interview. If you wanted to know why we thought the world really needed another book on Greece, this should clear it up for you.

A few months back when we made the decision to publish Revolt and Crisis in Greece in collaboration with the editors of Occupied London, we were so excited about it that we decided to rush the book out, and send emails far and wide hailing it’s impending release. About five seconds after those emails went out, I got a response from long-time friend of AK (capital F and otherwise), Deric Shannon, who was chomping at the bit to get a copy of the book, and to get at editors Antonis and Dimitris for an interview. Connections were made, wheels were set in motion, and the result is this fantastic, thoughtful interview. If you wanted to know why we thought the world really needed another book on Greece, this should clear it up for you.

Be sure to check out the original posting on the Anarchist Writers blog!

And don’t worry, Deric. Your copy will be on the way very soon!

The people behind Occupied London have been instrumental in bringing news and analysis from the Greek streets and resistance, both in print and on the Web. When I first heard they were putting a book out with AK Press, I ordered a copy immediately (though it’s yet to arrive). Their reporting and analysis has helped me and others put together a better perspective on the situation in Greece and its connections to the wider anarchist milieu globally. Such (international) reports and analyses are increasingly important in the age of austerity and as struggles against domination generalize across various parts of the globe—particularly if we wish to see these struggles target institutions like capitalism and the state instead of negotiate with them. Good reporting can also help dispel the kinds of myths prevalent among anarchists about things happening in other parts of the globe and remind us of the things we might do in our own communities.

I interviewed Dimitris and Antonis, the editors of Revolt and Crisis in Greece: Between a Present Yet to Pass and a Future Still to Come over the course of a few months. The situation in Greece has been tense, with huge street demos, fascist pogroms, and police attacks on anarchist social centers (to name a few relevant happenings) in the intervening weeks. Thanks to both of you for the time and care you spent with this interview, given the situation on the ground.

1. First, can you tell me a bit about your book. Who put it together? How did the project come about?

The idea for the book came in response to the various corporate and mainstream tributes to December’s revolt that we saw appearing in its first anniversary, in December 2009. We thought, “if that’s how they portray December one year on, imagine what will happen a few years down the line”. It was as if the revolt was almost apolitical, or at least lacking any contradictions — and not causing any in return.

The original idea, then, was to create a collective book that would read December’s revolt from the viewpoint of those who participated in it, from the ground. But in the course of preparing the book, and as the financial crisis was hitting hard here, we realised we could not read December out of this context either. The financial crisis was instigating a series of other crises in its wake — personal, social, political. This is how “Revolt and Crisis in Greece” was born.

We put the book together as an Occupied London project, which meant it was doomed to be as chaotic as most OL projects tend to be — if it wasn’t for the enduring patience of the folks at AK Press, it would be hard to imagine it coming together at the end! All of us involved closely with the production of the book are involved with Occupied London. We invited contributions from friends we found close to us in the streets in December, and with which we’ve felt an affinity since. But we also invited contributions from friends who have moved away from Greece, or who have never even visited, to try get an outsider perspective on the developments there.

At the end, more than fifty people worked to put this book together. The majority were in Greece, but we had contributions from friends in twelve cities, across six countries — a very international project, something we are very happy about!

2. Can you tell me a bit about Occupied London?

In the past, we have tried to describe Occupied London as an “anarchist collective writing on all things urban”. This is true, but still not entirely accurate. We are not exclusively anarchist, we are not exactly a collective and we do write about other stuff, too! But when we first got together in the Fall of 2007, to start producing a wildly irregular journal, this had been our main aim: We were interested in questions about urban revolts but also about everyday life in cities — and London in particular, as this is where we all found ourselves at the time. We also wanted to ask questions about space and place, about displacement, about the uncertainties of living in late capitalist times. And we wanted to ask these questions on an anarchist platform, one that would host all those who wanted to talk to us.

In December 2008 the scope of the project took a dramatic turn. As the revolt was unfolding in Greece, we realised many of the questions we asked were being answered right where many of us had left from. So the focus shifted to the situation in Greece and the blog “On the Greek Riots” (now “from the Greek Streets”) was born. In a way the book was an evolution of our interest and focus on Greece in the past few years.

(more…)

Posted on June 6th, 2011 in Events

-

IT’S ON THIS WEEK!

This Thursday! The I MiX What I Like Book Launch/DJ Soyo Happy Birthday/10th Anniversary for VoxUnion.com party!

June 9, 2011, Ras Lounge, 4809 Georgia Ave NW DC! 6-11p!

IMIXWHATILIKE.COM for all the details you need!

Let’s start off with an easy one: tell me a little about Combustion Books. Who are you, and what’s your story?

Let’s start off with an easy one: tell me a little about Combustion Books. Who are you, and what’s your story?