Posted on January 30th, 2010 in AK Allies, Happenings

Anarchist Café

Friday, March 12th 7-10 p.m.

225 Potrero Ave.(Between 15th and 16th Street) San Francisco

(Close to 9, 22, and 33 bus lines, closest BART 16th/Mission, followed by 15 min. walk or 22 bus down 16th St.)

The Anarchist Café is on!

The Anarchist Café will happen on Friday March 12th from 7-10pm, the night before the Anarchist Bookfair.

We will have food, coffee, tea and performances indoors and a covered hang out space outdoors. We are serving dinner until 9pm or until the food runs out, whichever comes first. As in past years, the cafe will happen at 225 Potrero Avenue in San Francisco. We are asking for a donation of $5-20 at the door, but no one will be turned away. The money will go to support political projects.

Please no drugs or alcohol. Note the earlier ending time, so don’t show up late and get disappointed.

If you are interested in volunteering at the café contact Mike at mikee1051[at] yahoo.com and include what you would like to do (make food, do dishes, or work the door) and the approximate times you can be available for.

Performers can email marcus [at] midnightspecial.net. Please include in your email a brief description of what you would like to do, for how long, your experience and any amplification needs, etc.

See you there!

A café collective

And another Anarchist Café.

Come create even more community. UA in the Bay will be hosting an Anarchist Café/ Brunch on Sunday February 21st, from 1-5pm at our new space at 154 7th St (near Civic Center BART) in San Francisco. We will have food, but feel free to bring some of your own. (we can not heat stuff there, also please bring your own dishes and utensils, since our capacity to wash dishes is minimal for now.) We will set up a play space for Kids. We are asking for a donation of $5-20 at the door, but no one will be turned away. The money will go to setting up our new space as a resource for our community.

Contact Cheyenne at ccc [at] riseup.net if you are interested in performing and include what you would like to do, for how long, and any prop needs, etc.

Anarchist Café/ Brunch

Sunday February 21st, from 1-5pm

154 7th St (near Civic Center BART) in San Francisco

Posted on January 29th, 2010 in AK Authors!, Happenings

A few weeks ago, I posted the schedule for Margaret Killjoy’s Mythmakers & Lawbreakers Spring 2010 tour; I’m pleased to report that the tour was a smashing success! Thanks to all the authors who joined Margaret on the tour, and all of the amazing bookstores, community spaces, and other venues that hosted the tour, and all of the folks who helped to promote the events in their own hometowns … y’all are awesome!

I asked our intrepid anarchist fiction expert for a recap of the tour; here’s what Margaret had to say:

For the past month, I’ve been traveling around the US in my minivan, doing talks about the intersection of anarchism and fiction. In one regard, I could say I’m doing it in promotion of my book Mythmakers & Lawbreakers, but that isn’t really accurate: I’m doing it in promotion of anarchism and fiction.

And the response has been incredible. I genuinely believe that this is something that people have been waiting for: anarchists read fiction, always have. Anarchist write fiction, always have. But we’ve long told ourselves that fiction is frivolous, that history and theory are somehow more important than the fantastic. But in every city I’ve been to on this tour, people have been excited about exploring the ways in which fiction can help enrich political struggle, about expanding the idea of what writing is “useful” or not.

What’s more, talking about something like anarchism through the lens of fiction has brought out a lot of people who’ve never stepped foot in an infoshop before, who are just curious. Letting them know about the rich history of anarchism (and letting them know that some of their favorite writers were anarchists…) has been, well, really rewarding.

This book tour thing has been awesome. I’ve met so many passionate writers (and readers). I’ve got two dates left (one tonight in Seattle, one on Monday in Olympia), but it’s winding down. In Portland, I shared the stage with Ursula K Le Guin to a packed audience of over three hundred, which gave Ursula a chance to speak candidly about her politics and myself an opportunity to reach people I never would have otherwise.

And people are excited about booking events that aren’t just music. The anarchist scene could certainly use more book tours.

If you’re in the Seattle area, please do join Margaret at Left Bank Books tonight, or in Olympia at Last Word Books on February 1. You can read some of the other tour reflections at Birds Before the Storm, or check out this amazing video of Margaret speaking at Powell’s City of Books in Portland, with the legendary Ursula K. Le Guin! Thanks to the great folks at pdxjustice Media Productions for the recording.

Ursula K. Le Guin and Margaret Killjoy – Mythmakers & Lawbreakers: Anarchist Writers On Fiction from pdxjustice Media Productions on Vimeo.

Posted on January 28th, 2010 in AK Allies, AK Authors!

Since most mainstream/Left/liberal accounts of Howard Zinn’s legacy are likely to gloss over the man’s actual politics, here’s a 2008 interview by AK author, Ziga Vodovnik.

——-

An Interview with Howard Zinn on Anarchism

Rebels Against Tyranny

By Ziga Vodovnik

Howard Zinn, 85, is a Professor Emeritus of political science at Boston University. He was born in Brooklyn, NY, in 1922 to a poor immigrant family. He realized early in his youth that the promise of the “American Dream“, that will come true to all hard-working and diligent people, is just that—a promise and a dream. During World War II he joined US Air Force and served as a bombardier in the “European Theatre“. This proved to be a formative experience that only strengthened his convictions that there is no such thing as a just war. It also revealed, once again, the real face of the socio-economic order, where the suffering and sacrifice of the ordinary people is always used only to higher the profits of the privileged few.

Although Zinn spent his youthful years helping his parents support the family by working in the shipyards, he started with studies at Columbia University after WWII, where he successfully defended his doctoral dissertation in 1958. Later he was appointed as a chairman of the department of history and social sciences at Spelman College, an all-black women’s college in Atlanta, GA, where he actively participated in the Civil Rights Movement.

From the onset of the Vietnam War he was active within the emerging anti-war movement, and in the following years only stepped up his involvement in movements aspiring towards another, better world. Zinn is the author of more than 20 books, including A People’s History of the United States that is “a brilliant and moving history of the American people from the point of view of those who have been exploited politically and economically and whose plight has been largely omitted from most histories…” (Library Journal)

Zinn’s most recent book is entitled A Power Governments Cannot Suppress, and is a fascinating collection of essays that Zinn wrote in the last couple of years. Beloved radical historian is still lecturing across the US and around the world, and is, with active participation and support of various progressive social movements continuing his struggle for free and just society.

Ziga Vodovnik: From the 1980s onwards we are witnessing the process of economic globalization getting stronger day after day. Many on the Left are now caught between a “dilemma”—either to work to reinforce the sovereignty of nation-states as a defensive barrier against the control of foreign and global capital; or to strive towards a non-national alternative to the present form of globalization and that is equally global. What’s your opinion about this?

Howard Zinn: I am an anarchist, and according to anarchist principles nation states become obstacles to a true humanistic globalization. In a certain sense, the movement towards globalization where capitalists are trying to leap over nation state barriers, creates a kind of opportunity for movement to ignore national barriers, and to bring people together globally, across national lines in opposition to globalization of capital, to create globalization of people, opposed to traditional notion of globalization. In other words to use globalization—there is nothing wrong with idea of globalization—in a way that bypasses national boundaries and of course that there is not involved corporate control of the economic decisions that are made about people all over the world.

ZV: Pierre-Joseph Proudhon once wrote that: “Freedom is the mother, not the daughter of order.” Where do you see life after or beyond (nation) states?

HZ: Beyond the nation states? (laughter) I think what lies beyond the nation states is a world without national boundaries, but also with people organized. But not organized as nations, but people organized as groups, as collectives, without national and any kind of boundaries. Without any kind of borders, passports, visas. None of that! Of collectives of different sizes, depending on the function of the collective, having contacts with one another. You cannot have self-sufficient little collectives, because these collectives have different resources available to them. This is something anarchist theory has not worked out and maybe cannot possibly work out in advance, because it would have to work itself out in practice.

ZV: Do you think that a change can be achieved through institutionalized party politics, or only through alternative means—with disobedience, building parallel frameworks, establishing alternative media, etc.

HZ: If you work through the existing structures you are going to be corrupted. By working through political system that poisons the atmosphere, even the progressive organizations, you can see it even now in the US, where people on the “Left” are all caught in the electoral campaign and get into fierce arguments about should we support this third party candidate or that third party candidate. This is a sort of little piece of evidence that suggests that when you get into working through electoral politics you begin to corrupt your ideals. So I think a way to behave is to think not in terms of representative government, not in terms of voting, not in terms of electoral politics, but thinking in terms of organizing social movements, organizing in the work place, organizing in the neighborhood, organizing collectives that can become strong enough to eventually take over —first to become strong enough to resist what has been done to them by authority, and second, later, to become strong enough to actually take over the institutions.

ZV: One personal question. Do you go to the polls? Do you vote?

HZ: I do. Sometimes, not always. It depends. But I believe that it is preferable sometimes to have one candidate rather another candidate, while you understand that that is not the solution. Sometimes the lesser evil is not so lesser, so you want to ignore that, and you either do not vote or vote for third party as a protest against the party system. Sometimes the difference between two candidates is an important one in the immediate sense, and then I believe trying to get somebody into office, who is a little better, who is less dangerous, is understandable. But never forgetting that no matter who gets into office, the crucial question is not who is in office, but what kind of social movement do you have. Because we have seen historically that if you have a powerful social movement, it doesn’t matter who is in office. Whoever is in office, they could be Republican or Democrat, if you have a powerful social movement, the person in office will have to yield, will have to in some ways respect the power of social movements.

We saw this in the 1960s. Richard Nixon was not the lesser evil, he was the greater evil, but in his administration the war was finally brought to an end, because he had to deal with the power of the anti-war movement as well as the power of the Vietnamese movement. I will vote, but always with a caution that voting is not crucial, and organizing is the important thing.

When some people ask me about voting, they would say will you support this candidate or that candidate? I say: “I will support this candidate for one minute that I am in the voting booth. At that moment I will support A versus B, but before I am going to the voting booth, and after I leave the voting booth, I am going to concentrate on organizing people and not organizing electoral campaign.”

ZV: Anarchism is in this respect rightly opposing representative democracy since it is still form of tyranny —tyranny of majority. They object to the notion of majority vote, noting that the views of the majority do not always coincide with the morally right one. Thoreau once wrote that we have an obligation to act according to the dictates of our conscience, even if the latter goes against the majority opinion or the laws of the society. Do you agree with this?

HZ: Absolutely. Rousseau once said, if I am part of a group of 100 people, do 99 people have the right to sentence me to death, just because they are majority? No, majorities can be wrong, majorities can overrule rights of minorities. If majorities ruled, we could still have slavery. 80% of the population once enslaved 20% of the population. While run by majority rule that is ok. That is very flawed notion of what democracy is. Democracy has to take into account several things—proportionate requirements of people, not just needs of the majority, but also needs of the minority. And also has to take into account that majority, especially in societies where the media manipulates public opinion, can be totally wrong and evil. So yes, people have to act according to conscience and not by majority vote.

(more…)

Posted on January 27th, 2010 in AK Allies

Sad news from the Boston Globe…

—————-

Howard Zinn, historian who challenged status quo, dies at 87

By Mark Feeney, Globe Staff

Howard Zinn, the Boston University historian and political activist who was an early opponent of US involvement in Vietnam and a leading faculty critic of BU president John Silber, died of a heart attack today in Santa Monica, Calif, where he was traveling, his family said. He was 87.

Howard Zinn, the Boston University historian and political activist who was an early opponent of US involvement in Vietnam and a leading faculty critic of BU president John Silber, died of a heart attack today in Santa Monica, Calif, where he was traveling, his family said. He was 87.

“His writings have changed the consciousness of a generation, and helped open new paths to understanding and its crucial meaning for our lives,” Noam Chomsky, the left-wing activist and MIT professor, once wrote of Dr. Zinn. “When action has been called for, one could always be confident that he would be on the front lines, an example and trustworthy guide.”

For Dr. Zinn, activism was a natural extension of the revisionist brand of history he taught. Dr. Zinn’s best-known book, “A People’s History of the United States” (1980), had for its heroes not the Founding Fathers —many of them slaveholders and deeply attached to the status quo, as Dr. Zinn was quick to point out—but rather the farmers of Shays’ Rebellion and the union organizers of the 1930s.

As he wrote in his autobiography, “You Can’t Be Neutral on a Moving Train” (1994), “From the start, my teaching was infused with my own history. I would try to be fair to other points of view, but I wanted more than ‘objectivity’; I wanted students to leave my classes not just better informed, but more prepared to relinquish the safety of silence, more prepared to speak up, to act against injustice wherever they saw it. This, of course, was a recipe for trouble.”

Certainly, it was a recipe for rancor between Dr. Zinn and Silber. Dr. Zinn twice helped lead faculty votes to oust the BU president, who in turn once accused Dr. Zinn of arson (a charge he quickly retracted) and cited him as a prime example of teachers “who poison the well of academe.”

Dr. Zinn was a cochairman of the strike committee when BU professors walked out in 1979. After the strike was settled, he and four colleagues were charged with violating their contract when they refused to cross a picket line of striking secretaries. The charges against “the BU Five” were soon dropped, however.

Dr. Zinn was born in New York City on Aug. 24, 1922, the son of Jewish immigrants, Edward Zinn, a waiter, and Jennie (Rabinowitz) Zinn, a housewife. He attended New York public schools and worked in the Brooklyn Navy Yard before joining the Army Air Force during World War II. Serving as a bombardier in the Eighth Air Force, he won the Air Medal and attained the rank of second lieutenant.

After the war, Dr. Zinn worked at a series of menial jobs until entering New York University as a 27-year-old freshman on the GI Bill. Professor Zinn, who had married Roslyn Shechter in 1944, worked nights in a warehouse loading trucks to support his studies. He received his bachelor’s degree from NYU, followed by master’s and doctoral degrees in history from Columbia University.

Dr. Zinn was an instructor at Upsala College and lecturer at Brooklyn College before joining the faculty of Spelman College in Atlanta, in 1956. He served at the historically black women’s institution as chairman of the history department. Among his students were the novelist Alice Walker, who called him “the best teacher I ever had,” and Marian Wright Edelman, future head of the Children’s Defense Fund.

During this time, Dr. Zinn became active in the civil rights movement. He served on the executive committee of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, the most aggressive civil rights organization of the time, and participated in numerous demonstrations.

Dr. Zinn became an associate professor of political science at BU in 1964 and was named full professor in 1966.

The focus of his activism now became the Vietnam War. Dr. Zinn spoke at countless rallies and teach-ins and drew national attention when he and another leading antiwar activist, Rev. Daniel Berrigan, went to Hanoi in 1968 to receive three prisoners released by the North Vietnamese.

Dr. Zinn’s involvement in the antiwar movement led to his publishing two books: “Vietnam: The Logic of Withdrawal” (1967) and “Disobedience and Democracy” (1968). He had previously published “LaGuardia in Congress” (1959), which had won the American Historical Association’s Albert J. Beveridge Prize; “SNCC: The New Abolitionists” (1964); “The Southern Mystique” (1964); and “New Deal Thought” (1966).

Dr. Zinn was also the author of “The Politics of History” (1970); “Postwar America” (1973); “Justice in Everyday Life” (1974); and “Declarations of Independence” (1990).

In 1988, Dr. Zinn took early retirement so as to concentrate on speaking and writing. The latter activity included writing for the stage. Dr. Zinn had two plays produced: “Emma,” about the anarchist leader Emma Goldman, and “Daughter of Venus.”

Dr. Zinn, or his writing, made a cameo appearance in the 1997 film “Good Will Hunting.” The title characters, played by Matt Damon, lauds “A People’s History” and urges Robin Williams’s character to read it. Damon, who co-wrote the script, was a neighbor of the Zinns growing up.

Damon was later involved in a television version of the book, “The People Speak,” which ran on the History Channel in 2009. Damon was the narrator of a 2004 biographical documentary, “Howard Zinn: You Can’t Be Neutral on a Moving Train.”

On his last day at BU, Dr. Zinn ended class 30 minutes early so he could join a picket line and urged the 500 students attending his lecture to come along. A hundred did so.

Dr. Zinn’s wife died in 2008. He leaves a daughter, Myla Kabat-Zinn of Lexington; a son, Jeff of Wellfleet; three granddaugthers; and two grandsons.

Funeral plans were not available.

Posted on January 26th, 2010 in AK Allies, AK Authors!

The Institute for Anarchist Studies recently sent out another request for support. This one was written by AK author Josh MacPhee. It’s worth reprinting here, not simply because the IAS deserves as much support as it can get, but because Josh’s letter itself raises some good questions. It insists that anarchists ask ourselves some hard questions…and that we build on, rather simply rest on, the dubious laurels of (increasingly distant) past successes. Good shit. Read on…

**********

Dear Friends and Comrades,

Economic and political landscapes are shifting rapidly. Around the world, people are coming to the conclusion that the institutions of power have failed us. Many are looking for new ways to restructure society. The question is not whether things are changing but rather whether these changes can enable us to make the lives we share qualitatively better. As antiauthoritarians, our duty is to ask the challenging questions as to how the society we create can be the egalitarian one we’d like to see. The Institute for Anarchist Studies (IAS) is an organization that is dedicated to fostering educational space, promoting radical literature, and curating dialogue in order to grapple with these difficult questions.

Many of you remember the 1999 protests in Seattle against the World Trade Organization. Anarchists were running through the streets with spray paint, writing “We Are Winning” on the walls. At the time it felt great, “Yeah, we’re winning!” But enough time has passed to look back and ask the questions: Was there any truth in that statement? What does it actually mean to win? What are we winning?

Well, we have won a Left where a soft, or “lowercase a,” anarchism has become the default political position. Consensus decision making, spokescouncils, horizontalism—these are all assumed in much Left organizing today, and most young people gravitate to the liberatory promises of anarchism. Even among many sectarian groups, when they do public outreach they wrap themselves in the veneer of direct democracy. Many of the values considered part of anarchism have been fully embraced. That’s useful and important, but there are limitations.

There’s not enough honesty assessing the situation we’re in, which makes it difficult to think critically about how to get where we want to go. We have largely failed to give any real intellectual direction to this newfound popularity of antiauthoritarian ideas and actions. Rather than strengthening our tradition so that we can provide vital analysis as well as criticism of both what we are up against and our own self-organization, we have defaulted to a lazy horizontalist position where fuzzy ideas like “affinity” and “diversity of tactics” have replaced serious debate about who we are, what we are doing, and how we are going to overcome the obstacles we face.

This is where the IAS has an important role to play. The IAS supports the development of anarchist theory adequate to the times we live in. Such theory must be rigorous yet flexible, counteracting a troubling tendency toward anti-intellectualism in the movement. Yet it must not be purely academic; it must also be firmly rooted in praxis, emergent from frontline struggles for equality and liberation, and oriented toward the furthering of substantive social change.

We hope to raise much-needed funds to support our ongoing work, including funding writing and research. Over the summer, we were able to fund the writing of three excellent essays:

• “Sienvolando: Snapshots of Art Actions, Popular Power, and Collaborative Networks in Argentina,” by KellyAnne Mifflin

• “Organizing against Capitalism: Translation of Eric Duran’s ‘Creating a Counterhegemonic Economic System,’” by Scott Pinkelman

• “Futures Not (Yet) Chosen: An Antiauthoritarian Vision for South Africa,” by Taylor Sparrow

February 2010 will see the print revival of our journal Perspectives on Anarchist Theory. In March, we’ll be publishing the first book in our collaborative series with AK Press, Anarchism and Its Aspirations by Cindy Milstein. We’d like to be able to expand the amount of research and writing we can fund and publish, but we need your help.

The IAS grant program is entirely funded by the generous donations of people and collectives like you. Your support allows the IAS to grow and nurture anarchist debate and discourse around the world. Please consider making a donation as small or as large as you like! Every little bit helps—from $20 to $200 to $2,000. If you can donate by credit or debit card, consider visiting our online donations page at, where you can also make a monthly donation of as little as $5 to whatever larger amount fits your budget. You can also send a check made out to the Institute for Anarchist Studies to:

Institute for Anarchist Studies

P.O Box 15586

Washington, DC 20003

Another way to contribute is by hosting one of the many speakers on the Mutual Aid Speakers list at an event in your town and donating the honorarium to the IAS. Contribute to the IAS today, and together we will show what a better world can look like, and to the degree our power permits, make it happen.

Sincerely, Josh MacPhee

for the Board of the Institute for Anarchist Studies

www.anarchist-studies.org

Posted on January 25th, 2010 in About AK

Oh hey! Ashley here, the other half of your friendly AK Press shipping and receiving department. You heard from my counterpart Macio a little while ago, so I guess now it’s my turn…

Oh hey! Ashley here, the other half of your friendly AK Press shipping and receiving department. You heard from my counterpart Macio a little while ago, so I guess now it’s my turn…

In the day-to-day, like everyone here at AK, I take care of a lot of odds and ends to keep the warehouse running (I was going to say “running smoothly”, but you know). My main job for the last 2 1/2 years, though, has been helping to make sure our shelves are stocked with great new items as soon as they’re unloaded off the truck, and getting orders out to the countless bookstores, infoshops, distributors, and tablers so they can sell the hell out of ‘em and spread the word. But let me back up a minute.

I was born and raised in Los Angeles’ San Fernando Valley (if you just thought “so she’s, like, totally a valley girl!” you would be technically correct), growing up with all the contradictions and craziness that implies. I inevitably got into punk when I was about 13, and a budding political consciousness was swift to follow. Within a couple years, I self-identified as an anarchist, feminist, and went vegan. I started getting involved in protests of various types around the city, and ended up arrested at the DNC when it was in held LA in 2000. Much to my parents’ initial dismay, this led me to a new group of radical friends, and to become a part of AGC, an LA-based collective that organized workshops, benefits, demonstrations, and concerts for a number of years. Here I got to learn about collective process, and the power that we have as small groups of individuals to work together to raise awareness and create change within our communities. I was set on a path that I’ve followed ever since.

Eventually I moved up to Santa Cruz to attend school at UCSC, where I majored in Community Studies. Community Studies is a really unique program which, fortunately for me, includes a six month field study with a social change organization of our choice. AK Press was the obvious choice for me, and with a little cajoling, I got the collective to agree to take me on as a full-time, unpaid intern! I moved up to Oakland, packed boxes and attended meetings for six months, and eventually wrote my thesis on anarchist organizations that manifest as cooperatively-run businesses. Oh, and the thesis came with a 20-some page comic, featuring me as the narrator and main character, leading the reader though all I’d learned. Did I mention I draw self-indulgent autobiographical comics, and make zines, too? More on that in a second.

After my internship ended, I couldn’t bear to move back to Santa Cruz, so I stayed in Oakland volunteering at AK and working part-time elsewhere until a few months later a shipping and receiving position opened up and I got hired. I’ve been here ever since, still packing boxes and trying to get a handle on running an anti-capitalist business.

Back to the comic and zine-making, I’ve been doing a vegan cookzine called Barefoot and in the Kitchen for a bunch of years now. It’s actually available through AK, if you want to check it out for yourself. Or, if you’re of the go-big-or-go-home mindset, you can wait a little while and buy Barefoot when it’s a real, live, actual book. I’m busily working on creating and testing tons of new recipes, and doing all sorts of comics and other art for the new and improved Barefoot and in the Kitchen book, which is forthcoming from our good friends at Microcosm Publishing in 2011. It’ll be my first book, and it’s really exciting to be in such great company (Microcosm has produced some classics, ranging from Hot Damn and Hell Yeah to DIY Screenprinting and the Chainbreaker Bike Book), and extra exciting to know that when it comes out, AK will have it!

When I’m not packing boxes or trying to write a cookbook, I’m baking for my side-project, Fat Bottom Bakery. We’re an all-vegan baking company, currently selling at events around the Bay Area and taking special orders. I’m also a co-organizer of the recently formed East Bay Vegan Bakesale, which is held in Oakland every other month to benefit a variety of human and non-human animal organizations.

And that’s pretty much it, I guess. Oh, except for my energy drink collection! I also collect bizarre energy drinks (not to drink! Just to look at), mostly from the little corner store down the street from the warehouse. They have some real gems, as you can see in my picture here. Hey, if Lorna gets to talk about her squished pennies, I get to talk about my cans.

Thanks for reading, and see you all around!

Posted on January 23rd, 2010 in AK Authors!, Current Events

AK author, Chris Carlsson, sent us the following note about the situation in Haiti…

———-

Who isn’t horrified at the devastation in Haiti? We all want to do something to help, but following the football ads or Michelle Obama into texting money to the Red Cross is obviously not a sensible approach. Disaster relief is a complicated real-world drama that involves a lot of really skilled people who need incredible back-up and support. I have a good friend who spent two years in Thailand after the tsunami building replacement houses and developing local, on-the-ground institutions to channel the volunteers and aid that were coming in.

There’s no question that our cash donations can help, but we can’t piss them away on the U.S. military, the Red Cross, or any of those mega-nonprofit agencies… Luckily, on the ground in Haiti for the past 20+ years is Dr. Paul Farmer’s organization, Partners In Health . They have clinics around the country and have been providing medical services all over Haiti for a long time. They have done an incredible job of rushing to meet the crisis. I sent ’em $100 a week ago and have since been getting a steady stream of daily reports. Here’s today’s (Friday, January 22):

There’s no question that our cash donations can help, but we can’t piss them away on the U.S. military, the Red Cross, or any of those mega-nonprofit agencies… Luckily, on the ground in Haiti for the past 20+ years is Dr. Paul Farmer’s organization, Partners In Health . They have clinics around the country and have been providing medical services all over Haiti for a long time. They have done an incredible job of rushing to meet the crisis. I sent ’em $100 a week ago and have since been getting a steady stream of daily reports. Here’s today’s (Friday, January 22):

PIH’s surgical teams continue to race against time to provide surgical care to earthquake victims in Port-au-Prince. Operating rooms at the central general hospital (HUEH) in Port-au-Prince are fully operational again after being temporarily evacuated on yesterday in response to the aftershock. PIH is still coordinating the relief efforts at HUEH and reports having 12 operating rooms opened 24 hours per day. Across the country, we have a total of 20 operating rooms up and running.

To date, PIH has sent 22 plane loads with 144 medical volunteers – orthopedic surgeons, anesthesiologists, surgical nurses and other medical professionals – and several thousand pounds of medical supplies to support the more than 4,500 PIH health care providers already in Haiti.

Despite these accomplishments, our teams throughout the country continue to report a great need for additional medicines (antibiotics, anesthesia and narcotics), medical equipment (anesthesia machines and x-rays), medical supplies (IVs, tubing, irrigating saline), and water.

“There are very sick people and too little space and time,” reported PIH Women’s Health Coordinator Sarah Marsh from our hospital in St. Marc. She added that we will lose more patients to infection in the coming days if we don’t find additional medications, and explained that is only for lack of supplies – not patients – that the surgical team risks performing more operations. A volunteer orthopedist also working from St. Marc stressed that we will need full medical teams on site to manage dressings, skins grafts and other post operative care for another 6-8 weeks.

Our sites in the Central Plateau and the lower Artibonite are dealing with increasing numbers of patients and families seeking both medical treatment and refuge from devastated Port-au-Prince. Finding space and beds for post-operative care has become the next major challenge. In Cange, PIH’s 104-bed facility is overflowing: the church is serving as a triage center and the school as a recovery room. People are arriving in Cange at all hours of the day and night; many simply have nowhere to go.

“Our houses were crushed and our businesses destroyed. So we came to Cange,” said one man who arrived in a bus with 12 relatives, including his mother-in-law who was critically injured. In Belladaire, near the border with the Dominican Republic (DR), up to 1,000 people are camped out at PIH’s hospital in temporary shelter, searching for family members and medical treatment. We expect that people will continue to return to the countryside, having lost their family, livelihoods, and homes in the capital city, and meeting the needs of this displaced population will be a major task in PIH’s long-term rebuilding efforts.

Finally, recognizing that many of our own Haitian staff, who are working tirelessly to save the lives of others, have also lost their own families and friends, PIH is also developing a post-trauma mental health and social service program to serve both staff and patients.

The task ahead is a monumental one. And even as we heal wounds, mend broken bones, and provide basic necessities (food, water, shelter), its true magnitude grows before our eyes. But we know from 20-plus years of accompaniment the resiliency of the Haitian people. Through poverty, strife, hurricanes, disease and hunger, our Haitian friends and colleagues continue to amaze us. Their determination, spirit, and ability to overcome and survive is inspirational and humbling.

Partners In Health is determined to do whatever it takes, for as long as it takes, to ensure that their struggle succeeds.

Posted on January 22nd, 2010 in AK Authors!

This month AK Press released a nifty new book for those with an interest in collectives. Come Hell or High Water is an insightful little tool for those new to egalitarian groups, die-hard vets, and even those who left collectives long ago in disgust.

This month AK Press released a nifty new book for those with an interest in collectives. Come Hell or High Water is an insightful little tool for those new to egalitarian groups, die-hard vets, and even those who left collectives long ago in disgust.

But hey, who the hell cares about collectives anyway? Don’t people just get burned out, frustrated, feel alienated, and end up burning their bridges? Yeah, actually, that happens a lot. Whether or not you think there’s any place for collectives in the struggle for fundamental social and economic change, it ought to give one pause to wonder why we act so poorly in groups meant to be egalitarian. And if a group of like-minded people pursuing a similar goal can’t function responsibly, how do we get to that great day with no gods, no masters? After eight years in the AK Press collective, I can tell you folks, it ain’t gonna happen overnight.

While you ponder these weighty dilemmas, see what Delfina Vannucci and Richard Singer have to say about working collectively. And for an excerpt from the book, go here.

——

Q: How did Come Hell or High Water originate (what, in your collective experiences, led you to write a book about “collective process gone awry”) and how did you come to coauthor the book?

Delfina Vannucci (DV): Richard and I had friends in common, but we had not been in any of the same collectives nor groups with any of the same people. When we started talking about the problems that we had each experienced, we saw that there was a broader issue there. We’re both bookish sort of types who are interested in writing, so writing a small book to try to shed light on these issues made sense for us. We wanted to create the resource that we wished we ourselves had had.

As you can imagine, the book is based on personal experience. I haven’t mentioned any particulars that might personalize what is meant to be a broad resource, broad enough for anyone to find something in it that rings true, so I won’t go into any details. Even though it’s been several years, I’m still pretty shell-shocked.

Richard Singer (RS): Speaking for myself, the first thing in my collective experiences that comes to mind is the fact that I had witnessed a number of situations in activist or political groups (usually collectives) in which people were accused of something or ostracized for something without being given a fair hearing. This was one of the first things I witnessed when I joined the anarchist movement in 1997, when a guy I was doing some organizing with got accused of some weird behaviors, and I was told that I should dissociate myself from him based on some rumors relayed to me by a couple of people. When I said I would like to see some proof via a fair hearing, I got shunned for “defending” him, without any recognition of the problem I had with the process.

I witnessed this sort of thing happening a few times, with people being ostracized without a fair hearing, meetings being held about people behind their backs, etc. (Once I went to a dinner being held by some people in a bookstore collective that I was briefly involved in, the purpose of which meeting was to discuss their complaints about a member whom they deliberately had avoided inviting. It wasn’t until after I experienced the whole event and digested it a little that I realized how wrong that was, and swore never to go to a meeting like that again.) Then, not surprisingly, somewhere down the road, in 2002 or so, the same sort of thing happened to me.

I don’t really want to get into this one (I can’t stress how much I don’t want to get into it!); I don’t even want to get into defending myself against nasty claims that I felt were just gross mischaracterizations or discussing who was crappier, etc. (I was a bit crappy too, I admit that freely.) But I do want to mention this one sort of thing that went on which very much connected to the other things I mentioned above: Things were said behind my back (on lists I was excluded from and meetings that I wasn’t attending) and there were major, obvious violations of what we would commonly refer to in conventional society as due process. And, at one point, there was a real lack of transparency. There was some open discussion, but then there was this other level of discussion that was not open at all—which I did not even find out about until much later—and that phenomenon was all too familiar to me…

Of course, there have been some other tendencies that you might say “inspired” me… For instance, the phenomenon of people who claimed they had no interest in hierarchy actually taking hierarchical roles for themselves (sometimes in rather subtle ways, but it was clear to me and some other people what was really happening).

But I could go on about this stuff for a long time…enough to write a book about it! So I’ll stop myself now and get to the part about how this project actually came into being…

In 2002-03, shortly after the worst of my own experiences, I got involved in forming a Staten Island-based collective with Delfina, her boyfriend Mike (who also, incidentally, had been on my side in “defending” that guy back in ’97) and a couple of other people. Because of the experiences that both Delfina and I had immediately prior to forming this group, and also because of some experiences that I had with a group that we actually tried to be connected to at first, we were already discussing a lot of these issues before we ever got into the project. Then, while we were all busy doing a bunch of other stuff (political tabling, a blog and Web site, helping with an eco fest…), Delfina mentioned to me that she had started working on a Web site related to her recent experiences, collective process, and ideas about consensus. Naturally, the idea very much clicked with me, and I wanted to work on that Web site too. Knowing that we all had things to say about these matters, we conceived of the project originally as something that would be written and put together by a collective (either our present one or maybe another one that would come out of this), and we even broadcast invitations for other people to join the project. But as things turned out, Delfina and I were the only ones who really did writing and editing for this project, and that’s how we became the co-authors of the future book.

I should add, though, that some people did some very helpful writing about our project… In particular, we got a lot of support from people in Indymedia, some of which surprised me.

I guess I wasn’t too surprised—though I was grateful—about the support we had gotten from one old organizing partner, Priya Reddy. I had already talked to Priya about these sorts of issues because she also had felt very hurt by her own recent experiences along these lines, dealing with her own banning, etc. But I was a little more surprised when other people, from IMCs out west, etc., took to our project too and spread the word even more. By the way, I’m aware that Indymedia is the only group I’m mentioning by name as a source of some people’s troubles, and I’m sorry, but I don’t see a way to get around that while telling this tale. On the other hand, fortunately, I can also name Indymedia as a group that did a lot of good for us, especially in the beginning.

DV: I now see my experience, in some respects, as that of a patsy. I was blindsided by the maneuverings and cruelty I encountered, and also by my own anger and exasperation. The silver lining is that as a relative outsider, who was never entirely accepted, I had a clearer vantage point from which to describe what I saw.

Q: Do you personally seek to create or belong to collectives? Did the experiences that led to this book not burn you out completely on the whole interpersonal world of collectives, or do you see them as essential nuclei of social organization?

RS: OK, I think I partially answered this in my long response to question #1. Yes, I sought to create collectives, and I belonged to them—quite a few of them, from our own little Staten Island collective to bookstore collectives, writing collectives and, of course, collectives that were part of larger political groups.

Like many people, I had become interested in collectives through reading about them in political world history. I had been very interested in the collectives of the Spanish Revolution. In terms of more recent history, in the late ’90s, I started reading a bunch about the collectives (and workers’ coops) in one “quiet revolution” that advanced an egalitarian social-democratic movement in Kerala, India. And, of course, there were lots of other examples I had read about… So, the idea of the collective was always important to me politically…

But I’ve grown a bit more pessimistic about political collectives or radical political groups in general who form based on a big political idea without the context of a major movement and without any practical application in mind either. For one thing, my experiences have caused me to lower my expectations about whether groups will actually practice what they preach (to use an old cliche). I think a lot of this has to do with the overall social environment. It is just very difficult, in the present environment, to form a small group based on truly egalitarian principles and keep it functioning according to those principles. In general, I think we’re not all going to have the opportunity to do most things in a radically different way until we somehow manage to start a real, sweeping social revolution.

DV: I’m not an expert on collectives. What I wrote (I won’t speak for Richard, though I’m guessing he would say the same) was based on first-hand observations. Whatever value it may have for others is as a description of what can go wrong, hopefully analyzed with some insight and laid out with some clarity so it can be reflected on out in the open.

My opinion on collectives is that they may not be perfect, but they are probably the best structure out there for inclusion and fairness, and I think they are worth trying to strengthen, of course, or I wouldn’t have taken up this project. Personally, I haven’t been in any collectives recently, but that has more to do with my own orneriness and shyness (as well as with my health, which doesn’t allow me to get out much) than a lack of faith in the usefulness of collectives. (more…)

Posted on January 21st, 2010 in AK Authors!

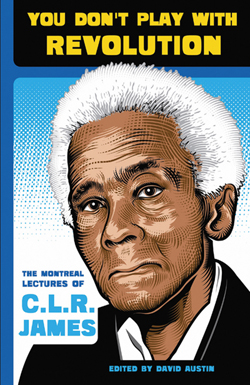

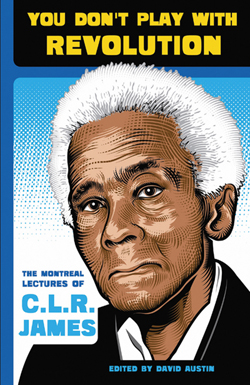

David Austin, author of You Don’t Play with Revolution: The Montreal Lectures of CLR James, gave a really great, hour-long interview on KPFA’s “Against the Grain” last week. I highly recommend listening to it. The show’s host, Sasha Lilley, did a nice job of asking good questions and then letting David answer at length, with his usual measured eloquence. Folks into CLR James and/or the politics of the Caribbean and/or the revolutionary African diaspora—or simply the history of the twentieth-century Left—will learn a lot. Personally, I don’t agree with CLR’s interpretation of Lenin, but David does a nice job of explaining it, of laying out the logic behind it, and explaining why the questions Lenin raised (in this case, about trade unions in Russia) matter.

David Austin, author of You Don’t Play with Revolution: The Montreal Lectures of CLR James, gave a really great, hour-long interview on KPFA’s “Against the Grain” last week. I highly recommend listening to it. The show’s host, Sasha Lilley, did a nice job of asking good questions and then letting David answer at length, with his usual measured eloquence. Folks into CLR James and/or the politics of the Caribbean and/or the revolutionary African diaspora—or simply the history of the twentieth-century Left—will learn a lot. Personally, I don’t agree with CLR’s interpretation of Lenin, but David does a nice job of explaining it, of laying out the logic behind it, and explaining why the questions Lenin raised (in this case, about trade unions in Russia) matter.

Anyway, click here to listen.

Posted on January 20th, 2010 in Store Profiles

I’m pleased to report that on my recent trip out east to visit my family, I was finally able to stop by The Big Idea Bookstore in Pittsburgh. I’d tried to go by and check it out last time I was in town, this fall —but it just didn’t work out then, possibly because the entire city of Pittsburgh seemed to still be in recovery after having been invaded by so many riot cops the previous weekend.

I’m pleased to report that on my recent trip out east to visit my family, I was finally able to stop by The Big Idea Bookstore in Pittsburgh. I’d tried to go by and check it out last time I was in town, this fall —but it just didn’t work out then, possibly because the entire city of Pittsburgh seemed to still be in recovery after having been invaded by so many riot cops the previous weekend.

Anyhow, this time I got a chance to check out the Big Idea as well as meet a few of the collective members. They are swell people and they’ve got a good thing going on there, so I decided to write them up as our latest store profile! Two collective members, Hannah and Dave, were kind enough to answer some questions for me…

AK: Can you tell me when and how the Big Idea got started, and how you got involved?

Dave: The Big Idea started on February 14, 2001… I’ve only been involved for a little over a year, having seen the storefront on my way home from work one night. I checked it out and started volunteering shortly thereafter.

Hannah: The Big Idea started—long before my time—at [another] location, in Wilkinsburg (a different part of Pittsburgh). It was part of an umbrella group called The Multi-tool, which included the bookstore, a show space called The Mr. Roboto Project, and a free bicycle resource called Free Ride. The other organizations still exist, but The Big Idea moved in early 2004 to its current Bloomfield location. I started volunteering in January 2009. I think I originally learned about the store some time before that, when trying to figure out where I could get a copy of Maximum Rocknroll in Pittsburgh.

AK: What would you say is the main mission of the Big Idea collective? Do you see yourselves primarily as a bookstore, or does your space serve other purposes as well?

Dave: We’re a small space, so at this point we’re mostly into selling radical books and zines. We’re looking to moving to a larger space so that we can focus on events and making space available to other groups.

Hannah: We would be ecstatic to open our space to a multiplicity of purposes, but our current, tiny location scarcely allows room for more than three people to stand around at once…. We hope to someday buy our own building, which would necessarily be bigger (and just about anything would fall into that category). With more room, we would strive to become a community space as much as a bookstore.

AK: How do you choose the books you carry? What do people come in looking for?

Hannah: We admittedly order most of our books from AK (what up, AK!), although we also carry the works of many other publishers. Our buying process is collective: any collective member is welcome to flip through catalogues and choose which books they would like to order. We tend to reorder books that sell well. Right now, some of our most popular books are about sustainability—like The Urban Homestead and Toolbox for Sustainable Urban Living.

Dave: We all go through the catalogs, if we’re interested in participating in the order, and make a list of what we’d like to carry. Then as a collective we go over the list and pare it down—usually based on what we can afford that order, what has sold well in the past, and what we think is just worth carrying. People come in looking for all kinds of things: zines, used books, the latest New York Times bestselling political outrage book (which we never have)…

AK: How is your collective structured? How many people are involved at any given time? How many people does it take to keep the store open?

Dave: We’re a “flat” collective. The only “authority” roles are the coordinators who make sure essential shit gets done (paying bills, communicating info, etc.). All decision making is collective and consensus based. I couldn’t say how many people it takes to keep the store open. Right now we have about a dozen volunteers, including some new folks, and we seem to be doing all right.

Hannah: The level of involvement in the collective is self-selecting. Volunteers can choose to simply cover shifts, or they can choose to participate more by taking on coordinator positions. We use loose consensus to make decisions, and we are usually able to discuss issues casually as a group, as there are always less than 10 people at any given meeting. Most of the volunteers we work with are pretty reasonable people, as well. The particularly unreasonable ones tend to self-select out.

AK: From an outside perspective, it seems like there’s been a lot of anarchist/radical folks traveling and moving to Pittsburgh in recent years. Is that a fair assessment? How has that affected the city and your project?

Hannah: The influx of radicals is, of course, a double-edged sword. On the one edge, more radicals means more patrons and more volunteers. On the other edge, they have tended to be a transient bunch without the commitment levels required for running a bookstore. Many times, newbies to Pittsburgh will find out about the store, decide they want to volunteer, tell us all the ways that they are going to improve space, and then disappear forever.

Until this past year, Pittsburgh had long been an isolated city—missing from the maps of many travelers, as well as movers and shakers. But 2009 turned the spotlight onto Pittsburgh brightly and hotly: The city hosted conferences for liberal bloggers, union organizers, and Crimethinc. kids alike. And the international attention was still yet to come in September with the G-20 spectacle and debacle. Beyond all this, the mainstream media have begun to tout Pittsburgh as a “green” city success story—a statement that is certainly up for debate.

All this attention has made more than a few people uneasy. With Pittsburgh becoming such a popular place for anarchists to relocate, some wonder if they will really stay or if they might soon move on to the next hip city. This place has always been a retirement town for old punks who want to buy houses. But could it become a type of Bay Area soon—that is, a place that everyone has lived once but where no one stays forever? Within the next year, I think we will see whether or not our city’s popularity will last.

AK: What have been the greatest successes or achievements of your project?

Dave: Our biggest achievement is just staying open. We’ve had some rough months this past year but have really pulled together as a collective to stay open by putting more hours to see that the store maintains regular business hours. We also had a fundraiser in December that was a whopping success that we hope to repeat in spring or summer.

AK: Do you have any advice for other folks out there trying to start up their own infoshops or distros?

Dave: I, as all the current volunteers, inherited the infoshop from the founders who have long since moved on the other projects. [So] perhaps the only advice I can offer is to try to not take on too much as individuals and always bring in new blood so that the infoshop’s operation doesn’t rely on a small core of people. That way, as people naturally come and go, the infoshop remains a fresh and vital project.

Howard Zinn, the Boston University historian and political activist who was an early opponent of US involvement in Vietnam and a leading faculty critic of BU president John Silber, died of a heart attack today in Santa Monica, Calif, where he was traveling, his family said. He was 87.

Howard Zinn, the Boston University historian and political activist who was an early opponent of US involvement in Vietnam and a leading faculty critic of BU president John Silber, died of a heart attack today in Santa Monica, Calif, where he was traveling, his family said. He was 87. Oh hey! Ashley here, the other half of your friendly AK Press shipping and receiving department. You heard from my counterpart Macio a little while ago, so I guess now it’s my turn…

Oh hey! Ashley here, the other half of your friendly AK Press shipping and receiving department. You heard from my counterpart Macio a little while ago, so I guess now it’s my turn…

I’m pleased to report that on my recent trip out east to visit my family, I was finally able to stop by

I’m pleased to report that on my recent trip out east to visit my family, I was finally able to stop by